Australia is looking to rebuild its industrial base to achieve greater self-sufficiency in manufacturing. But we are seriously under-investing in creating the engineering and technology knowledge and skills that will be required to achieve this outcome.

The COVID-19 crisis has demonstrated that Australia has been well prepared with a substantial and sustained investment in health and medical research over a 100 year period. And this is to be celebrated.

There is, however, a substantial mismatch between Australia’s very high level of public investment in medical research and the very modest commitments to investment in industrial research that lie at the heart of the current phase of global industrial development.

Medical research has been driven through over 40 medical research institutes linked to strong university medical faculties. The Manufacturing for a post-COVID world (WEHI) was established in 1912.

Notwithstanding the formation of the CSIRO in 1920, initially to coordinate agricultural research, there is no parallel system of Advanced Engineering and Technology Institutes to drive research in building and maintaining Australia’s manufacturing industrial base.

Without this engineering capability, the challenge for building Australia’s industrial base is formidable, and perhaps insurmountable.

Currently, Australia faces both a public health and economic challenge due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The public health response has been widely embraced by the community but has also created a national economic crisis with a collapse in employment and output in many sectors. This has exposed the vulnerability of an economy reliant on the minerals boom.

If ever there was a “burning platform” for change, this is it. The health crisis has devastated the accommodation, food service and tourism sectors, whilst the minerals boom accelerated the decimation of the manufacturing sector and put off the need for fundamental industry adjustment following the removal of tariff protection.

In particular, the crisis has drawn attention to the fragility of international supply chains.

Industry economists have been concerned for more than 20 years that Australia has been losing its capacity to make things. This concern is now revealed as a serious gap in our industrial capability and capacity to “build a bridge”, in the Prime Minister’s words, to a “better, stronger economy” in the future.

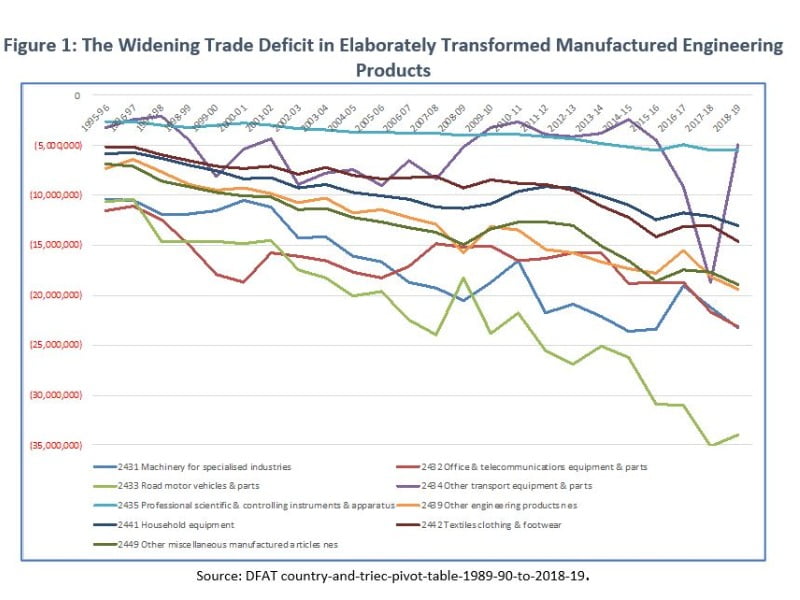

Australia’s imports of Elaborately Transformed Manufactures (ETMs) in 2018-19, at $214.5 billion, were more than double the value of imports in 1995-95 (inflation adjusted). Yet ETM exports increased by a mere $5.5 billion to $35.7 billion over this same period. This widening trade deficit is most acute in engineering products, as indicated in Figure 1.

While we may have increased some ETM exports this is overwhelmed by rise in imports. And with value of commodity exports flattening, and education and tourism vulnerable to external shocks, lifting domestic production and growing exports in manufacturing is now urgently required.

The crisis provides an opportunity to reinvigorate the economy around industries of the future.

Although definitions vary, these are generally taken to cover Quantum Information Science, Robotics and Artificial Intelligence, 5G and Advanced Communication, Visualisation, Autonomous Transport, Nanomaterials, Energy Capture, Storage and Transmission, and Advanced Manufacturing.

These areas draw heavily on knowledge and capabilities in Information and Computing Science and Engineering and Technology.

To date, the Federal Government’s policy response to the crisis has been mainly directed towards maintaining incomes and consumer demand, which will continue to suck in manufactured imports. This can only be a short-term response, particularly if the minerals boom begins to falter.

The Government has indicated that it is intending to develop a longer term strategy for manufacturing through a new taskforce. The task is becoming urgent.

Economic history clearly indicates that crises stimulate innovations in advanced technology and engineering. These innovations call on knowledge and capability created through public investment in the Science, Research and Innovation (SRI) system.

