Australia needs a fundamental change in its approach to innovation and exports to capitalise on the government’s $1.5 billion Modern Manufacturing Initiative, according to the scheme’s chief architect Andrew Liveris, who says the federal policy should guide an overhaul of the national economy.

The former chair and chief executive of Dow Chemical, Mr Liveris this month warned of Australia’s worsening economic complexity numbers and decades of innovation policies which had failed to prepare the country for a more digitised, sustainable and competitive world.

Mr Liveris said while the nation had fared well in handling the pandemic and is still among world leaders in wealth rankings, Australia currently lacks “sufficient innovation and ambition” for a fast-changing global market and geopolitical disruptions and may have become “complacent”.

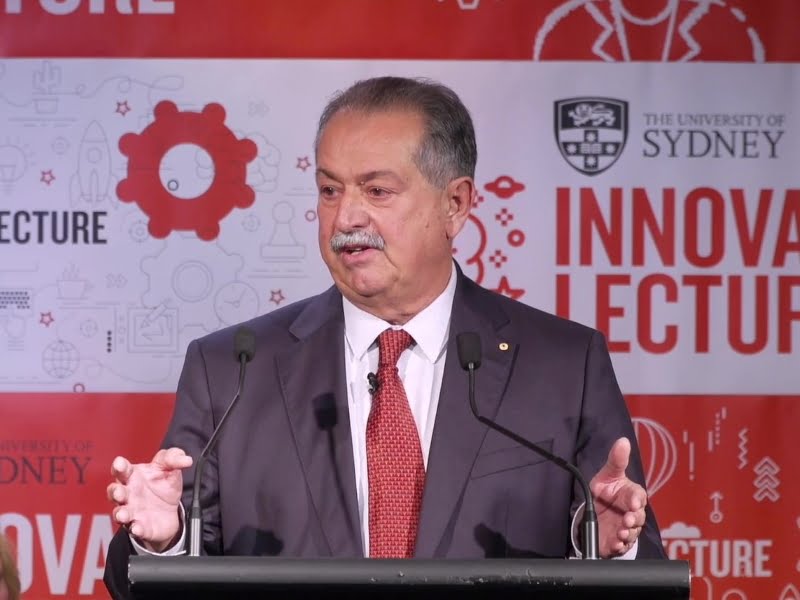

“I am concerned about our appetite for innovation and entrepreneurship,” Mr Liveris said at the University of Sydney Warren Centre for Innovation Lecture earlier this month, where he urged stakeholders to “reset the Australian economy”.

Mr Liveris advised both the Obama and Trump administrations on manufacturing, and was a special adviser to the Australian Government’s National COVID Commission Advisory Board last year, which led to the government’s “gas fired” pandemic recovery plan, subsequently endorsed by Mr Liveris.

At the University of Sydney innovation lecture earlier this month, he called for the building out of ecosystems based on successful models in Ireland, Luxembourg, Canada, Israel and Singapore, where long-term, bipartisan innovation policy fosters strong pubic-private partnerships, supports R&D and manufacturing hubs, and ultimately leads to higher commercialisation of IP.

In successful foreign innovation ecosystems, public servants also moved quickly and avoided outsourcing work wherever possible, as part of a broader focus on building skills in areas in need, he said.

But in Australia, policy had been uncoordinated and the economy is dropping in complexity while the startup sector continues to struggles, he said.

“Our largest customer [China], to whom we sell 40 per cent of out products and services is now choosing to buy its coal, barley, seafood, wine, tourism and education from our competitors. Iron-ore, which is said to be of comparable quality to ours will soon be available from Sierra Leone.

“It is reported that our national debt is expected to rise to almost a trillion dollars by 2024/25. We have high energy costs that materially impact the competitiveness of our manufactures. And we have a skills mismatch between the public and private sector after decades of outsourcing.”

He added Australia’s global brand in business culture is “almost non-existent” and Australia’s “place in the world continues to slip”.

According to Mr Liveris, Australia should learn from the countries which had built strong export markets without natural resources, and from resource heavy nations like Canada which are actively diversifying their economies.

To join them, Australia must show some “humility” and urgently reshape its economy by focussing on priority sectors and their ecosystems in a more holistic way built around domestic manufacturing and processing.

“We seem to have overlooked the fact that if we own production, we own research and development. And if we own research and development we own the products. This then becomes our competitive advantage,” Mr Liveris said.

“Manufacturing then becomes a capability and modern manufacturing becomes an ecosystem. And, as every engineer will tell you, the ecosystem of manufacturing is from research, to prototyping, to production, to scaling, and selling and designing the prototype for the next product, which then gives you the next research project.

“And yet we haven’t invested in building competitive advantage in enough sectors. Nor have we invested in building the ecosystems because we have insufficient production capability in Australia.

Mr Liveris chaired the taskforce which developed the federal government’s $1.5 billion Modern Manufacturing Initiative (MMI), which allocates large grants to manufacturing projects in six priority sectors and requires co-investment from state governments and the private sector.

“[The MMI] is an important first step. The recommendations are challenging and require Australia to apply a sharp focus on outcomes and take more informed risks with the money taxpayers commit every year in the name of innovation.”

Mr Liveris said the MMI is not simply about more spending and provides a “path to progress” for Australian innovation and will lead to more “informed risks” on innovation spend.

He called for the establishment of a MMI board with long term bipartisan support to make the decisions and connect stakeholders.

