A significant data breach involving the federal government’s My Health Record is “just a matter of time”, digital rights advocates argue, as the three month opt-out period begins.

Civil rights and digital privacy advocates are calling on Australians to opt-out from the digital health record over privacy and security fears, while politicians from both sides of the aisle have called on the public to embrace the service.

In a further blow to the service, the government’s online opt-out online platform buckled under the weight of interest during the first day of the three month window, while users reported wait times of several hours in trying to cancel their My Health Record (MHR) over the phone.

MHR is an online summary of an individual’s medical history as uploaded by the user or a doctor, detailing the likes of allergies, medical conditions and medication.

The government, along with several health bodies, argue the service will improve medical care. The service is overseen by the Australian Digital Health Agency (ADHA).

MHR was launched six years ago as an opt-in service requiring informed consent from users.

Last year it was announced that the government would be shifting it to an opt-out service, with all Australians being given a digital record unless they expressly decide not to within a three month period.

Once an account is made, a user can choose to upload two years of Medicare Benefits Scheme, Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, Australian Immunisation Register and Australian Organ Donor Register data.

If a doctor accesses the digital record before the user makes this decision, the data will be automatically uploaded.

The three month opt-out period kicked off on Monday.

Australians are now able to opt-out from the service using the online portal, over the phone or in paper form in the mail.

If a citizen doesn’t opt-out during this window, any data that is uploaded to their digital health record will be stored until 30 years after their death.

Even if they later decide to cancel their MHR, this will merely deactivate it and not completely delete the data.

Digital rights groups including Electronic Frontiers Australia and the Australian Privacy Foundation are encouraging Australians to opt-out of the service over security and privacy concerns.

“There are just so many ways for this thing to go wrong, and it’s that cumulative risk that we think makes the system so very dangerous.

(We are) deeply concerned about the system being forced on people without their positive, informed consent,” Electronic Frontiers Australia board-member Justin Warren told InnovationAus.com.

“People with sensitive health issues – mental health issues, those with conditions such as HIV or other sexually-transmitted infections – would need to be particularly careful when using the system.”

Australian Privacy Foundation health committee chair Bernard Robertson-Dunn said the government has not adequately demonstrated that the potential benefits of the digital health record outweigh the number of concerns surrounding it.

“Nobody has provided a convincing argument that giving your health data to the federal government has any clinical or other benefit.

The government is also not making it clear that many, if not all, the claimed benefits can be achieved by individuals in other ways that also deliver additional benefits such as appointments, repeat prescriptions and access to GP systems where the bulk of a patient’s health data resides,” Dr Robertson-Dunn told InnovationAus.com.

“Such solutions have a lower overall risk and do not involve giving health data to the government, which is probably the greatest risk considering the lack of clarity from the government regarding its potential use of such data.”

A primary concern surrounding MHR is that such a large collection of potentially valuable and sensitive medical data stored in the one place will act as a “honeypot” for hackers, especially in light of the government’s checkered recent history in digital projects.

“There are inherent risks in having a single central database of valuable health data. It’s a very attractive target for cyber-criminals.

“The government hasn’t demonstrated that it can be trusted with sensitive information.

“Australian governments don’t have a great track record with IT systems and information security in general,” Mr Warren said.

“Information security is really hard, and this is a single system containing the private health information for the entire populace, viewable by every healthcare provider in Australia.

“It’s a very attractive target for cyber-criminals. We believe a data breach is just a matter of time.”

Opposition leader Bill Shorten also pointed to the government’s recent IT bungles, but offered his support to MHR.

“I don’t blame people for being skeptical about this government in terms of the way it implements digital change programs. Let’s never forget the census.

”I can understand why people are concerned, but I say, don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater. Let’s make the scheme work rather than give up on the scheme,” Mr Shorten told the media on Monday.

