Here we go again. On December 3, Minister Stuart Robert unveiled the latest Government Digital Strategy (GDS) at a gathering of the Australian Information Industry Association (AIIA) in Canberra.

This strategy has as its vision that by 2025, Australia will be one of the top three digital governments in the world.

That’s right. A vision that’s all about a leader board ranking. A beauty contest.

I have written about government digital strategies around the world for 25 years, so I’m always keen to dig in.

Goal number one of the new Government Digital Strategy is that “all government services are available digitally by 2025”.

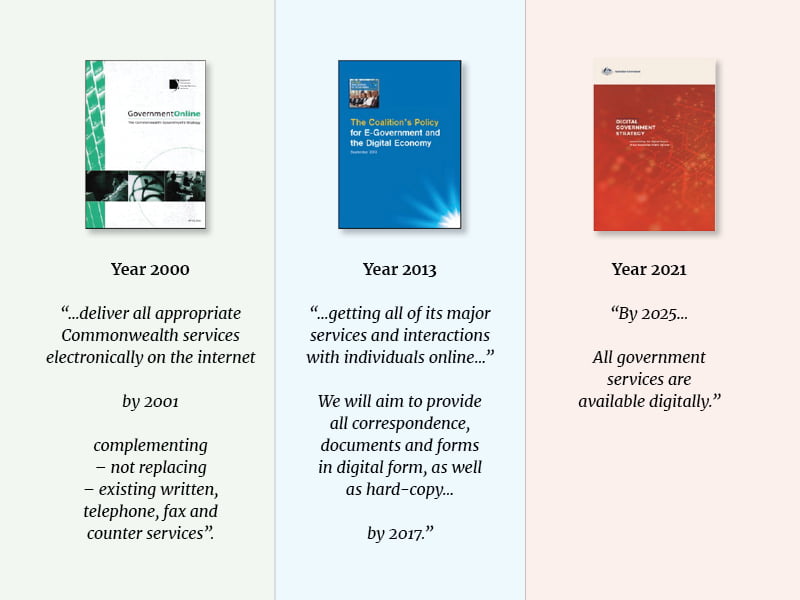

What makes this goal utterly unexciting, is that it is almost verbatim from the year 2000 “Government Online Strategy”, and the year 2013 policy for “E-Government and the Digital Economy”.

The paradigm has not changed in 21 years. The targets are disappearing further into the future with withering ambition.

During this same 21-year period, the architecture of the internet has changed and continues to change, and a new warfare vector of cyber has emerged. And while there is much talk in the strategy about things changing with COVID, the strategy itself has not changed.

Think about this in terms of ambition. It took less than 10 years to put a man on the moon in the late 1960s when the technology to do so didn’t even exist.

And over the past 21 years, the international space station has been continuously occupied. But it seems that for the past 21 years, Australia has been struggling to put forms online, or get rid of them.

And while forms online and services online has remained the fixation of sclerotic digital strategies for two decades, consuming literally billions of dollars of taxpayer dollars, tens of thousands of forms continue to metastasize across government.

And the reason why this is happening notwithstanding the staggering investments, is that forms online, and beauty contests do not make a strategy. There is no benchmark or inventory to quantify the magnitude of the problem – including economic impact.

It is not actually possible to search on Australia.gov.au to find out how many Australian government forms there are. To get a sense of what’s happening in other jurisdictions, a search for ‘forms’ on the UK Government’s gov.uk website returns 77,504 results.

A search on Services Australia results in an extraordinary 126 pages with nested lists of forms. In this day and age, there is even an option to place an order for a form, including by fax. Think about that.

The Business Entry Point (www.business.gov.au) facilitates access to some 20,000 business forms and licences across the three levels of government in Australia. I ran the Business Entry Point for five years and I know this landscape well.

A search for forms on the NDIS returns 131 results. Home Affairs returns an extraordinary 3480 results, and I gave up searching when I got to 220 web pages of listed forms.

A search for forms on the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment returns 2759 results, many in PDF and word.

Unfortunately the Department of Veterans Affairs website could not be searched at all but digging through identifies a whopping 289 forms. In my opinion and as a veteran family, the DVA website is the worst of all government websites.

So we don’t know the magnitude of the challenge that is “all services available digitally”.

