After a week and a half of Nationals Party meetings and negotiations, Australia’s Long-Term Emissions Reduction Plan has been released. David Havyatt asks whether the plan is worth all the drama.

Sunday, 17 October 2021, at 4 pm, the 21 members of the National Party elected to the Senate and House of Representatives gather in their party room in Parliament House. They are there to receive a presentation from Energy and Emissions Reduction Minister Angus Taylor.

Taylor is presenting the plan already approved by a Cabinet, of which the Nationals Leader and Senate Leader are both members. Joyce is regarded as a “hardliner on issues such as climate change and coal”. He and his now Senate Leader gave the “slow creeping towards embracing a target of net zero emissions by 2050” as one reason for Joyce’s challenge for the leadership.

This was always going to be a tussle, but Prime Minister Scott Morrison knows the Nationals. For all their huffing and puffing, the only question is how big the pile of cash has to be before they can no longer see their claimed principles.

After a week of negotiations with the Treasurer (that’s the giveaway, isn’t it), the Nationals convened another Sunday meeting and agreed. But we had to wait for another Cabinet meeting on Monday before we could be told the result.

Somewhat bizarrely, the Prime Minister’s initial remarks on the release appear on his website as Opinion under the heading The Australian Way. The Opinion piece had run in the Daily Telegraph, but there is no reference to this on PM’s website. Strange.

Being politics in the 21st Century, an even snazzier summary (under the title The Plan to Deliver Net-Zero: The Australian Way) accompanied the already snazzily produced plan.

As an aside, the summary is 20 pages but 13Mb, while the plan is 129 pages but only 7Mb. (Oh, for the days when government reports were typeset in Courier and looked like they had just come off a typewriter and a skilled draftsman had laboriously compiled every chart.)

The documentation is too well designed (and printed) to be anything other than what Taylor presented to the Nationals nine days earlier.

Nothing in the announcements touched on the agreement with the Nationals, except the revelation at the press conference that the Productivity Commission will be required every five years to ‘monitor the impact, the socio-economic impact of our plans into the future’ particularly focussing on rural and regional areas.

This provision is eerily like the requirement for a regular report by a Regional Telecommunications Independent Review Committee that was part of the deal with the Nationals on Telstra privatisation. However, it differs, so far, in not being a legislated requirement.

Having established that what was released is the outcome of Angus Taylor’s months of effort and that it wasn’t cobbled together in the last week, it is not unreasonable to expect a detailed plan.

After all, that was Scott Morrison’s primary attack on Labor’s policy in 2019; he kept asking for the plan. He also requested Labor’s modelling of the costs of its plan.

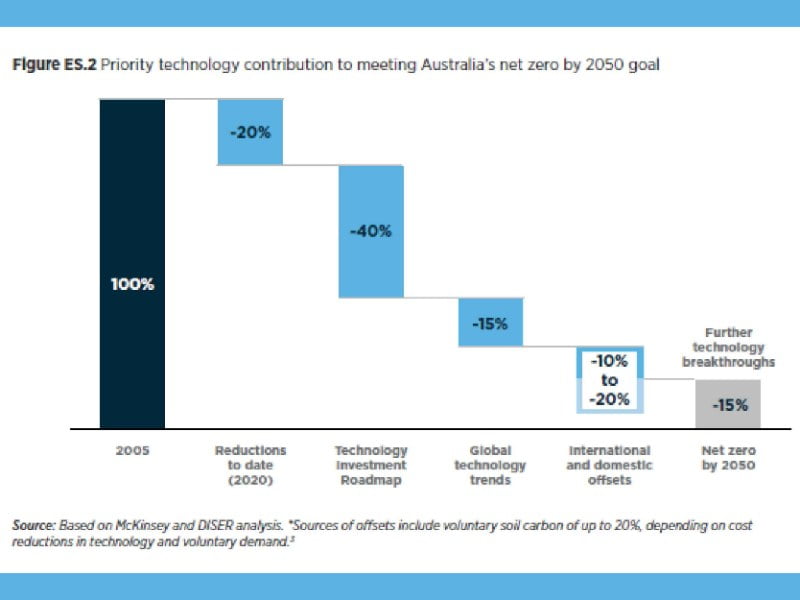

A plan describes an outcome and provides a detailed set of actions to achieve that outcome; the documentation delivered doesn’t constitute a plan. Figure ES.2 reproduced below conveniently summarises the government’s approach.

