Malcolm Turnbull has delivered a sometimes gushing pro-China speech at the University of NSW in Sydney, just two days after Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi asked Julie Bishop during a 45-minute meeting in Singapore “to return bilateral relations to a healthy and stable development track”.

The address to educators and students was also surprisingly and eventually somewhat disturbingly tech-heavy in its content.

“You know, there are 1.2 million Australians of Chinese heritage, two of whom are Lucy’s and my grandchildren,” Mr Turnbull said

“It’s a very deep relationship, one of great opportunity and potential and it gets deeper and stronger all the time. Modern Australia is unimaginable without the talented and dynamic contribution of Australians of Chinese descent. They are a vital thread in the fabric of Australian society.”

He also praised Chinese investment initiatives.

“We look forward to working with China on the Belt and Road Initiative projects”, he said, referring to China’s aim to carve out new land and sea “silk roads” via countless billions of dollars in investment.

“Global infrastructure investment is a good example of where countries should work together, as we are for example in the Asia Development Bank and more recently in the Asia Infrastructure Development Bank.”

Frictions between Beijing and Canberra reached their peak following a Turnbull speech in late 2017 in which he said “our system as a whole had not grasped the nature and magnitude of the threat,” after ordering a top secret report into Chinese influence in 2016.

After that, his government signaled it would introduce legislation to curb direct foreign influence in Australian politics via lobbying and political donations.

A number of Australian Chinese businesspeople have been among Australia’s largest political donors in recent years.

In recent years, there have been serial revelations of clear evidence that China was wielding political influence in Australia via the 170,000 students it has on Australian campuses, and local Chinese language press and joint venture initiatives.

Experts have described this as long term campaign orchestrated by the ruling Communist Party’s opaque United Front Work Department, which looks after ‘overseas Chinese’, amongst other tasks.

Beijing has consistently and vehemently denied the claims, and described the legislation as “anti-China” and “Cold War thinking” and “hysterical paranoia”.

In response, China has flexed its trade muscles, slowing Australian wine exports and appearing to halt ministerial visits to the country. At least half a dozen senior Cabinet members usually visit Beijing each year, but so far in 2018, Trade Minister Steve Ciobo has been the only one let in to the country, and only to Shanghai.

More recently Ms Bishop and Mr Turnbull have both made efforts to turn around the biggest slump in relations in a decade, with a country Australia conducts 24 per cent of its two-way trade, worth $174 billion in 2016-2017 according to Trade Ministry figures.

Mr Turnbull devoted a chunk of his speech lauding the technology collaboration between two countries.

But strangely – given the government’s clear concerns about Chinese influence – he chose to highlight UNSW’s sometimes controversial technology collaborations with China.

“The University of New South Wales has embraced international partnerships and collaboration, particularly with China through the Torch program,” Mr Turnbull said.

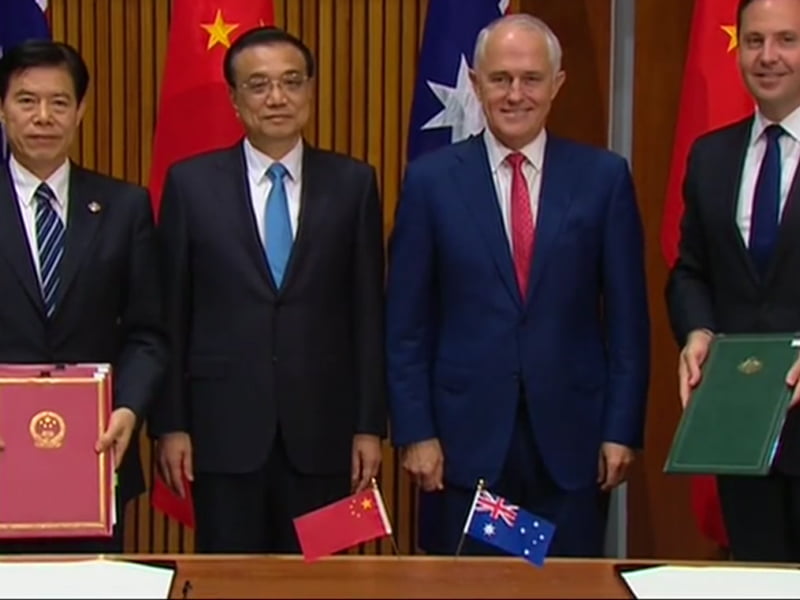

“Chinese Premier Li Keqiang and I were pleased to endorse the agreement for the precinct at the signing ceremony in the Great Hall of the People in 2016,” he said.

“Premier Li described it, and I quote, ‘as a shining beacon of bilateral cooperation in innovation and entrepreneurship’. And he’s right.”

Torch is a China-based research initiative which brings together domestic and foreign universities and technology companies. The precinct at UNSW is the first in another country.

Yet in September last year, The Guardian lined up a string of credible experts who cited fears of involvement by Chinese authorities as well as the People’s Liberation Army.

Critics believed that UNSW has little idea what it has bought into, and at times it seemed Mr Turnbull, too, had been poorly briefed, name checking one-time Australian Chinese solar panel billionaire Shi Zhengrong, whose company Suntech (although not him) went bankrupt in 2013.

Mr Turnbull then doubled down, claiming that the Chinese solar sector had been built by private enterprise, ignoring the billions of dollars of well-documented government subsidies that lead to a panel bubble as Beijing tried to steal a march on renewables technology, and the subsequent collapse. In April 2018, Beijing vowed (again) to curb subsides to the sector.

It’s worth noting, by the by, that much of Mr Turnbull’s tech-focus was on renewable energy.

“So this is a great partnership, critical at a time when the world is grappling with higher energy demands and costs. It helps us do more with less energy consumption and helps reduce global carbon dioxide emissions,” Mr Turnbull said.

“Because the intellectual property is Australian-owned, there are also significant economic benefits to us here in financial terms, Mr Turnbull said.

The timing of that focus is apposite, considering the government is trying to get Australian states to sign up to its National Energy Guarantee (NEG).

Still, despite all this bonhomie towards China, left hanging in the air was a particular thorny and increasingly immediate issue: whether Chinese telecommunications equipment maker Huawei Technologies be allowed to participate in any tenders by mobile networks for new 5G technology.

A decision by the government is looking close, as the first spectrum auctions for 5G were set by the Australian Media and Communications Authority for late November.

Huawei already provides 4G equipment to about 50 per cent of Australia’s combined mobile networks through contracts with Vodafone, SingTel Optus and TPG Telecom. Yet Huawei was blocked in 2012 from providing broadband equipment to the National Broadband Network, a move it – and its existing customers – have been lobbying the Turnbull government intensively to not have repeated for 5G.

“In our three decades as a company no evidence of any sort has been provided to justify these concerns by anyone ever,” Huawei’s Australian chairman John Lord told the National Press Club of Australia in June, adding that Britain and New Zealand had permitted 5G investments by Huawei.

“Nothing sinister has been found. No wrongdoing, no criminal action, no intent, no back door, no planted vulnerability and no magical kill switch,” he said.

China’s Ambassador to Australia Cheng Jingye and its Consul General Gu Xiaojie were both present at Mr Turnbull’s address, no doubt to make sure they cable back to Beijing the Australian government’s kind words.

Still, the lopsided nature of Mr Turnbull’s speech – as comprehensive as it was – makes it difficult to discern any overarching long-term strategy towards China.

At this stage it’s probably fair to brand this as a ‘Bandaid’ address, one that will be ripped off hard by Beijing if Huawei gets the thumbs down.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.