Sovereignty can mean different things to different people, but to those of us in the space and defence domain, sovereignty is about resilience.

Resilience is our ability to bounce back from adverse situations or conditions. It’s easy to see how multiple dams could improve the resilience of our water supplies for example, and how an integrated train and bus service would result in a more resilient city transport system.

Resilience is not necessarily about instituting a direct replacement. It is more about creating a system that allows for the continuation of a service, organisation or way of life.

The Covid-19 pandemic highlighted the importance of resilience. During the pandemic, we saw nations put the needs of their citizens first – be it for masks, vaccines, Covid-19 tests or respirators – over that of their allies and trading partners. Whilst understandable, it showed that we cannot fully rely on others for critical supplies and technologies, especially in times of great need.

Two years of closed borders and Covid lockdowns have also disrupted global supply chains across the board, from aluminium sheets to semiconductor chips.

For a rocket and satellite manufacturer requiring thousands of parts, some of which are still delayed by over 12 months, a stronger onshore or local supply chain would have clearly strengthened and accelerated our overall development and manufacturing efforts in Australia.

The war in Ukraine added further impetus to the issue of sovereignty and resilience. The North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) has described Russia and China as threats to world security.

As we know, Russia recently invaded a neighbour without provocation; Ukraine ran low on most ammunition within weeks, and it is now reliant on NATO nations for resupply. It is fortunate for Ukraine that its allies were not under attack at the same time.

And what about climate change? How can we better prepare for, and recover from, increasingly severe floods, fires and storms, in the years and decades ahead? There are fears that climate change could impact food production and energy supplies, among other things, and lead to greater geopolitical tension and conflict.

These examples point to the need for ‘sovereign primes’ in key industries like defence and space – the latter has been listed as a critical technology in the national interest, and a Sovereign Industry Capability Priority for defence.

The rise of Australian Primes

I believe it’s very important for Australia to nurture and grow aerospace primes that are Australian-owned and operated.

In the context of space and defence, a ‘prime’ is a company that has the overall program responsibility for delivering a major project to the customer.

Most primes in Australia today are foreign-owned companies with Australian branches or subsidiaries.

For a variety of reasons, including home country requirements to buy local, regulations such as US International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR), a preference for trusted suppliers or access to an existing supply chain, applicable tariffs and duties, among others, foreign-owned primes are incentivised to buy components, and indeed, to manufacture the final products or vehicles in their home country.

With foreign primes, intellectual property (IP) is often held and controlled by the parent company, requiring the employment of employees from or in the home country, and ultimately the production of components and products offshore. Profits also tend to flow onto the home head office or to a tax haven such as Ireland.

What Australia is ready for today is its own sovereign primes. These are companies that are Australian-owned and controlled and are leading major programs – particularly of national interest.

These companies are sourcing from local suppliers, hiring and upskilling local talent and working with partners to develop meaningful capability in-country. They are increasing the depth and resilience of local supply chains, strengthening the economy, creating and keeping new IP and profits in Australia and protecting our nation from adverse shocks or events.

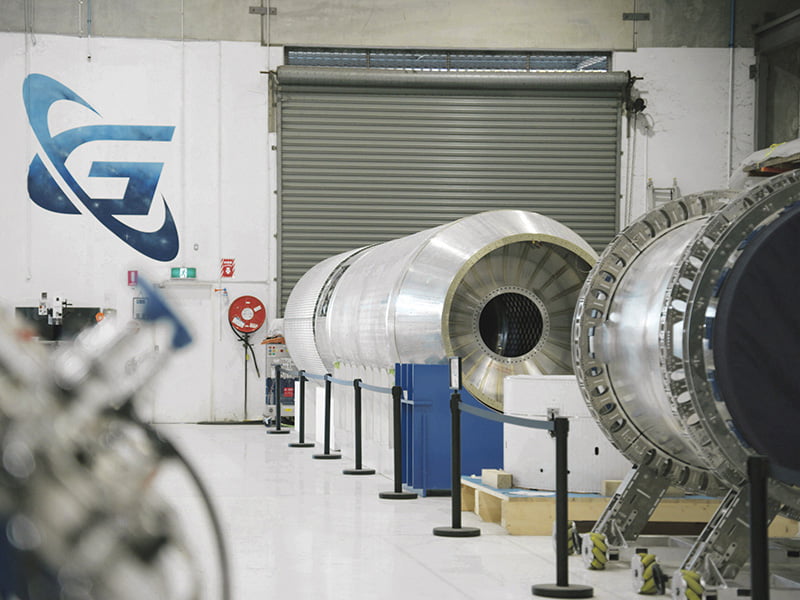

The good news is that we are seeing the emergence of Australian-owned companies, like Gilmour Space Technologies, that are working on developing significant new sovereign capability for space and defence.