Because it starts with 2005 emissions, the remaining task achieves a further 80 per cent reduction. Of that fully half is delivered through the Technology Investment Roadmap.

Interestingly the government’s webpage on the Roadmap says ‘annual low emissions statements are key milestones of the roadmap process.’

The first was delivered in September 2020. There hasn’t been a separate low emissions statement issued under the roadmap as part of this announcement.

Yet, the plan repeats the commitment to ‘review our progress towards the Technology Investment Roadmap stretch goals on an annual basis, through successive Low Emissions Technology Statements (LETS).’

How the other half is achieved is more interesting. Confusingly, one component is specified as a band, suggesting Australia could reach anywhere between net-zero and minus 10 per cent of 2005 levels by 2050.

To simplify, the remaining half is almost equally divided between three categories. These are global technology trends, international and domestic offsets, and further technology breakthroughs.

I agree with the proposition that the pace of technology improvement in many sectors is remarkable, including the cost reductions in solar generation and battery storage. The rate of technology improvement is not only remarkable; it is perpetually being underestimated (unless it is the delivery of a nuclear fusion reactor). But there is a risk of double counting since the roadmap already has ‘stretch goals’ (don’t you love the management consultant language).

As one of the economies most well endowed with renewable resources and landmass, Australia should be planning on being a net exporter of international offsets, not an importer. It is unclear what domestic offsets could be when land-use change, soil carbon, and carbon capture and storage are otherwise already included in the plan.

Observant readers will have noted that the chart is based on McKinsey and DISER analysis. The plan itself said, ‘Analysis to inform our Plan was commissioned from the Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources (DISER) and McKinsey & Company (McKinsey).’ The plan references the McKinsey analysis 24 times.

At the press conference, the Prime Minister committed to releasing the modelling ‘at another time.’ Whether that will be proactively released before a Freedom of Information request drags it out will indicate the Government’s faith in the plan.

The plan is not only short on detail but also on near-term aspiration. Current projections are that emissions reduction by 2030 will be 30-35 per cent, well above the 26-28 per cent target – emission reduction of 35 per cent level is consistent with the aggregate of State targets.

The Prime Minister explains his reluctance to change the target as being based on his commitment to the Australian people at the last election. That is, however, merely a convenient cover for having targets that the PM can repeatedly say he will ‘meet and beat.’ It seems stretch targets aren’t so good when they apply to current activity.

This brings us to the one place where the plan truly shines; never before has an Australian government plan been better at providing (or repeating) campaign slogans. In his media release, the PM said:

“The Plan is based on our existing policies and will be guided by five principles that will ensure Australia’s shift to a net zero economy will not put industries, regions or jobs at risk. The principles are: technology not taxes; expand choices not mandates; drive down the cost of a range of new technologies; keep energy prices down with affordable and reliable power; and, be accountable for progress.”

It is hard as a commentator not to want to dissect these methodically, but I will restrict myself to the first two principles.

The intent of putting a price on carbon (that the Liberals continue to brand a tax) is to facilitate technology investment by incorporating in prices the cost of the externality (carbon emissions). It works by informing the choices of individuals with the full environmental cost of their decisions.

The government bases its alternative on programs that involve direct government investment in technology and government expenditure of emissions reduction activity (the Emissions Reduction Fund). The government gets its money from taxes, and citizens have no choice whether they pay their taxes.

The document produced is a political manifesto, not a plan. It delivers a weird combination of hope and outright lies.

As an example of the latter, I refer to the Prime Minister’s assertion that the plan ‘will not cost jobs, not in farming, mining or gas, because what we’re doing in this plan is positive things, enabling things.’

Despite its many weaknesses, it is still a highly valuable document. The commitment to Net-Zero by 2050 means that people who really do plan, in both the public and private sectors, can fill in more detail.

For example, the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) has had to regard Net Zero as an aspirational scenario in developing its Integrated System Plan. It can now build its plan with Net Zero as its central scenario.

As the Prime Minister notes in the quote above, the plan is based on existing policies. If so, one is left to ask why it has taken so long to deliver. The answer is simple, the cumulative evidence on Australian attitudes to climate change is now too strong to ignore.

Reader challenge: The summary plan goes by the title of The Plan to Deliver Net-Zero: The Australian Way. The Australian Way was also the title of the PM’s Opinion piece. We ask readers to use the Comments function below to let us know what part of the plan, other than the fact the Australian government produced it, makes it the Australian Way.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.