Despite a high proportion of globally ranked universities, Australia’s research impact, business R&D investment, and proportion of R&D expenditure relative to GDP, remains low.

The contribution of the higher education sector to national R&D efforts accounts for 35 per cent of national R&D, much higher than the average in comparable nations other than Canada. This reliance on the higher education sector underscores a structural imbalance compared to countries where business sector contributions are more dominant.

To better understand the scenario, in 2023, the Acton Institute for Policy Research and Innovation conducted a study to examine the institutional settings for research systems in Australia, Canada, Germany, Israel, South Korea, the UK, and the USA.

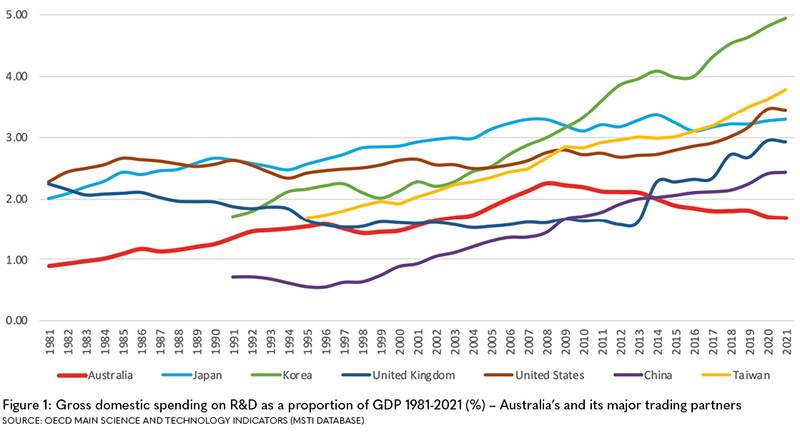

In 1981, Australia spent 0.9 per cent of its GDP on R&D – the lowest among its major trading partners – Japan, Korea, the UK, USA, China, and Taiwan. Forty years later, in 2021, the proportion is still the lowest, at 1.68 per cent.

Not only that, as shown in Figure 1, Australia (red line) is falling further behind in its commitment to R&D. The commonly used three per cent benchmark is shown in Figure 1 for information.

The OECD estimates that in the latest years for which data is available, for the countries included in the study, together with other Australian competitor countries, 67.8 per cent of R&D funds were sourced from the business sector, 20.7 per cent from the government, 2.5 per cent from higher education, 6.5 per cent from the rest of the world, and 1.8 per cent from the private, not-for-profit sector.

OECD data also indicates that, on average, for the countries included in the study, together with other competitor countries, the business sector contributes 76.1 per cent of national expenditure on R&D, higher education 10.6 per cent, government 11.2 per cent, and the not-for-profit sector 1.8 per cent.

The Australian higher education sector contributes 34.8 per cent of the national R&D effort, while other countries with a higher education contribution of over 20 per cent are the UK (22.5 per cent), France (20.1 per cent), The Netherlands (27.8 per cent), Sweden (23.7 per cent), and Singapore (24.2 per cent).

The data assembled for the project indicates that, internationally, Australia has comparatively high levels of research output but a disappointing impact. While output is heavily concentrated in the life sciences, there is a long tail of comparatively small output levels across all categories. In some of these areas, performance is rated very highly with impact metrics, particularly in information and computing sciences.

The falling level of R&D in Australia reflects some underlying but fundamental systemic issues.

Comparative institutional frameworks

Each country’s research system is complex, with multiple organisations with varying roles and responsibilities for making resource allocation, research delivery, quality, and accountability decisions.

There are also complex interfaces between the science and engineering systems and the innovation systems. Countries adopt a range of institutional arrangements for research investment vehicles to establish national strategies, allocate resources, and secure accountability.

Research investment arrangements in Australia appear to be highly fragmented, with responsibilities held in numerous ministerial departments, statutory authorities, and funding Councils.

Delivery arrangements are also widely distributed across universities, public research organisations, medical research institutes, Cooperative Research Centres (CRCs), Australian Research Council (ARC) research centres, departmental research divisions, and bureaus.

The absence of a national research foundation or similar entity in Australia creates a vacuum in coordination and leadership. Countries with national research foundations include Germany (established in 1951), the US National Science Foundation (1950), the National Research Foundation of Korea (2009), the Israel Science Foundation (1972), and the Singapore National Research Foundation (2006).

In Canada, the national public research system includes Innovation, Science, and Economic Development Canada, advisory councils, research investors, tri-agency councils, and application and criteria-driven research funds.

Canada has 223 public and private universities, 213 public colleges and institutes, and the National Research Council of Canada. The country also has numerous research institutes conducting scientific research to support a larger mandate.

In Germany, the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) funds applied research projects, particularly in areas of strategic importance to Germany, such as energy, health, and mobility.

The German Research Foundation (DFG) is endowed by the federal (69 per cent) and state (30 per cent) governments. In 2021, it funded more than 31,600 new and ongoing projects with a funding volume of €3.6 billion.