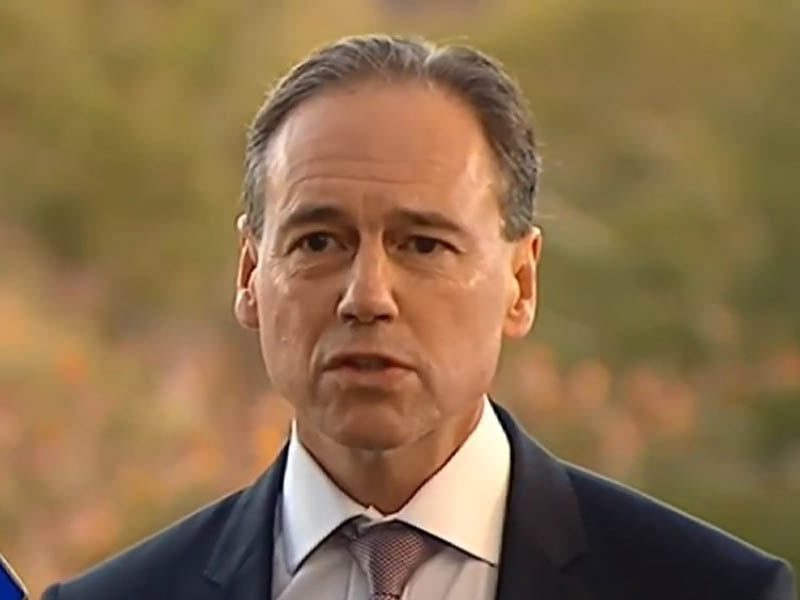

Addressing the media on Monday, Health Minister Greg Hunt defended the digital health record, and said all the data stored is secured.

“It’s been operating for six years and there are almost six million Australians that are enrolled, and the advice from the head of the Digital Health Agency is that there have been no breaches.

“It’s not just bank-level security, but it’s defence tested. They have a permanent cyber-security network.

“It’s arguably the world’s leading and most secure medical information system at any national level,” Mr Hunt said.

Concerns have also been raised over how the data stored on MHR will be stored with secondary parties and law enforcement.

The government has confirmed that it will allow second parties to access anonymised data for research and other purposes, with users having to actively opt-out of this service.

Data on the record will also be handed over to law enforcement without a warrant if it “reasonably believes” it’s necessary for preventing or investigating crimes, and for “protecting the public revenue”.

Making the automatic settings be to provide as much data as possible is an abuse of trust, Mr Warren said.

“We are concerned that the system has been rapidly converted from an opt-in system to an opt-out system, and so its fundamental design assumes that information in the system is there to be shared, not kept private and secure,” he said.

“Most people never change the defaults, and the ADHA knows this.

“An opt-in system should be configured to require you to deliberately allow access so that your data is secure and private by default. We think a lot of people are going to accidentally expose their data to people they didn’t mean to.”

The federal government said it had launched a national communication strategy to inform Australians of the digital record amid concerns that the majority of the general public will not have even heard of it until after the opt-out period ends.

But digital rights advocates said the government’s advertising is only talking up the potential benefits, and not informing Australians of the possible risks.

“The promotional material that the government is providing to the public speaks only about potential benefits which may or may not be relevant to the average Australian.

“What the government is not providing is any information about the costs to patients and GPs, or the very real risks of the system,” Dr Bernard-Dunn said.

“The ADHA has made a concerted effort over the past couple of months to talk up the benefits of the system, but hasn’t spent nearly enough time explaining the risks to people, particularly vulnerable groups who have the most to lose,” Mr Warren said.

“ADHA’s incentives are set up to encourage them to downplay the risks, but that services their own interests not those of vulnerable groups who will be hurt if things go wrong.

“We sincerely hope that no-one gets hurt by this system, but our experience tells us that it’s likely they will be. That’s why we’re worried.”

The National Rural Health Alliance has thrown its support behind the service, saying there is “simply no good reason to opt out”.

“Simply put, My Health Record can save lives. If you live outside a major city, you have less access to health services, and are more likely to delay getting medical treatment. That means you’re more likely to end up being hospitalised.

“A My Health Record means that all your important health information is at your fingertips of your doctor, nurse or surgeon,” NRHA CEO Mark Diamond said in a statement.

“There is always a risk with online information. But the Alliance is satisfied that the Australian Digital Health Agency is using the most robust security measures to safeguard people’s health records, and the risk associated with My Health Record is small.

“I ask all country people to balance that small risk against the considerable advantages of My Health Record.”

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.