The role of government

How can the government help to grow sovereign primes in these key industries?

Firstly, stop parcelling out funding into many tiny amounts, especially without due consideration to relative merit, and start picking winners.

Small government grants don’t build meaningful capability.

Most technology projects require $10 million to $100 million, upwards of 50 employees and at least two years of development to produce a capable prototype.

Until very recently, the average Defence Innovation Hub, Sovereign Industrial Capability Priority, Australian Space Agency and Department of Industry grants were under $1 million – just enough to hire five good engineers for two years, but with no money left over for parts, machines or rent.

Giving out small grants is a bit like turning on a life support system for 12 hours and hoping for a quick recovery after you turn it off.

The government may see investors coming in to fill the gap; but investors prefer to invest in technologies that are further down the development path. At Gilmour Space, we had to test multiple engines and launch a suborbital rocket before we closed our first round of funding.

Rather than supporting future champions, small grants help to create zombie companies that are barely surviving or pushing the technology forward. The lack of certainty in follow-on tranches and significant delays in disbursements have also seen the exit of many good companies.

Why pick winners

SpaceX – whose early launch attempts were funded by various US agencies, and which received a billion-dollar NASA contract after its first successful launch – is a great success story for why governments should pick winners.

OHB in Germany is another. As a small satellite company with under 200 employees, it beat some very large and established primes to win a multi-billion-dollar contract to develop a constellation of Global Positioning System satellites for Europe. OHB is now one of the largest space companies in the world.

An Australian example could be CEA Technologies, which was picked by then-Defence Minister Christopher Pyne for a large defence radar systems contract and is now a world-class player in this technology.

Picking winners works because companies that have developed key technologies and markets in their early stages are already on track to succeed, and they are likely at or near a tipping point to accelerate from government funding or contracts.

Good execution will be key

The $15 billion National Reconstruction Fund proposed by the new Labor government to support advanced technologies and critical technologies is a good start for Australia, provided it is well executed.

Without knowing the details, a one-third split between government grants, government financing, and private and venture-capital investment could be an effective way to disperse the funds.

Venture capitalists (VCs) are savvy investors who have ‘seen the movie’ hundreds of times before. They generally invest in only one out of 100-plus startups they see and could be incentivised to participate if the government is providing the bulk of the funding through grants and loans.

VCs tend to stick with the company as it grows, providing great advice to founders as well as follow-on funding to companies that show good progress.

The government would benefit from this strategy when the new employees pay income tax, and when the companies themselves pay corporate tax, Goods and Services Tax, and payroll tax. The government also gets half of their investment back, with interest, as the company pays back its debt.

From the company’s perspective, a one-third debt ratio should be manageable on the balance sheet whilst still allowing them to repay the loan. Meaningful government support could help promising companies raise further private funding for their research and development, which tends to be headcount heavy for the space and defence industries.

Sovereign prime benefits

Say the government buys a launch vehicle (or rocket) that’s made in Australia for $10 million. At least 50 per cent of the cost is employee salaries, on which the federal government collects about 25 per cent or $1.25 million in income tax.

Our state government gets another $250,000 in payroll tax, and GST on the sale will be $1 million. Assuming a $2 million profit and 25 per cent corporate tax rate, or $500,000, adds to $3 million in total taxes paid to state and federal governments on a $10 million sale of an Australian rocket.

Beyond taxes, every dollar the government spends on an Australian-made product will multiply through the economy many times more than for a foreign product – like through the supply chain, and from employees here spending their salaries on Australian goods and services.

