Globally and at home, discussions about what the world will need to look like by 2050 are becoming ever more prevalent – the future of industries, the knowledge economy, and reining in global temperature increases are just a few of the critical topics.

Open economies like Australia’s are subject to major trends that are reshaping today’s global economy. These include major shocks like the COVID-19 pandemic, physical and transition risks of climate change, geopolitical tensions, increasing digitisation, and vulnerability of extensive global supply chains.

This external environment invites concerns that range from sovereign capability (can we meet our essential needs?) to economic prosperity (will our grandchildren have good jobs?) and more.

To address these concerns, governments around the world have taken different approaches in a common attempt to implement more integrated, modern industry policy.

Modern industry policy is a purpose-driven approach where governments implement an integrated suite of policies to signal and support industries in a particular strategic direction. Recent examples include the United States’ Inflation Reduction Act, its Chips and Science Act, and the EU’s European Chips Act.

This signals a shift in approach towards governments being more purposeful and directional about the economy, and the emergence of thinking that current circumstances can’t simply be left to hands-off economic philosophy.

Modern industry policies acknowledge that complex challenges demand complex responses, and that both governments and markets play key roles.

The Commonwealth government’s Future Made in Australia (FMiA) plans are a response to this global transformation – the biggest sustained economic transition since the industrial revolution. Their purpose? To secure Australia’s future economic base through investing in key industries and achieving national decarbonisation goals.

This is important considering Australia’s low economic complexity ranking worldwide, and government R&D spending being well below OECD levels. Australia must rethink its reliance on industries that ship natural resources overseas to be processed and get serious about seeding the future of purposeful and sustainable industries.

The government’s plans would bring together existing and new policies and ensure they are implemented in a more coordinated way. Success, however, would depend on how deeply the government can institutionalise this new approach – setting clear and focused direction, coordinating new and existing programs, and aligning public investments.

Until recently, the Commonwealth government’s forays into industrial policy have been mostly focused on investing funds. The Clean Energy Finance Corporation and the National Reconstruction Fund are key examples.

However, there is a question around whether this is the best, or indeed even a sufficient, approach. And if not, then what is the most effective way to deliver a purpose-driven approach to industry development?

Released in early April, the Centre for Policy Development report, Setting direction: a purposeful approach to industry policy, proposes an integrated framework which outlines three key areas for successful modern industry policy: directionality, policy mix diversity, and governance.

We are pleased to see that the details of the FMiA plans in the Budget 2024-25 align well with our framework. Accompanying this is the National Interest framework that will provide rigour to government decisions on big public investments.

Directionality

First, governments must embrace their position as a key player in the economy by setting a shared direction and leading a collaborative and coherent approach to achieving it.

A good strategic direction for a modern industry policy requires a small number of priorities or goals – any more than four or five is unrealistic to direct a whole-of-country effort.

These goals should be measurable, have time frames, and describe a precise end-state. Something like “12Mt a year domestic green iron production” rather than Net Zero industries.

They should avoid being so narrow as to only allow specific technologies or firms – “12Mt a year H2-DRI iron production” is likely too specific to yield ideal outcomes.

Before the FY2025 federal budget, the government had several initiatives for industry development that together made up over 30 different priorities, including the CSIRO missions and the foci of the Cooperative Research Centres (CRCs). This is much more than a few, precise goals or priorities that would help guide the country towards a specific direction for industrial development.

The FMiA plans provide direction on the priority industries that the government will support.

The National Interest framework has identified two streams for these priority industries: the Net Zero transformation stream, which includes renewable hydrogen, green metals, and low carbon liquid fuels, and the economic resilience and security stream, comprising refining and processing of critical minerals and clean energy manufacturing.

Focusing on replacing carbon-intensive incumbents through renewable hydrogen for example, makes sense. Research from the Centre for Policy Development (CPD) recommends investing in industries like emission-free iron, alumina/aluminium, and ammonia. These industries represent strategic comparative advantages due to Australia’s abundance of land and renewable energy potential.

It is less clear that industries such as solar panel manufacturing make sense for Australia and play to our comparative advantages. The key is to identify industries that will not need continued government subsidisation far into the future, well beyond the first movers start developing their supply chains.

It will be interesting to see how goals for the industries in the FMiA plans continue to be developed. Will they be measurable and include clear timeframes, or will they lack clear guidance?

Policy mix diversity

One of the key premises behind many modern approaches to industry policy is that transformative new industries need a diverse policy mix beyond just financial capital. The Commonwealth government knows it cannot size up to the scale of subsidies in jurisdictions like the US, EU or China, and needs to instead focus on leveraging Australia’s innovation system.

