It turns out that the two lightest reactive elements (excluding the noble gas helium), hydrogen and lithium, are central to our energy future, but neither is an energy source.

Hydrogen can be both an energy carrier and store, while lithium is used to store energy but can also be mobile. Not surprisingly, a lot of interest is focused on both.

As InnovationAus has reported, the CSIRO has released a study noting that the Australian energy system needs a fourteen-fold increase in storage to meet the net-zero goal. This need is not news.

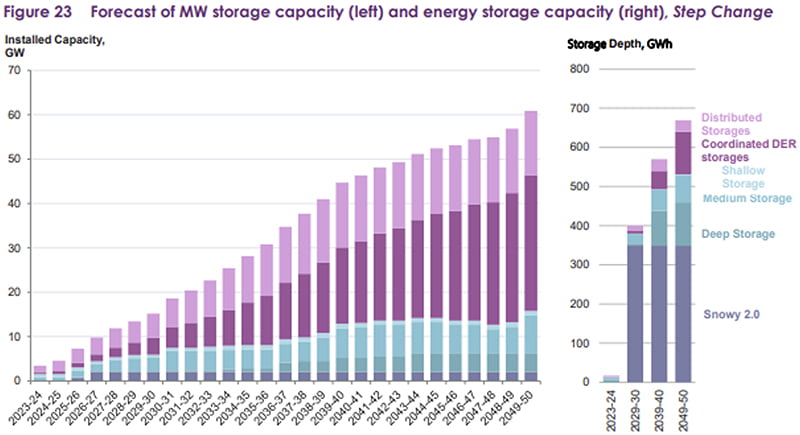

The Australian Energy Market Operator’s 2022 Integrated System Plan already noted a need for 46 GW / 640 GWh (gigawatt hours) of dispatchable storage, in all its forms, by 2050, adding:

The most pressing need in the next decade (beyond what is already committed) is for dispatchable batteries, pumped hydro or alternative storage to manage daily and seasonal variations in the output from fast-growing solar and wind generation.

The impact of the delays in Snowy 2.0 should not be underestimated, nor should Malcolm Turnbull’s approval of the project after two weeks of analysis be left without scrutiny. The magnitude of this error dwarfs his mismanagement of the NBN.

Various storage technologies exist, ranging from chemical battery storage to physical storage, including off-river hydroelectric resources.

Storage can also be located in different locations, but for relatively obvious reasons, it is best located between generation and loads (a problem with Snowy 2.0) and ideally close to either. As the AEMO chart above shows, an enormous amount of storage capacity that will serve short-duration needs comes from storage within the distribution network.

The CSIRO paper only considered the half of this regarded as coordinated storage (also known as virtual power plants). However, proper wholesale and network price signals should enable other distributed storage to adapt equally well to total system needs.

A large part of this storage will be what some stakeholders, such as Energy Consumers Australia, refer to as Customer Energy Resources rather than Distributed Energy Resources.

Unfortunately, the list of stakeholders consulted by the CSIRO (page 183) did not include any organisation that represents these consumers or even the innovative energy supply companies that engage with them.

But this is the least of the problems with the CSIRO report. The report encourages further investigation of alternate battery technologies and deeper storage technologies.

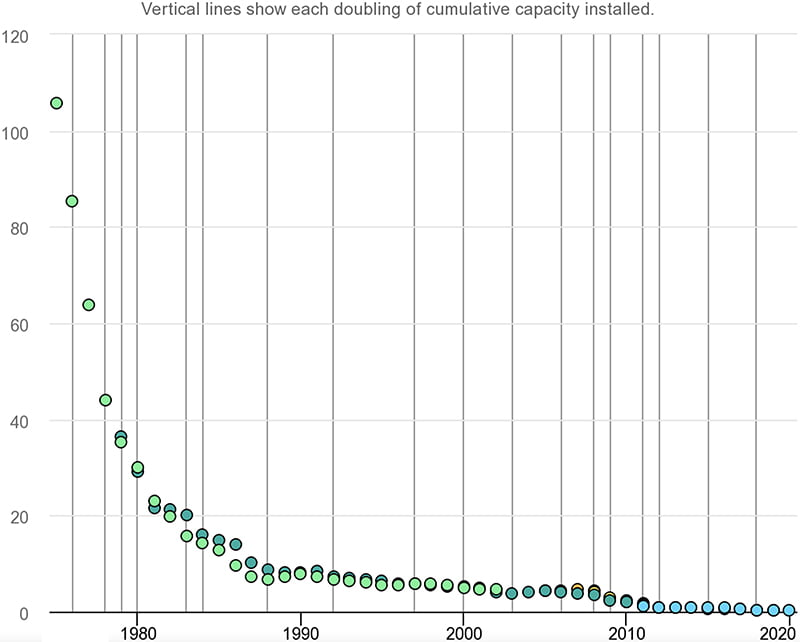

These are good recommendations, but strategically the value in energy markets comes from exploiting the “experience effect”, which is the process by which the price of technologies drops exponentially as cumulative production increases.