Resilient supply chains

Australian primes are driven to build capability through a local supply chain. For example, our company has connections with over 300 Australian suppliers for the Eris launch vehicle and G-class satellite platform – for the fuel and oxidiser tanks, electronic components, harnessing equipment, rocket engine components, fuel, gases, pressure vessels and ground support equipment.

Besides pouring tens of millions of dollars into our supply chain, our development spending and brand name have allowed suppliers to enter the space industry with new products and services that could be sold or exported to other Australian and international space companies.

When our Eris rocket launches to orbit, 300 Australian companies will have ‘space-qualified’ their products for the international market.

Resilient workforce

Australian primes can help to build a more resilient workforce in critical technologies. Workforce development usually starts with a few larger companies employing and training the first 100 employees, who inevitably move out into the greater industry.

Unsurprisingly, many space entrepreneurs in the US have come from SpaceX, and many of the software startups in Silicon Valley have come from Microsoft, Google and Oracle. The same seeding will naturally occur with Australian primes in the space and defence sectors.

What sovereign space products can we make in Australia?

Australian companies are already making space products in Australia. Gilmour Space, for one, is developing and manufacturing Australian-made orbital-class rockets capable of sending small satellites into low earth orbits.

Broadly speaking, this includes the manufacture of aluminium alloy fuel and oxidiser tanks, composite pressure vessels, composite payload fairings and nosecones, fuel and oxidiser valves, additively manufactured rocket motors and motor components, ablative materials that work in extremely high temperatures, rocket guidance, navigation and control software, optical tracking systems, radar tracking systems, radio frequency and electronic warfare systems and more.

I am not an expert in all defence and space technologies, but from my perspective, Australia should most certainly have its own capability in the manufacture and launch of sovereign rockets that will guarantee Australia’s access to space.

A senior member of the Australian Space Agency recently said: “There is one way to access space, and that is to launch. If we’re manufacturing here, and we are designing and developing here, then we can only go so far if we are not launching here.”

We should be making our own small satellites (up to 500 kilograms) to ensure Australia’s continued access to Intelligence Surveillance, Reconnaissance (ISR) data and communications for our defence; as well as resource management, fire detection and disaster recovery capability on the civil side.

We also need the ability to produce short-, medium and long-range missiles. Long-range strike can deter aggressive forces from considering or coming close to our shores. If Ukraine had long-range strike missiles ready before the first Russians tanks crossed the border, the war may never have started.

Now is the time

The industry is already moving forward in the production of major systems and components in space and defence.

Now is the right time for the Australian government to focus more energy and spending on the Australian-owned companies that will become sovereign primes.

It’s time to change the government’s posture on risk, which still sees Australian products and companies as risky and incapable of developing more than small parts for foreign primes.

Wholesale changes in the procurement process will be needed for innovation to proceed rapidly in defence. Ironically, it seems harder to get a $1 million deal from Defence than a $1 billion deal.

It’s time for Australia to spend more on research and development (R&D) – start by matching the US’s budget as a percentage of total defence spending and then create systems that allow this money to be funnelled quickly into the Australian industry.

In my company, I give spending authority to all my direct reports and their one-downs, which allows them to make quick decisions on purchases.

In the same way, Defence could give all one-star-equivalent officers involved in technology projects an annual budget of, say, $30 million to spend on R&D and two-star-equivalent officers a budget of $100 million.

There should be a new defence innovation fund with a minimum spend of $10 million dollars instead of a cap of $8 million. This level of investment would allow ‘decent’ capability projects to get going. The chief of each force could do quarterly reviews to ensure the projects are on track, joined by the Secretary or Defence and Chief of Defence Force.

All major space and defence nations have a robust domestic procurement policy and development programs that go into the billions per major capability. Now is the time for Australia to step up and take its place as a competitive and vibrant space and defence local player.

Space and Defence technologies take time to develop and mature. The longer the government takes in making the first bold decision, the longer it will take to grow the sovereign capabilities and Australian primes we need to ensure a more resilient nation.

Let us start here today.

Adam Gilmour is the CEO and Co-founder of Queensland-based Gilmour Space Technologies, an Australian-owned rocket and satellite company that will launch satellites into low earth orbits from as early as 2022. A lifelong space fan, Adam believes that rockets can be made smaller, cheaper, faster, and that the New Space industry, and Australia, would benefit greatly from having more dedicated access to space.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.