Whether wages are keeping up with the cost of living is shaping as one of the key election issues. Unfortunately, neither party demonstrates an understanding of the link between wages, productivity and innovation.

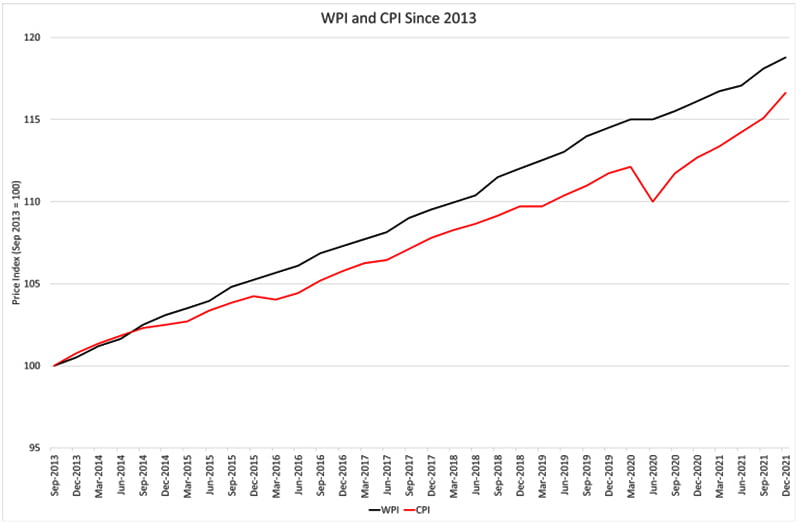

The issue has been a feature of political debate over recent months, and it has increased since the Budget. As with many such things, it depends on what period we choose to measure the changes. If we consider how both the Wage Price Index (WPI) and the Consumer Price Index (CPI) have changed since the election of the LNP Government in 2013, we see that WPI growth has exceeded CPI growth.

The index we are using here is the total hourly rates of pay excluding bonuses for Australia, including private and public sector employment.

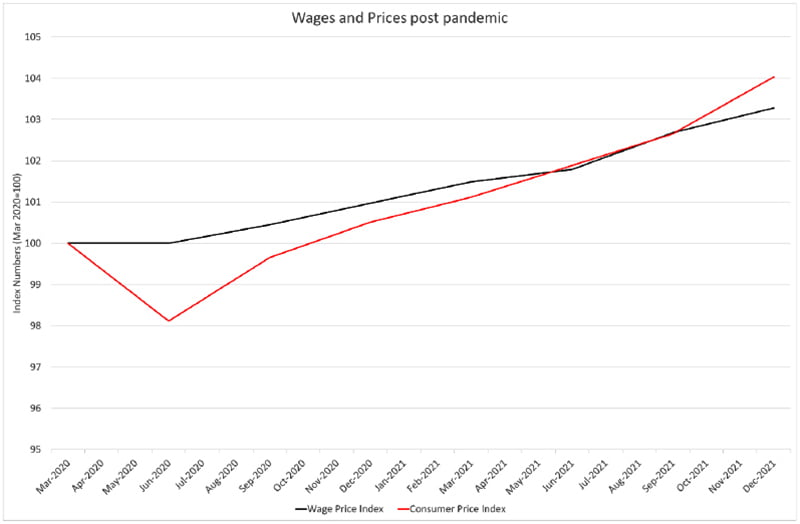

However, since the pandemic, WPI growth has trailed CPI growth.

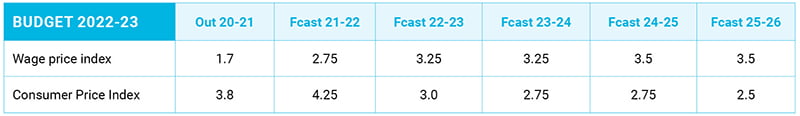

What made the issue more cogent has been that the 22-23 Budget forecasts a continuation of this trend out to the end of 2022 and forecasts a slight excess of WPI over CPI for the three outer years.

The Budget papers tried to deflect attention on this point by pointing to national accounts measures, saying ‘The national accounts measure of wages and labour income is expected to grow faster than the WPI measure, as it captures broader wage pressures resulting from a tight labour market.’

But, fundamentally, the national accounts measure how much people earn by doing multiple jobs or extra hours; it doesn’t provide an alternative measure of hourly pay rates.

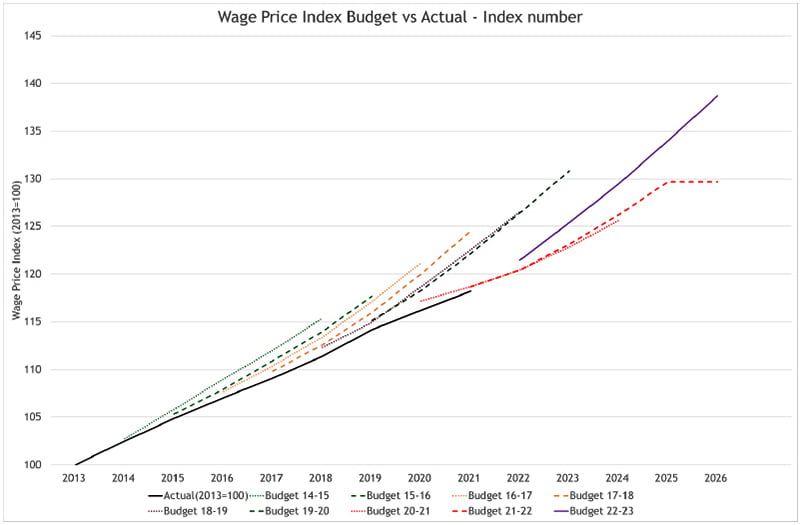

Added to the concern about the near-term forecasts is the record of previous forecasts. For example, the budget forecasts of WPI growth under this government are consistently above the actual growth rates.