This effect is well demonstrated with solar PV costs.

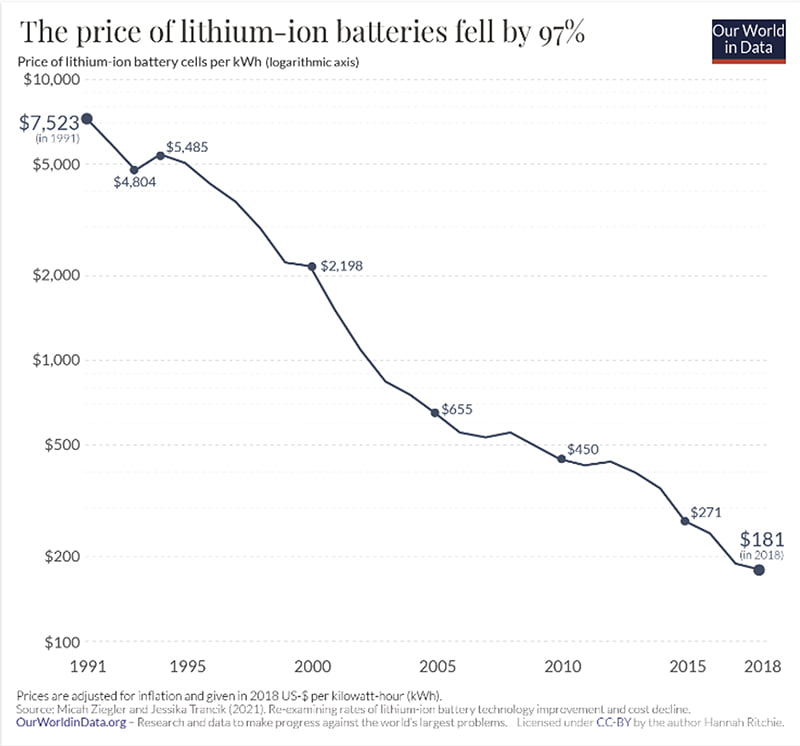

A similar tale is evident with Lithium-ion batteries.

Alternative technologies must offer a significant upfront and immediate cost advantage to outweigh this experience effect.

The situation is slightly different in physical storage, but the biggest issue there has been the overhang created by a pumped hydro project that is too big and in the wrong place

Furthermore, this is an on-river project that may never realise its advertised availability due to flood mitigation constraints.

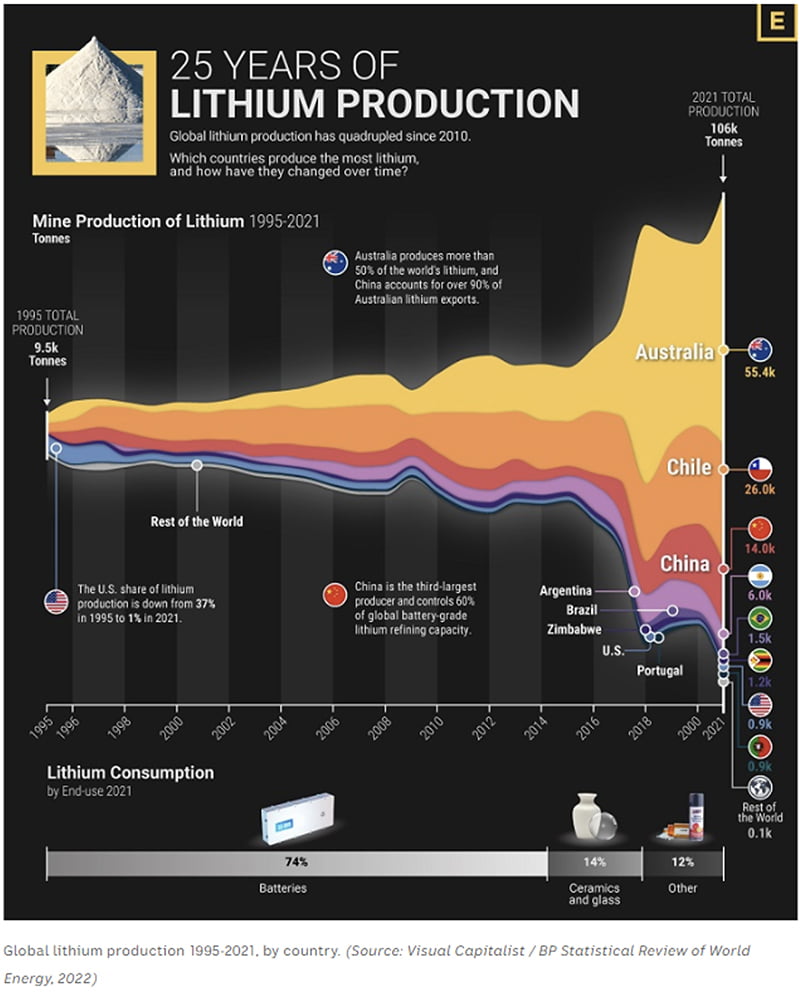

Furthermore, the report underplays the extent of lithium-ion batteries’ “supply chain” constraints. These constraints are two-fold. The first is the simple extraction and refining of lithium; the second is the fabrication of batteries.