Perhaps the biggest gap in the strategy is that it fails to acknowledge that the majority of Australians interact online through audio-visual means (eg gaming platforms, virtual environments).

And so with this re-hashed 21-year-old strategy, we can all expect the horror of forms to be around for another 21 years. That is a truly disturbing prospect.

Now to the leader board beauty contest.

Cherry picking rankings in any field is problematic because context is missing. And this latest Government Digital Strategy is completely devoid of context.

When we add the context of broadband speeds, global digital competitiveness, and the Global Cybersecurity Index, the pinnacle of the new Government Digital Strategy – the beauty contest – is an illusion.

From a cyber security perspective, Australia ranked 12 on the Global Cybersecurity Index 2020, just behind Turkey. So perhaps in this field, Estonia at number three might be an appropriate aspirational competitor.

But context is key, and what’s happening – or not happening – within Australia itself is perhaps the real call to action. Not the beauty contest with Estonia.

In the latest cyber resilience review by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO), the Prime Minister’s department and the Attorney General’s department were among the agencies that failed the cyber security audit, with the auditor finding them not cyber resilient and “vulnerable” to attack.

But it’s worse than failing. The audit revealed that PM&C and AGD incorrectly self-assessed as fully compliant.

The article, “Australia’s most important government agencies refuse to secure their IT systems”, considered that the ANAO finding elevated cybersecurity from “a long-running public service debacle into open defiance by bureaucrats.”

Turning to global digital competitiveness rankings, Australia is now lagging behind much of the rest of the world, according to the CEDA chief executive Melinda Cilento.

And whilst Australia has fallen to number 20 in world digital competitiveness rankings, Estonia has also slumped to number 25.

Similarly for mean fixed broadband speed across OECD countries, Australia ranks 32 while Estonia ranks 31. Globally for mean broadband speed, Australia ranks 59 – between Vietnam and Croatia – and Estonia ranks 56.

So, it’s intriguing that in this Government Digital Strategy, Australia looks to Estonia. We now want to be a leader in digital government, like Estonia. Yet for decades we modelled ourselves on the UK digital efforts and look at the results.

In 2014, I co-wrote a paper with Dr Jerry Fishenden from the UK “A Tale of Two Countries: the Digital Disruption of Government” which compared the digital transformation efforts of the UK and Australia over twenty years – with confronting findings.

“…an estimated US$3 trillion was spent during the first decade of the 21st century on government information systems. Yet 60 per cent to 80 per cent of ‘e-government’ projects have failed in some way, leading to “a massive wastage of financial, human and political resources, and an inability to deliver the potential benefits of e-government to its beneficiaries”.

Australia is a massive patch work of cultures, economies, and vast landmass. And we need a forward leaning digital strategy that is contextual to our unique circumstances: not a decades old re-hash bolted on from elsewhere.

Perhaps in some specific instances or scenarios, insights from Estonia or the UK might be applicable.

But it is definitely not the case universally, especially for regional and remote Australia where our own innovations or even adaptations from other environments might be better suited.

For example, innovations from Africa, where telco’s offer e-payments, e-health, and renewable energy as a basket of services. And this is how government digital services should be delivered: in context.

(By the way, have you ever wondered why Africa – and even China – don’t have the massive government forms problem? That’s another story, but completely relevant.)

This beauty contest of a strategy is chock full of marketing puffery. A veritable bingo board of Silicon Valley-esque descriptors: unprecedented, exponential, rethinks, re-imaginings, momentum, accelerate, urgency and cutting-edge technology.

But what is missing from this strategy, is any mention of diversity, inclusion, accessibility, algorithms, lawfulness, or ethics.

This is quite extraordinary given that these have been critical factors in high profile digital disasters: RoboDebt; CovidSafe App; and the highly controversial NDIS work on algorithms and ‘roboplans’ that caused a revolt by all the states and hundreds of thousands of Australians.

And ironically, with the “excessive use of consultants within the APS and the relationship of dependence that has formed”, there is an open question as to how many consultants helped craft a strategy which continues the handwringing over the public sector skills deficit.

Perhaps the next government digital strategy should be created by feeding all the digital government strategies worldwide into an AI – with all the essential context – and see what insights it comes up with. It could be more effective, and it will certainly be much cheaper.