Mr Liveris said taxpayers already spend up to eight billion dollars each year funding innovation programs and there has been a steady stream of innovation prepared for the government, but initiatives had lacked an overarching strategy and were distributed to widely across federal portfolios.

“This approach delivers way too little. The reports have to end and the effort needs to shift to delivering stronger outcomes. The strategy must become delivery.”

He called for focus to shift to areas like space and critical minerals, saying there is a multibillion dollar opportunity for Australia in refining lithium alone, rather than exporting the raw material. More refinement in Australia would also help lower emissions by using cleaner domestic processes, according to Mr Liveris.

The same approach can apply to agriculture, Mr Liveris said, with food product processed on shore, and eventually a more circular economy developed.

But to achieve it Australia needs to “very ambitious” and address its continued slip in global innovation rankings.

Mr Liveris, who has worked with governments since 2004 said the COVID-19 pandemic created the catalyst to make fundamental change.

“Because of global events we’ve made more progress in the last 12 months than we in the last 17 years.”

It is a rare opportunity for Australian industry – which he estimated is at an Industry 2.0 level – to leapfrog other advanced economies into “Industry 5.0”.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.

Check out my book Innovation in Australia Creating Prosperity for Future Generations at http://www.innovationinaustralia.com.au.

By any criteria Australia’s performance over many indices is mediocre! Economic Complexity is only one! There was a time when Australia talked about global competitiveness, best practice and benchmarking – it was TOO hard and we retreated to inaction -then we proudly announced we had made the transition to a service economy allowing us to wallow in 29 years of economic growth – where is the evidence Australia has the WILL to engage in such ambitious thinking?

This is a liminal moment and there is no URGENCY that I can identify! Check out my book Innovation in Australia where I have proposed a pathway.

http://www.innovationinaustralia.com.au

Our competitive advantage is our large land and sparse population. We should work with similar countries to develop tech which serves that demographic, such as Brazil, Mongolia, South Pole, South American and African countries. We should ideate the kind of smart devices and processes needed for survival in isolated locations, and how to build and repair them ‘in situ’. Our main economic sectors are financial services, health and education, so lets leverage manufacturing goods which can be deployed in remote locations and are mobile. e.g. scanners, shared devices for teaching and communication, mobile ”da vinci” style operators for medical procedures, and other items which help for isolated peoples. The future of specializing in this realm, is that this tech would then be valuable in space, at polar stations, underwater facilities- global maritime operations etc. Our uniqueness is what we should build upon, and not worry about competing with the big urban markets with different, already well serviced innovation ecosystems.

No one wants to talk about reforming the system or even to admit that it has any real basic structural problems. Any such admission will obviously reflect on the people most closely involved in the existing structure.

This of course is the first and most basic problem associated with any innovative project. Innovators banging on the door and seeking an audience to outline any new proposal. Just talk to anyone who has tried.

Our innovative ecosystem has been out of focus and looking in the wrong direction since it first began. i.e. Looking at the teams touting the idea at the expense of the idea.

The slogan being “A good team obviously means a good idea and more likely that the idea will succeed. Lets now train the team to become good business developers of the idea.” Surprise, surprise. Innovators are not good business people. No matter how you train them. Even if they developed a good model, committed and delivered a good pitch.

Have a good look at the Israeli model. They have an independent group take a close look at the idea from ALL aspects almost ignoring the team or the innovator. This includes R&D, manufacturing etc. etc.

The originating team is almost sidelined by this time………Probably developing a new innovative concept.

Innovators I suggest, by and large, make bad business people. Its not their natural skill set. No matter how long and hard you try and retrain them into business people. Recruitment, marketing, communication, supervision etc. etc. are the essential ingredients of business people.

Its time we learnt this lesson.

Innovation and entrepreneurship are not hand in glove concepts. Nor are innovators and entrepreneurs identical personalities having identical natural skills.

I hate to say this but I feel we may have to re assemble our whole ecosystem. Instead of trying to build new businesses with unskilled and unsuitable people we try and assist existing businesses to re invent themselves with new and innovative ideas.

Many have done this transformation themselves recently but the time has come for all of our now separated bits to combine to revitalize our existing manufacturing capabilities.

Just a few thoughts, off the cuff, from a well and truly frustrated innovator. (Who does not want to become a business man.)

Google “crying for innovation:ship crunch”.

Great summary Joseph, of Andrew Liveris’ call for a much needed overhaul.

“In successful foreign innovation ecosystems, public servants also moved quickly and avoided outsourcing work wherever possible.” True, the Public Services in Australia has outsourced ( mainly to the big five foreign owned consultancies) almost all technical and policy capabilities to such a degree especially in Canberra ( where the PS is the main game in the town) that the PS is isolated from industry. Most PS’s have no worked experience with actual industry and entered the public service for long term careers, perpetuating a PS culture that is concerned with upward management that does not now relate to industry, manufacturing and its needs.

“This approach delivers way too little. The reports have to end and the effort needs to shift to delivering stronger outcomes. The strategy must become delivery.” So true, as is the example of refining lithium.

There is the urgent need to examine funding for Centres that have not delivered outcomes and replace funding to PPE’s that will deliver project not reports.

What Andrew Liveris is recommending is reassuring as it represents what has been recommended by many commentators to governments over many years. Back in 2015, I had my two bob’s worth! https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/transforming-our-economy-from-innovation-open-angus-m-robinson/ noting the need to establish an economic development board!