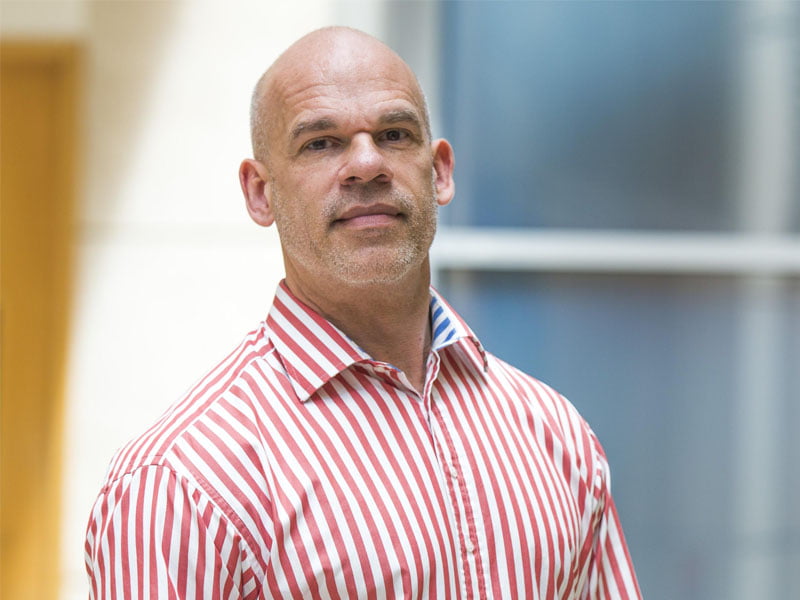

Former Digital Transformation Office chief executive Paul Shetler says it’s not too late to reset the troubled My Health Record project, and that there are strategies government can adopt to give the program a better chance of success.

But doing nothing is not an option. In its current format, the My Health Record project “is either going to crash and burn, or its going to be a slow-motion failure, not unlike what’s happened in the UK,” he says.

Mr Shetler, who is a co-founder and partner at consulting house AccelerateHQ, says mitigating against the reputational damage of a project failure is paramount, but that a redesign of the data handling is an opportunity for government to take a lead.

“The first thing I would do is acknowledge there is a problem, and that they inherited a previous health record [the PCEHR, or personally controlled electronic health record], which nobody wanted,” Mr Shetler told InnovationAus.com.

“But rather than trying to dragoon people into it using an opt-out – which is really the heaviest form of pressure – they should put an immediate pause on the project and acknowledge that they have heard what the public are saying,” he said.

“And then they should reset the program, returning it to an opt-in system as the very the very first step. It should be absolutely voluntary.

“And then they need to look closely at the very substantive issues that people are raising about data [within My Health Record] – the integrity of it, the security of it, and the privacy of it.”

Mr Shetler says government should be looking at introducing GDPR-style data controls as a central plank in turning the project around. By taking a lead when it comes to privacy and data security, the MHR redesign is an opportunity to rebuild trust in an area where government has struggled.

It should be a basic tenet of any system holding data as sensitive as health records that data cannot be shared by default – that it can only ever be shared via affirmative consent. And when a citizen deletes a record, it is completely expunged from the system, rather than waiting for 30 years after that citizen’s death as is the current practice under the MHR.

“This is really important. They are calling this My Health Record. But right now, this is a Government Health Record, about you,” Mr Shetler said. For it to be your health record, the citizen really has to own the data.

“Let the user actually own the data. That’s a massive point. And when the user wants to check the data out (remove), then it is physically expunged from the system. People don’t trust government to do these things right now.”

Mr Shetler estimates the federal electronic health record program – over its various permutations – has cost around $2 billion. This is an ominously large number for government, creating a “sunk cost fallacy” where people working on the system fear that so much has been invested already that its not possible to abandon.

Mr Shetler says a pause followed by a re-set is the only way this projects avoids becoming a spectacular waste of money.

A pause in the program would give the Australian Digital Health Agency an opportunity to first better understand what users want from a digital health record, and secondly to better define – and articulate – what success looks like in relation to a digital health record.

But simply stonewalling the widespread criticism of the MHR, and delivering false statements about what government agencies have access to the data under the legislation will continue to undermine trust.

“You can’t go to people with a name like My Health Record and then just ignore what people say they want in that record. All of these things require trust, and they’ve just demoted it,” he said.

“All of their actions [in the MHR roll-out] are those of people who don’t seem to care about having a trusted relationship with their users. They are just trying to enforce this system through dictate, and that is absolutely the wrong way to go about doing things.”

Defining and articulating metrics for success are crucial. If the system is designed for the benefit of the users, the success metrics give those users a reason to become actively engaged with the system.

“They have never said what they hope to achieve by doing all of this. How will they know when it is a success? And what metric will they use to measure that success? They have never said.

“For a program that has cost $2 billion and for government to not actually know how it will say whether it has been a success or not seems odd.

“That does not sound like a well-run program to me”

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.