Marie Johnson was the Chief Technology Architect of the Health and Human Services Access Card program; formerly Microsoft World Wide Executive Director Public Services and eGovernment; and former Head of the NDIS Technology Authority. Marie is an inaugural member of the ANU Cyber Institute Advisory Board.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.

Thanks Marie. The APS “skills deficit” may not be what we imagine. In this era of chequebook bureaucracy the APS can’t even work out what to buy. It can’t use words correctly and calls things by the wrong names. It’s heavy into jargon and malapropisms. It’s no wonder that it asks for the wrong things, buys the wrong things, increases the contract price by 300% (in the dark of night, no new tender needed guys, nothing to see here, wink) and still ends up with a failure – “fail fast”, remember that slogan, thanks Paul Shetler. These days big-fee consultants write their own work orders, which their on-site contractors can process and recommend for payment. If they could sign the cheques or log in to the department’s bank account I’m sure they would do that too. There’s no point in talking about APS “skills” unless you like talking about dodos and dinosaurs, which are also extinct. The Public Service Academy could teach a core APS skill – how to be sucked in by marketing jagon and Sydney suits. Not happening. APSA is ranting about “integrity”. But isn’t integrity the opposite of hypocrisy ?

Who searches for “forms” in a government website? WTF

Spot on. Various senior bureaucrats and ministers have been spruiking the same messages for over 15 years, but any examination of what they have actually done is described in this insightful article. The aggregations of forms loosely linked by letterheads cannot be classed as a digital engagement strategy and simultaneously isolates citizens with limited access or knowledge of the technology platforms that are abysmally deployed. Total failure of senior public servants advising Technology illiterate ministers, regardless of party affiliation.

Reaping the tawdry harvest of dependence on multinational consultants and their imitators

With Stuart Roberts at the helm, it’s almost guaranteed nothing will change and may indeed devolve further. Has he achieved anything positive (for anyone besides himself) in any of his portfolios?

Thanks Marie as always spot on and brutally honest with first person experience and data to back you up. The very concept of a digital strategy is obsolete. Technology is powerful and pervasive and so should be invisible. The strategy should be about delivering highly efficient government services to everyone, anywhere, anytime when needed and across all channels of delivery paid for as promised in various legislated government policies. The AIIA unfortunately is, despite what they say, controlled by the global suppliers of the failed systems you highlighted above.

I’ve been a big fan of emerging technology, I was the first employee in my organisation to use the Apple Macintosh desktop computer back in the mid 1980’s. I’ve kept up to date with new tech like Teams, Zoom etc even though I haven’t been employed for the past four years. I’ve been caring for my elderly parents for the past 12 months, my father paid all their bills in person at the local post office using cash he took from an ATM. They have no online banking setup, they can’t use a mobile phone and their laptop takes 20 minutes to start up and they only use that to read emails. They have no desire to learn or the capacity to use technology to do anything. It’s only now that I’m taking over their affairs that I am aware of how this generation is completely cut off from doing business with anyone if they can’t do it online. This situation is going to be a problem for all of us as we age. I’m in my mid 50’s and already I get totally frustrated with the design and technicality of many online applicaitons. Added to this are frequent outages of the internet due to unreliable electricity supply, storms or random breakdowns. It is also assumed that everyone can afford to purchase the technology required to engage and pay fees to keep it operating. I think we need to be very aware that whatever systems are developed in the future there will be a segment of society who will not be able to participate if funding is not provided for social support to help people navigate an increasingly technological world.

Sarah writes: “It is also assumed that everyone can afford to purchase the technology required to engage and pay fees to keep it operating.” Another and oft repeated reason why the digital space should become a public utility.

Absolutely, it’s not about getting forms online, it’s about understanding behaviours and thinking about what’s appropriate in these spaces. You can’t transfer old thinking to new formats. And yet….. Who are the people really behind these strategies, and what are their backgrounds?

There’s no mention of co-design, and as you say, nothing of substance.

And btw, if you follow the link from the media release:

“For more information on the Digital Government Strategy, please visit: http://www.dta.gov.au/digital-government-strategy”

you get:

“Sorry, this page isn’t working”