While Australia’s poor track record in this area has been well canvassed, the long-standing commitment to investment in medical research has proved an exception, and a useful one in the context of the current health crisis.

However, a mismatch has emerged between the high levels of public investment in medical research and the comparatively modest commitments to industrial research, particularly in the engineering and technologies that drive the industries of the future

The present crisis provides an opportunity to reinvigorate the SRI system and capitalise on new sources of growth. A quantum lift in investment in engineering and technology research will provide a foundation for stronger collaborations between industry research and public research.

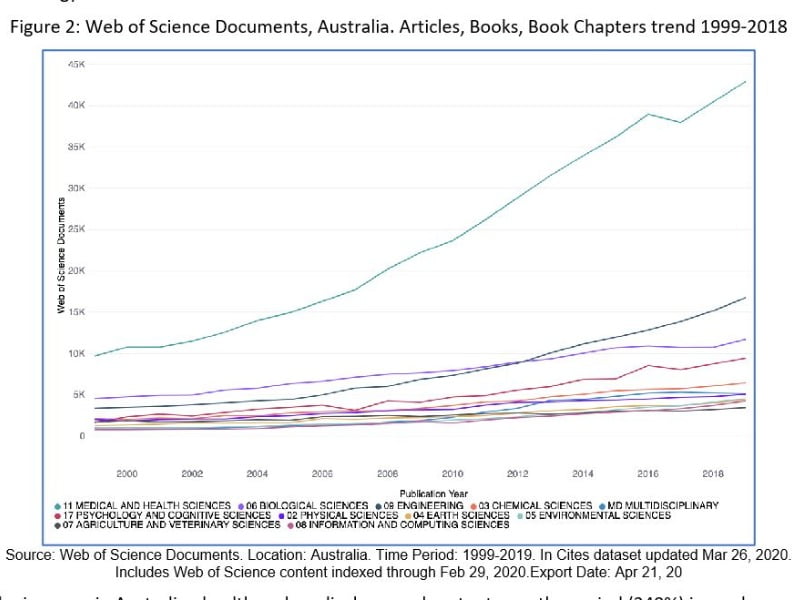

The effect of the concentration of public SRI investment in the medical and health research is shown in Figure 2 which charts Australian research outputs in 10 of the Australian two digit Fields of Research. It shows that over 20 years Australian medical research output increased from 9,685 articles, books, book chapters in 1999 to 42,672 in 2019.

This is 3.8 times greater than in Engineering, 10 times greater than information and computing, and 18 times greater than technology.

The increase in Australian health and medical research output over the period (340 per cent) is much greater than the world increase (95.9 per cent), which is quite remarkable. However, globally in 2019 output in engineering exceeded for the first time output in medical and health research, making Australia an outlier among advanced countries.

Health and medical research finds its way into medical and surgical procedures, manufacture of medical devices and pharmaceuticals, and most importantly in the current climate, into vaccines. Employment in health care and social assistance has grown by 23 per cent over the 2013-18 period, while manufacturing employment has grown by only 3 per cent.

Government commitment to medical research is maintained through a variety of channels. So is philanthropic commitment, reflected in the formation of over 40 medical research institutes that connect with university medical faculties.

Global pharmaceutical and medical device companies (including CAL and Cochlear) also form research partnerships with universities. But there is no parallel system of advanced engineering and technology institutes to drive research in Australian manufacturing.

CSIRO is the only public organisation with a specific commitment to industrial research and has provided leadership in many areas, such as material sciences, engineering, and data analytics.

It is also involved in a very broad range of industry sectors, although it would appear to be very thinly spread as its funding is continuously being cut. It is also required to cost-recover, which distorts both long term and short term priorities.

Internationally, university-connected advanced engineering and technology institutes are the foundation for creating the industries of the future. There are strong pockets of capability in Australia, but investment at scale is lacking.

A national commitment to engineering and technology must form the basis for industries that will add value in the post COVID-19 economy.

Australia has demonstrated that it is good at health and medical research and is providing imaginative and clever responses to supply chain gaps. Ingenuity is alive and well. But building the industries of the future that will lie at the heart of a manufacturing resurgence requires deep public commitment to engineering and technology-oriented research and innovation. We now have the opportunity to address this research-industry mismatch.

These issues are examined at length in the recently released UTS Occasional Paper Challenges for Australian Research and Innovation, Sydney, 2020.

John H Howard is a Visiting Professor at UTS, and Director of the Acton Institute for Policy Research and Innovation. He has been providing research, analysis, and advice in the area of Science Research and Innovation policy through his own consulting business for more than 20 years. John holds a PhD in Engineering from The University of Sydney, a Master’s degree in public administration and policy from the University of Canberra and an honours degree in economics from the University of Tasmania.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.