Not every foreign business in China need fear the cold winds of data regulation, but multinationals that capitalise on the PRC’s vast market and R&D capacity can expect to shiver.

Big Tech and big finance have shared the shock of Didi Chuxing’s relegation to bit-player status, despite drawing investors to its IPO. The erstwhile ride-hailing giant, which had Uber bumped out of the People’s Republic of China Sumo-wrestler style, is the latest victim in a Beijing crackdown on its own tech champions.

Yet something deeper is flagged here. Didi drew the regulators’ ire not simply as a rogue tech company, but as owner of a vast trove of sensitive and strategic data.

In today’s ‘decoupling’ world’, global firms operating in China will have to set up (at least) two separate data systems: one to remain onshore for their PRC operations and one for the rest of the world.

Regulations will come sector by sector. Activity in relation to automobiles and health show others sectors what is to come.

‘Splinternet’: two data regimes

In recent years, international industrial interests, above all those that are research and development intensive, have spoken of building at least two separate supply chains and R&D bases.

Beijing’s emerging cross-border data regime provides a microcosm of its response to ‘decoupling’ from global supply chains.

Fully localise operations. This is the takeaway for multinational corporations (MNCs) – not least giants like Apple and Tesla – looking to capitalise on PRC talent and data troves.

Little will change for firms that see China as only a manufacturing base or minor market. Preferential treatment may be offered at favoured sites like Hainan, but don’t count on them for blanket exemptions.

Four years and a trade war after the Cybersecurity Law, Beijing is set on clarifying the rules.

Work on criteria to sort out types, thresholds and sensitivity of important data – mainly national security, the public interest, economic order and/or state operations – is led by the Cyberspace Administration (CAC) and Ministry of Public Security (MPS).

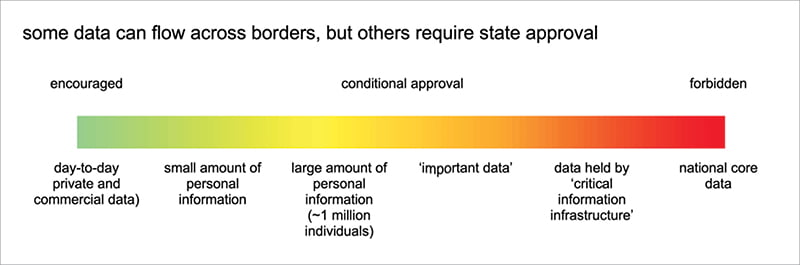

Normal data – including personal information – vital to business and trade can flow across borders. But as stipulated in the recent labyrinthine laws on cybersecurity and data security (as well as that proposed for personal information protection) data of strategic importance may not be transferred without state approval.

Autos and health: test cases

Defining the data regimes results from intense behind-the-scenes negotiations among stakeholders. The broad definition of terms, processes and categories leaves room for tailoring to sectorial and even local needs.

Regulatory design will not rest with the security establishment, privacy advocates or protectionist officials. Sectors or regions whose data localisation rules deter foreign investment may win more lenient terms from central agencies and/or local governments. Greater leniency is also mooted for SMEs, sensitive to high compliance costs.

Regulatory scrutiny in the pivotal auto sector flags changes likely to become system-wide. Industry regulators, in tandem with the CAC, responded to Tesla’s opaque and controversial data collection practices with data security criteria.

Rules are tailored to the sector: personal data collected by automakers, ride-hailing services, repair shops and insurance firms may not be sent overseas without CAC approval; non-personal data deemed of national importance, for example the flow of traffic in military and defence sites, or high-precision map data, must also stay in China.

Tesla, BMW and Daimler have now announced plans to store all consumer data locally. In future, one-off market entry requirements may apply to smart vehicles.

Such efforts are mirrored in the healthcare sector, where health regulators have formulated data regimes.

Population and healthcare data are subject to stricter rules than those prescribed by the new laws: most data, personal or not, must remain in-country.

Transfer of human genetic data is strictly prohibited and separately regulated. Similar to the auto sector, smart medical equipment is governed by standalone rules.

Tight regulations, loose enforcement

Restrictions on cross-border data transfer are unlikely to be rigidly enforced, given that export control rules have never been carried out with much heft. Limited capacity at the centre is one reason, not unlike General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) enforcement in Europe; fears of stifling foreign R&D investment is another.

Big firms holding personal information in bulk, or whose information technology footprints have a significant impact on the domestic economy, are the bogeymen. They will be (or, as in the cases of Apple and Tesla, already are) the first to be asked by regulators to store personal information and important data locally.

Sectors mooted for more stringent treatment are those in which all parties converge on the need to localise storage, for example healthcare and genetic resources or, even more strategically, smart vehicles and voice recognition algorithms.

International actors should review their China operations and associated data flows in the light of these trends and their likely regulatory repercussions.

Once they are embroiled in controversy, or when Beijing’s bristles at some geopolitical event, it will be too late.

Philippa Jones is managing director at China Policy and comes from a background in foreign policy and trade policy. Chim Lee is lead SciTech analyst at China Policy.

China Policy tracks and maps agendas, people and agencies shaping policy development and execution. Unrivalled in its cross-sectorial breadth and depth, it delivers insight into the PRC, its successes and failures, its systemic pathways and breaking stories.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.