Germany’s national research system is characterised by an intensive, highly organised, centrally directed, and “rational” public research organisation structure. The system consists of 456 universities, 112 general universities, 236 Universities of applied sciences, and 108 colleges.

There are also 38 medical research institutes and 279 Collaborative Research Centres. The Fraunhofer Society, Helmholtz Association, Leibniz Association, and Max Planck Society play critical roles.

Israel has a less complex research system with ten universities and 53 colleges. It spends a similar amount on R&D to Australia but with just over a third of the population. Business spends over 90 per cent of the R&D effort.

Korea’s national public research system has 190 universities, 134 junior colleges, and 45 graduate schools.

In the UK, nine research councils under UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) fund and engage with English higher education providers.

Other research investors include the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC), the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR), the Research Capital Investment Fund, the Expanding Excellence in England Fund, the International Investment Initiative, the Research England Development Fund, and the UK Research Partnership Investment Fund. The Advanced Research and Invention Agency (ARIA) is a new agency that will support high-risk, high-payoff research.

The US has a diverse research system with various institutions, including the National Science and Technology Council, National Science Foundation, National Institutes for Health, National Institute of Standards and Technology, Department of Energy, Department of Defence, and Department of Agriculture.

The US National Science and Technology Council is a cabinet-level council of advisers to the President on Science and Technology (S&T).

Australia has the highest percentage of globally ranked universities in the world, with 84 per cent of Australian universities ranked. Nine universities are in the top 100 of most ranking systems, but none are in the top 10. Many countries, including Germany, are not motivated to score highly in ranking systems.

Stakeholders

The role of stakeholders in higher education research systems is complex, as all countries have a large inventory of organisations representing and advocating for the interests of their members, including research policies and funding.

Learned academies play a crucial role in research investment, particularly in countries like Germany, Korea, the UK, and the USA. These academies provide independent, objective advice to inform policy, spark progress and innovation, and confront challenging issues for the benefit of society.

In Germany, the Union of German Academies, the Council of Canadian Academies, the US National Academies, and the American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS) contribute to research investment.

In Australia, the Australian Council of Learned Academies is a forum where academics and their associate members come together to contribute expert advice to inform national policy.

The Council of Canadian Academies evaluates the best available evidence on complex issues. It convenes experts in their respective fields to serve as members of its Board of Directors and Scientific Advisory Committee.

Germany’s Union of German Academies is the umbrella organisation of eight academies. The Academies’ Program is the largest long-term research program in Germany for foundational research in the humanities and social sciences.

The Korean Federation of Science and Technology Societies (KOFST) works with the Korean government to promote scientific and technological advancement and foster collaboration between Korean scholars and international counterparts.

In the UK, 162 organisations identify as learned societies, including The Royal Society of London, The British Academy, and The Royal Society of Edinburgh.

The National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine in the USA provide independent, objective advice to inform policy and address challenging issues. Professional associations and societies, including engineers, architects, designers, accountants, lawyers, and medical practitioners, have increased their advocacy and government relations activities.

Several formal organisations have been established to promote university-industry collaboration. The UK National Centre for Universities and Business (NCUB) promotes collaboration between universities and businesses through initiatives such as the Talent 2030 Campaign, the University-Industry Collaboration Toolkit, and the Student Innovation Awards.

The Business and Higher Education Roundtable (BHER) in Canada promotes collaboration between businesses and post-secondary education institutions to develop innovative solutions to workforce development challenges and help businesses and post-secondary institutions collaborate to create opportunities for students and graduates.

Research intermediary organisations are researcher-oriented rather than institution-oriented, although personal connections may become reflected in institutional collaborations.

Innovation intermediaries are essential for facilitating collaboration and technology transfer between universities and industries. These intermediaries act as brokers, mediators, and supporters of innovation processes, helping to bridge the gap between academic research and commercial application.

Some intermediary initiatives include the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), the EU Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions Program, the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), the Fulbright Program, and the Australia New Zealand Association for the Advancement of Science (ANZAAS).

Funding streams

All research systems rely on a significant amount of direct government funding through a wide range of channels. Tax credits, or “tax expenditures” provide the most significant level of support for R&D in countries in the study (except Germany).

Universities increasingly issue financial instruments (bonds or other debt securities) to finance capital expenditures, particularly large-scale infrastructure projects such as research facilities or laboratories.

Public-private partnerships are contractual arrangements between universities and private sector entities to jointly deliver university buildings and facilities, including those for research. These partnerships allow universities to preserve cash and relieve pressure on government budgets, with clearance from State Treasuries generally required.

Similarities and differences

The scale and scope of R&D varies significantly between countries, with the US spending US$672 billion, China US$475 billion, Japan, Germany, and Korea each having R&D expenditures over US$100 billion, Canada and Australia forming a third tier, and Israel at US$17.1 billion. These systems cannot replicate the research diversity and intensity of the USA, Germany, and Korea, as they require sub-scale operations and fragmentation in institutional frameworks.