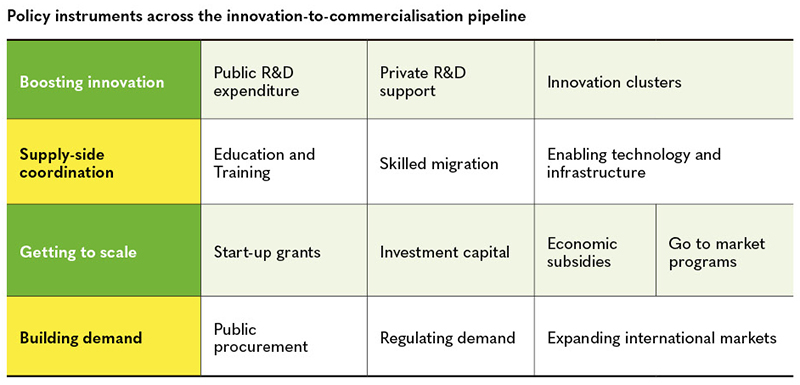

Policy tools need to support four components of the innovation-to-commercialisation pipeline. They need to boost innovation in new industries, coordinate the supply side, bring firms to scale, and build demand. Governments should spend time scoping their industrial goals, clearly identify the currently binding constraints, and prioritise a relevant diverse policy mix to resolve those constraints.

The details published about the FMiA plans so far show a clear recognition of the need for a diverse policy mix.

Alongside funds for economic subsidies, there is a role for regulation. The Government has pledged billions of dollars in funding to accelerate investment in priority industries. But it has also recognised the importance of strengthening approvals processes for priority sectors including for renewable energy, transmission, and critical minerals projects.

Apart from support for bridging the green premium for low-emissions products, there are funds for early-stage innovation, with production tax credits for renewable hydrogen, and funding for early stage development in priority sectors, including renewable hydrogen, green metals, and low carbon liquid fuels.

Another important policy ingredient is funding to ensure Australia has the information and technology environment to succeed and a sufficient number of trained workers. Millions of dollars are available for supporting the development of quantum computing capabilities as well as workforces with skills in clean energy, STEM subjects and the hydrogen industry.

These initiatives would be delivered through a coordinated effort including existing initiatives like the Australian Renewable Energy Agency and the National Reconstruction Fund.

Governments should be particularly attuned to policy interventions that create shared value – not just supporting a single firm or project, but creating resources, financial flows, or enabling infrastructure that supports many projects.

Governance

Mobilising broad swathes of the government and the economy in support of a strategic direction requires alignment across many actors.

Modern industry policy should aim to use the whole apparatus of government to encourage industry development. It is not enough for governments to simply set a target for their industry ministry when many important factors sit outside the industry portfolio, such as workforce development (education), research, business regulation, and more.

Instead, a central agency should take the lead: an agency with the ability to reach across portfolios and silos, and to more effectively compel participation and alignment from disparate parts of government. It is therefore encouraging to hear about plans for an FMiA Act to be overseen by Treasury.

Leadership by a central agency is generally not intended as central planning by the governments we have studied, but rather achieves several useful goals. It:

- Develops alignment and consensus regarding a government’s direction for industry policy

- Provides a forum to convene multiple government departments at a high level

- Creates a mechanism to engage and coordinate with industry/sector leaders

- Ensures alignment across a diverse policy mix

- Builds institutional capacity to effectively administer policies

Innovation agencies in turn would be essential to coordinate the skills, knowledge, innovations and investment needed for new industries. Examples include Innovate UK and Sweden’s Vinnova. They can stimulate collaboration between actors in the innovation system – companies, researchers, public sector and civil society – and seek to ensure their buy-in for relevant government initiatives.

The FMiA plans include funding to consult with industry, investors and major stakeholders to develop a “single front door” to improve coordination of major investment proposals. How this front door will evolve and who will administer are as yet unclear.

Conclusion

Modern industry policy requires governments to set strategic directions for new industries – articulating clear and specific goals around which to rally businesses and bureaucrats alike. Goals are most likely to be achieved when the whole apparatus of government is used to deploy a diverse and appropriate policy mix. Of course, aligning many government agencies – not to mention many governments at different levels – requires serious coordination and governance.

It is time for Australia to advance with a modern approach to industry policy that proactively responds to a changing global landscape, whether it is facing a great climate transition, building supply chain resilience, or planting the seeds for long term prosperity. We know the successful industries of 2050 will look very different to the successful industries of today, and it is great to see the FMiA plans advancing a big step towards a purposeful approach to modern industry policy.

Toby Phillips, program director for the Centre for Policy Development’s sustainable economy program. He works on policy ideas and partnerships to build a more environmentally and socially sustainable economy. Toby holds a Master of Public Policy from Oxford University and a BSc(Hons) in chemistry from Flinders University.

Esther Koh, program officer at the Centre for Policy Development’s sustainable economy and wellbeing program. She is completing a Master of Public Policy at Monash University and has a Bachelor of Communications from RMIT University.

This article is part of The Industry Papers publication by InnovationAus.com. Order your hard copy here. 36 Papers, 48 Authors, 65,000 words, 72 page tabloid newspaper + 32 page insert magazine.

InnovationAus.com would like to thank our sponsors Geoscape Australia, The University of Sydney Faculty of Science, the Semiconductor Sector Service Bureau (S3B), AirTrunk, InnoFocus, ANDHealth, QIMR Berghofer, Advance Queensland and the Queensland Government.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.