One of the certainties about politics is that the government should ‘control the narrative’. After all, it is the government that can make decisions of consequence; it can legislate, it can tax, and it can subsidise.

Successful oppositions are those that can seize control of the narrative. Tony Abbott was the absolute master of it, and he (or his advisers) distilled it into pithy three-word statements like “Axe the Tax” or “Stop the Boats.”

Peter Dutton is threatening to do the same over nuclear energy. Labor is in danger of repeating the mistake they made with the Voice, underestimating the effectiveness of Dutton’s position.

My primary evidence is an email from “Labor HQ” asking me to “sign our petition to say NO to Dutton’s nuclear plan”. The top of the email is produced below.

Otherwise, Labor has just resorted to derogatory comments about the cost of nuclear or the timing of its availability.

As a thought experiment, let’s take the question of nuclear power for Australia seriously. What would a policy to do that look like?

Many questions need to be asked about nuclear, but we can start with the big three. How much would it cost? How long would it take to build? Where would you build it? A threshold question remains about nuclear waste.

People forget that the ban on nuclear power was a Greens amendment to a Howard Government Bill. The Howard Government was legislating to build a second reactor at Lucas Heights; it agreed to the Greens amendment to pass the legislation.

Any plans to remove the current ban on nuclear power will have to address the question of waste. Admittedly, we may face this issue with our proposed submarine fleet, but on a longer timescale. There is no current solution to the issue of waste.

Let’s talk about the other elements. The government has relied heavily on cost as the basis for rejecting nuclear power. For costs, we must distinguish between traditional large-scale nuclear power stations and the so-called small modular reactors (SMR).

If traditional power stations are considered, opponents to nuclear cite the UK’s Hinkley Point C.

One of the reasons Hinkley is taking so long and costing so much is that it is a bespoke build. Even though a French company is working on a French design that is being built cheaper in France, the linked Spectator article notes that welding on the second French reactor is being completed four times faster than the first. That is, there is an experience effect.

As the article also points out, the costs are also a function of the approach to nuclear regulation. You can’t know what those costs are in Australia because we have no scheme for nuclear regulation.

Presumably, no one will commence a project until they know the regulatory requirements. Once the legislative prohibition is lifted, generating the regulatory arrangements is minimally a two-year project (if just to allow for the cycles of necessary public consultation) and presumably longer.

The Spectator article provides a good example of the issues covered concerning water intake and other environmental impacts.

We can reasonably conclude that traditional nuclear power stations are only viable if Australia built a fleet of power stations of the same design. That would need to be a government project, not a private sector one.

Dutton’s plan of using the sites of existing coal-fired power stations is possibly desirable both because of the existing transmission lines and water resources.

Those sites were primarily chosen because of their proximity to coal. In the millennium drought, we had coal-fired power stations offline due to a lack of water. So, the ideal location for nuclear power stations would be closer to more reliable water sources.

We then come to those mythical creatures, SMRs. They are mythical everywhere except for one instance in each of China and Russia. The supposed benefit of these reactors is that they are effectively mass-produced.

The UK government has poured money (210 million pounds) into Rolls Royce to develop them. Rolls Royce is, of course, the company the Australian government is providing with $4.6 billion over ten years to build the kind of small modular reactor that goes into an AUKUS submarine.

The fact is that no one can tell you the cost of SMRs. Though the ‘production line’ might eventually result in low costs, the first units will not be cheap. These units are small – often below 100 MW, but the IEA defines them as up to 300 MW. Rolls Royce design is slightly larger at 470 MW.

Consequently, you wouldn’t install them where the old coal-fired power stations were built. Firstly, there is a numbers question – you need somewhere between six and ten to replace a 2 GW power station (which is, admittedly, usually 3 660 MW units).

But more importantly, because they are small, you would locate them closer to load, just like the original coal stations were.

You then confront the whole question of community acceptance of the infrastructure. There is already resistance from communities that have tolerated coal power stations to having new nuclear.