Australia and Canada share similarities in their federal structure, with responsibilities in education and research shared between a central government and state/provincial governments. Both countries have low proportions of R&D in GDP and rely heavily on higher education to build the national research effort.

They invest significant funds for research through ministries/departments, with Canada having more investment funds than Australia. They also have a portfolio of national research centres and institutes and many research centres within ministry/departmental structures to perform mission-based research.

The research systems in each country are highly complex, with multiple organisations with varying roles and responsibilities for decision-making regarding resource allocation, research delivery, quality, and accountability. Canada does not have a national research strategy, but strategies are embedded in individual research councils and separate ministries.

Germany places relatively greater importance on government R&D, with 14.4 per cent of the total research effort being spent on it.

Israel’s administrative model is influenced by European, British, and American systems, with public research funding largely driven by the government. Israel’s research sector is closely integrated with industry, aiming to drive economic growth, entrepreneurship, and commercialisation of research outcomes.

The Korean research system has a unique advantage due to the close involvement of global corporations in higher education research.

The Australian research culture tends to emphasise academic freedom and a collaborative approach across institutions and disciplines. At the same time, Korea has a strong focus on applied research, technology transfer, and industry collaboration.

The Australian and US systems for funding public research are vastly different. The US R&D investment is heavily concentrated in several states, each with parallel research systems, specialisations, and research-intensive corporations.

With a population of 40 million, California has three public university systems with different missions. Differences in scale and scope may constrain what can be expected and achieved when examining international practice and experience.

Each country has an organisation with a specific focus on innovation, such as Australia’s Department of Industry, Science and Resources, Canada’s Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED), Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWi), Israel’s Israeli Innovation Authority Programs, Korea’s Institute of Startup and Entrepreneurship Development (KISED) and BIRD Foundation, the UK’s Catapults and Innovation Centres, Scotland’s Innovation Centre program, and the Research Wales Innovation Fund (RWIF), Knowledge Transfer Partnerships (KTP), and Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund (ISCF).

The USA has funding for NSF Regional Innovation Engines ($300.0 million), Accelerating Research Translation (ART) ($45.0 million), and NSF Convergence Accelerator ($100.0 million). The National Science Foundation’s Engineering Research Centres (ERC) supports convergent research, education, and technology translation at US universities, which will have a strong societal impact.

Over the last 20 years, the number of technology transfer offices in universities has significantly increased due to increased funding for R&D and growing recognition of the economic and societal benefits of technology transfer.

Innovation intermediaries and networks play a crucial role in supporting collaborative activities in the innovation process. They act as agents or brokers, provide information about potential collaborators and broker transactions, act as mediators between existing collaboration bodies, and help find advice, funding, and support for innovation outcomes.

Conclusion

The study points to the significance of differences in international research systems in terms of coordination, investment, policy development, and research delivery.

Several countries have set targets to achieve three per cent or more of R&D expenditure in GDP, with the European Union proposing this in 2000 as part of its Lisbon strategy.

Korea, Israel, and Germany have also committed to reaching a three per cent R&D expenditure target.

However, Australia’s devolved administrative structure and fragmented landscape of research institutions may not be capable of delivering such a massive increase in the short term from the current 1.68 per cent.

The study examined research policy issues concerning global research-intensive companies, focusing on the US, UK, Germany, and Korea.

Global technology, motor vehicle, and pharmaceutical companies dominate the global 1,000 research-intensive companies, but very little of this investment occurs in Australia.

Many universities, public research organisations, and medical research institutes have taken initiatives to create research infrastructure from their own resources to encourage business R&D investment and manufacturing activity.

Australia could encourage global technology-intensive companies to partner with Australian universities to increase their commitment to R&D in Australia through collaborations around major university-owned research infrastructure facilities and equipment.

Many countries have or are developing national research strategies, often in concert with science and innovation strategies.

Germany has instituted a Pact for Research and Innovation to strengthen large non-university research organisations and the German Research Foundation by creating stable financial conditions and freedom of movement needed for cutting-edge research at the international level.

Dr John H Howard is executive director of the Acton Institute for Policy Research and Innovation (www.actoninstitute.au). Dr Howard is also a visiting professor at the University of Technology Sydney.

This article is part of The Industry Papers publication by InnovationAus.com. Order your hard copy here. 36 Papers, 48 Authors, 65,000 words, 72 page tabloid newspaper + 32 page insert magazine.

The Industry Papers is a big undertaking and would not be possible without the assistance of our valued sponsors. InnovationAus.com would like to thank Geoscape Australia, The University of Sydney Faculty of Science, the Semiconductor Sector Service Bureau (S3B), AirTrunk, InnoFocus, ANDHealth, QIMR Berghofer, Advance Queensland and the Queensland Government.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.