So we can accept that wages growth has stalled and that all parties want it to resume. But neither side of politics seems to have any plan to restart wages growth.

The government refrain is that lower unemployment will result in greater competition for staff, driving wages up. However, while proposing this theory, the Coalition is keen to resume all forms of temporary migration, both skilled and guest workers, to counteract any effect.

Furthermore, there are good reasons to believe that the unemployment data is misleading since the definition of ‘employed’ is too broad and the statistics only count Australian permanent residents. (It can indeed be said that the correct answer to the question put to Anthony Albanese of ‘what is the unemployment rate?’ is that no one really knows).

However, Labor is no more convincing. Their proposals to move to more secure work, including the proposals for portable leave entitlements, will reduce the erosion of wages through contracting and casualisation. But that alone is not sufficient.

Both sides, however, assume that improved productivity will result in wages growth. This ignores the incentives of employers. They will only drive productivity growth to benefit themselves and their shareholders (or, in the public sector, taxpayers). If productivity does grow, their first preference is to bank the benefits for themselves.

The adage that ‘necessity is the mother of invention’ still mainly applies. In 1966 Harvey Leibenstein published his significant article Allocative efficiency vs. ‘X-efficiency’. He challenges the idea that the greatest impediment to economic welfare is market power and instead suggests that it is inefficiency inside businesses.

In fundamentally challenging the idea of the firm as a ‘profit maximiser’ working to ‘increase shareholder value’, he provides evidence that ‘The simple fact is that neither individuals nor firms work as hard, nor do they search for information as effectively, as they could.’

Herbert Simon had already described this behaviour in his 1947 book Administrative Behaviour, which he labelled ‘satisficing’ in 1956.

Anyone who has worked in a business that isn’t making its revenue target knows managers always find expenditure cuts of ‘discretionary items’.

The question then is how we get a business manager to innovate, given they are happy with the status quo. Here we are primarily talking about sustaining innovations rather than disruptive innovations.

Fundamentally something has to change in the environment. That can be the innovation of competitors. But it can also be the change in input costs.

If all we do with Industrial Relations reform is make it possible for businesses to pay their employees less, then that is what they will do when faced with financial stress.

If, however, wages increase, this forces the business to change its production technology to use less labour and more capital. Now businesses will react by saying that anything that increases labour costs will either be passed on as higher prices or will result in increased unemployment.

Neither is correct.

Any trade-exposed sector faces price limitations from goods and services produced in other markets. In addition, changes in production technology may use less labour per unit of output. Still, the total output should also grow as the increased wages increase demand domestically, and the business will become more competitive internationally.

This isn’t an argument for infinite wages. Instead, it is an argument for wage increases at the margin until the wage increases reach the point where they outstrip the capacity of technological innovation to compensate.

Although we cannot compute that point in advance, it can be discovered by slowly lifting wages and monitoring the consequence.

So rather than expecting productivity improvement to lift wages, we need to lift wages to drive productivity improvement.

The one place where the government can directly affect wages is with its own workforce. Under the LNP, the public service has only been allowed any nominal wage increase in return for productivity improvement. This is nonsense; management, not workers, generates productivity improvement.

Back in the heyday of the Hawke-Keating government, there was a grand national bargain trading wages for productivity improvement. But these improvements were about removing all kinds of restrictive practices, especially arguments over which trades had to do which jobs.

The capacity for the workforce to negotiate productivity improvement is illusory. In practice, it has been made up of numerous small changes like giving up early finishing on Christmas Eve as an entitlement, even though departmental secretaries still order the staff home early.

A second question is whether there are significant productivity improvements to be had in the labour-intensive service industries. Here what matters is the output you measure.

For instance, in healthcare, the ratio of hospital beds to population has declined from 30 per thousand to 15. This change reflects the shorter stay required for most procedures due to technology changes and the effect of preventative medicine.

It isn’t measured by student to staff ratios with teachers but by the amount of knowledge transferred. More time for teachers on teaching rather than developing ‘resources’ or marking can be realised by the reintroduction of standard textbooks and greater use of computerised marking. The latter can include little things like using grammar correcting software rather than being part of the human marking; the teacher can then concentrate on the content.

The increase in public sector wages will flow through into the private sector through competition for labour. A small increase in government wages should be Budget neutral as the government benefits from the increased tax on all pay raises and benefits from GST on extra spending.

Government can also intervene in Fair Work cases and advocate for pay rises, as Labor proposes for aged-care workers and the basic wage.

It seems pretty simple: all government needs to do is lift wages. An increase in wages will challenge managerial complacency and put more effort into the innovation and investment needed to lift productivity.

David Havyatt is a former telco executive, former adviser to Federal Labor Ministers and advocate on behalf of energy consumers. He is a long term observer of Australian innovation policy.

Note: In 1991-92, as General Manager, Sales Operations at Telstra, David Havyatt initiated and guided the project to introduce new remuneration programs, including contract (rather than award) employment for all sales staff. This utilised employment law changes made by the Keating Government.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.