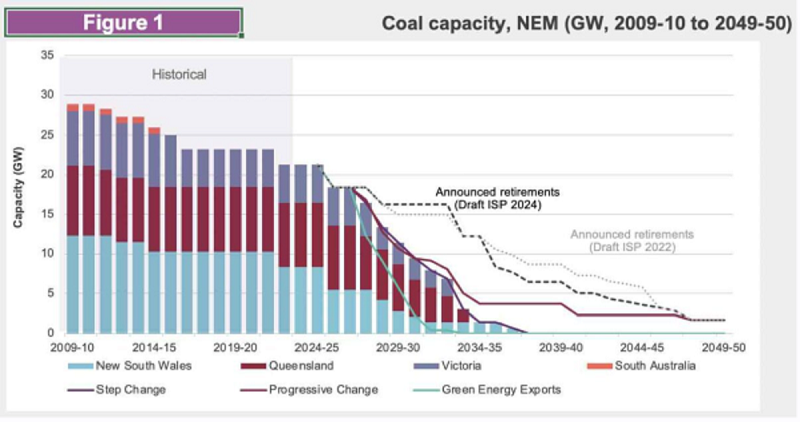

Finally, let’s address the timescale question. From a standing start, let’s assume four years to develop the regulatory scheme, two to complete the regulatory approvals, and four to construct the first nuclear power station. Call that ten years. AEMO is now expecting almost all the coal stations to have been retired by then (see chart below).

The reason for these retirements is the impact on the economics of a “baseload” generator of high penetrations of renewables – especially solar.

Coal plants need to keep generating and have minimum loads (the base load) that they need to keep generating. It is hugely expensive to start them and stop them. They can’t make money in the existing market structure.

No matter how much some people wish it were otherwise, nuclear power is not an option to replace the retiring coal power stations. The first units of traditional nuclear power stations or SMRs will be incredibly expensive, while solar, wind and storage costs continue to decline.

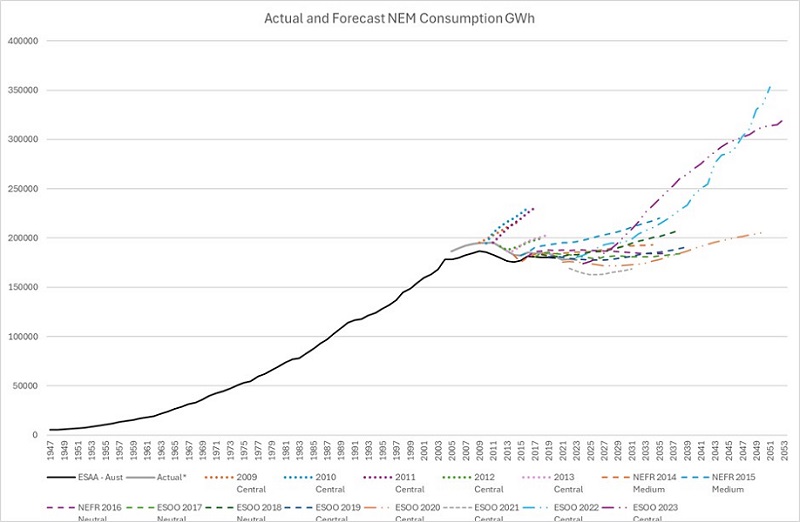

The story gets more interesting after 2034. The electrification of transport (liquid fuels) and process heat (gas) results in a return of consumption growth in the NEM compared to rates last seen at the end of the last millennium.

The solid black line in the chart below is the electricity consumed in all of Australia. The grey line and all the forecasts are for energy sent out for the NEM – so different coverage (no WA or NT) and before transmission losses.

Only in the last two years has AEMO’s plan genuinely addressed the consequences of net zero and electrification.

Meanwhile, fusion, which has been thirty years away for the last fifty, is likely to surprise everyone. When it becomes a reality, it will be suddenly available in five years. Australia’s stake in this, HB11, is particularly interesting as it isn’t a thermal plant; it doesn’t need a water supply.

In the US Congress has already moved, on the recommendation of the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission, to regulate fusion separately from fission.

It may well be that nuclear power plays a role in meeting the system’s demands to manage electrification. It becomes a tricky position if the alternative to nuclear is continuing to use gas.

As Realpolitech notes, having a mature conversation about the prospects of nuclear power is part of building public confidence that the plans for a green superpower are based on analysis rather than ideology or response to vested interests.

Labor’s better policy position is to lay out these cost and timing issues and undertake the necessary regulatory development to make nuclear an option post-2034. That preparation should include developing a separate regime to cover prospective fusion power stations.

David Havyatt is a former telco executive, former adviser to Federal Labor ministers and former advocate on behalf of energy consumers. He is a long term observer of Australian innovation policy.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.

A note from the author.

I should, of course, have mentioned the tabling in the Senate of the report of the Foriegn Affairs, Defence and Trade Standing Committee on the Australian Naval Nuclear Power Saftety Bill.

(https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Foreign_Affairs_Defence_and_Trade/ANNPSBills23/Report/List_of_recommendations)

It makes no difference to the argument. The low level waste from AUKUS submarines will be stored at naval baes while there is no plan for high level waste which is still a long time in the future.