Both of these are exacerbated by the amount that flows through China and are already subject to growing reliability concerns and would prove fragile in possible but unlikely geopolitical scenarios.

The CSIRO response is to “Consider and develop strategies to de-risk battery supply chains through a number of strategic diversification pathways, including, but not limited to: developing domestic value chains; developing resource circularity; and investing in research, development and demonstration (RD&D) for alternative battery chemistries.”

We have already dealt with the last.

The good news is that Australia is already the world’s largest lithium miner.

According to the Wall Street Journal last month, the world is looking to Australia to refine its lithium. And while three Australian producers are setting up refining facilities, they are dwarfed by what the owner of one of them, Albermarle, has just announced in the US.

A $US1.3 billion plant in South Carolina has been spurred by the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act. To qualify for subsidies under the Act, EVs need batteries not sourced from “an entity of a foreign concern” (that is, China).

It is a year-and-a-half since then Prime Minister Morrison announced that the Quad meeting had prioritised the critical minerals for the new economy.

Unfortunately, while there has been a change of government, there has been very little to show for it. However, the government has commenced consultation on the Critical Minerals Strategy.

The new government’s National Reconstruction Fund tends to focus on advanced manufacturing opportunities; with the Act passed, lobbying will focus on the investment mandate for the fund. However, the focus will likely be on shiny new things like tech and space.

Meanwhile, there is speculation about whether Australia could restart an automotive industry based on electric cars. (Note the consultation on Australia’s National EV Strategy was focussed on uptake, not manufacturing.)

Automotive manufacturing, of course, was where just-in-time processes and vast global supply chains (of which Australia is still a part) began.

For good economic reasons (based on the economic theory of contracts and the problem of incomplete contracts), new technologies like EVs are amenable to tighter vertical integration, such as Tesla. But the growth of EVs has reduced the benefit of integration in manufacturing.

Most importantly, at the heart of all EVs are the battery packs. But big lithium-ion battery packs comprise a host of smaller batteries designated 18650, each just a little larger than the standard AA battery.

One of the secrets to Tesla’s success was how these were packaged together, including what is, in effect, an operating system. As a result, early Tesla owners occasionally suddenly got an increase in their maximum range purely from an update in battery control software.

Australia has a choice on how much extra investment we want to make in lithium processing (which may include limiting the amount of ore lithium miners can contract to export).

We then need to choose how much of that processed lithium we want to turn into batteries ourselves or whether we have any preferences for diversified markets for processed lithium.

Left to its own devices, the “market” will keep doing what it has always done and export ore to China, or if we refine it, export the lithium hydroxide to China.

To make “decisions”, the country has various policy choices, such as how the US used EV subsidies.

Given the tight employment market, one simple metric should drive how far up the value chain we go. That is the ratio of increased GDP per employee; the goal is output growth, not growth in labour input.

An EV industry should only be contemplated if we build a successful battery industry. Making lithium-ion batteries is not a simple task, and like other advanced manufacturing opportunities, Australia’s limitation will be the availability of sufficient engineers and skills to build the plant.

It may well be that part of our strategy should be to establish battery assembly in India.

There are other resources and technologies globally required for the energy transition. All of these require national strategic analysis, which is now underway.

Australia’s National Hydrogen Strategy is now four years old, but the consultation process on Australia’s National Battery Strategy has only just begun.

The government is clearly very busy developing strategies for the important industries on which our future will be based. Of course, these industries must all deploy the latest technology across AI, robotics, quantum computing and cybersecurity. But these technologies are a means to an end.

The disappointment is that our premier scientific and industrial research organisation placed such little emphasis on the lithium-ion battery supply chain constraints and regarded this as something merely to be “considered” rather than the critical priority action that it is.

Perhaps the next review the government needs to consider is of the CSIRO itself and whether it might be time for some serious restructuring, including undoing the merger of NICTA with the CSIRO and dividing up some of its other functions in ways that more closely align the organisation as a whole with key national priorities.

David Havyatt is a former telco executive, former adviser to Federal Labor ministers and former advocate on behalf of energy consumers. He is a long term observer of Australian innovation policy.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.