Australian government approaches to technology have defaulted to two over-riding themes: delivery and efficiency. The lack of progress – and of transparency around activities, expenditure, or accountability – suggests a lost decade or so in technology in the Australian government.

To help understand how that happened, we start with the last major effort at reform of government ICT, the 2008 Gershon Review. That then allows us to think about what government ICT, beyond simply service delivery, might look like.

That the Australian Government has struggled with its own technology has been apparent for some time. The last major review of whole-of-government ICT was undertaken in 2008, by former British civil servant, Sir Peter Gershon, in the early days of Labor’s last time in power.1

In his review, Gershon observed that Australian government ICT suffered from ‘weak governance’ at the whole-of-government level. That, coupled with ‘very high levels of agency autonomy’ had led to sub-optimal outcomes in terms of prevailing trends, financial returns and the aims and objectives of government.

It is dispiriting to consider how little has changed. In terms of Gershon’s seven key findings, over the years there have been some measures to address concerns. Typically, these have fallen short or been wound back.

For example, funding was stripped from agencies for Gershon’s planned reinvestment fund, but those returns were never realised, lost in the Budget process – during Labor’s own last term. The Digital Transformation Office created a digital marketplace, its operation subsequently attacked by the Audit Office. Efforts to manage the use of contractors have been lost through the imposition of APS staffing caps under the last Liberal/Nationals government.

Indeed, there is an argument that the last 10 to 15 years represent a lost decade in terms of Australian government technological capability and capacity. It’s clear that there are deeper impediments to change and the prospect of better outcomes, than those identified by Sir Peter.

Before diving in, it’s worth recognising that the picture is not uniformly dark. Those working in technology inside government tend to the optimistic – the opportunity to build, to see new ways of doing things, is often what attracts many to ICT, and many are motivated, too, by the mission of public service.

As in any sector, there are good leaders to be found. And there have been successes, often not the programs that attract attention, but the slower realisation of capability.

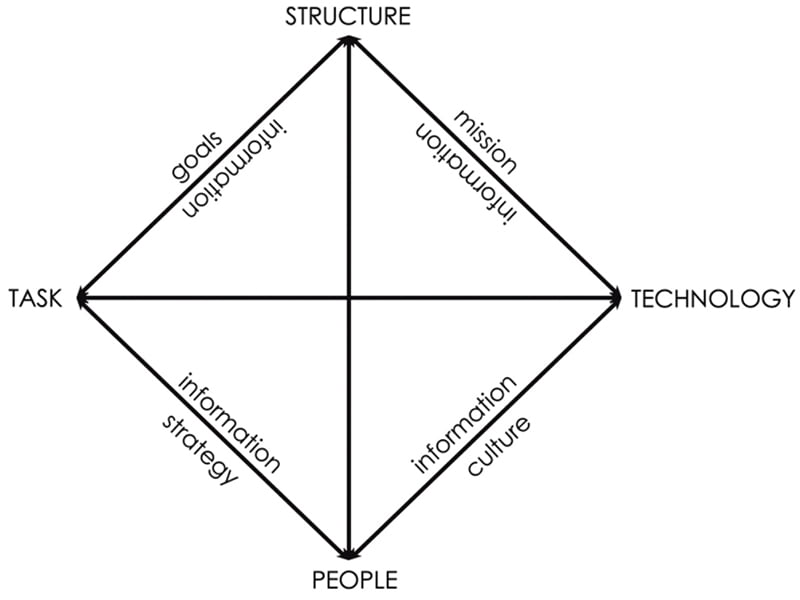

So, what are the underlying drivers that are apparently inhibiting good ICT performance within the Australian government? Let’s take a comparatively simple framework to help assess the challenges: Harold J Leavitt’s 1965 model for change.

Set out below, Leavitt’s Diamond is comparatively well known; more importantly, it recognises the interdependency of and dynamism between people, technology, task and structure.

The Diamond’s core idea is that for the organisation to be effective, each element needs to work with the other elements. Naturally, there are further complicating factors, notably regulatory requirements, political imperatives and financial constraints.

Nonetheless, for technology to deliver on its promise, the APS needs to adapt its structure, ensure fit with task, and have all its staff properly equipped for designing, developing, managing, and using technology. It also needs to ensure that the technology it employs is appropriate to the task, the business of government, and by extension, to the citizens of Australia.

In this light, the shortfalls in the Gershon Report become apparent. His terms of reference preclude considerations of structure, aside from an assessment of the role of the Department of Finance, or ‘a similar central body’, contributing to the use of ICT across government.

Instead, Gershon focussed on governance and financial means of control – much of which has been eroded or neglected in the intervening years.

Gershon identified the need to improve skills in the Commonwealth – the people element of the Diamond. He focused on deepening the well of expertise, primarily through limiting the use of contractors and building better career progression for APS staff.

But digital technology has come to imbue every aspect of government business and so to be effective requires more than a narrowly defined ‘profession’ of ICT staff.

Gershon, concerned with the efficient use of technology, focused on infrastructure – data centres and communication networks – and enterprise systems. He had little to say about software, data and digital.

Consequently, as data and digital have drawn policy-makers attention, the importance of Gershon has faded over the years.

He also said little on strategy, culture, mission or purpose – all factors that help manage the interactions between people, task, structure and technology – aside from the need for an overarching whole-of-government ICT strategy, a task he assigned to his recommended governance bodies.

It’s hard to get a grip

The Gershon Report’s limitations are unsurprising, given the terms of reference. Leavitt’s Diamond can also be used to help understand why his recommendations failed to stick.

The federal government is essentially a federation of competing power structures. Departments compete between themselves for resources in the Budget process, for attention in the Cabinet process, and their officers in the pursuit of ambition.

A range of factors, including political, governance and an increasingly incoherent Budget process, have given greater weight to policy initiatives rather than resourcing effectively existing infrastructure, programs and applications.

Departments and agencies have become increasingly dependent on new policy proposals through the Budget process for everyday operations. That includes the sustainment and management of existing ICT, not simply new technology supporting new initiatives. And so, competition for funding has intensified.

Departments often consider the affordability of their technology stacks. But the decision to outsource – whether to the private sector or to other departments – is not necessarily a cheaper option. And it may impose other disincentives, including a loss of control and of responsiveness to ministers, an erosion knowledge and capability, and limits to internal flexibility.

Realistically, the ability to outsource or share the burden may be limited. There are some applications that are commodity or common to all agencies – Microsoft’s Office suite, CabNet, corporate enterprise applications.

But many applications are unique. There are no other agencies able to deliver the Bureau of Meteorology’s forecasting services, for example.

Government ICT is not easily standardised – it contains a diverse and constantly evolving mix of applications, technology, skills and needs.

Even so, government structure and the process of assessing, prioritising and allocating resources have frustrated a coherent view of government ICT.

People

The pressure to deliver government priorities, many of which relied on ICT, whether for collection, analysis, or interaction with people and companies, drove high levels of demand for ICT staff.

That need, already under pressure within the APS, intensified when the Abbott Government instituted caps on APS staffing levels.

Consequently, departments, under pressure to deliver, often lacking specific or sufficient staff with requisite skills, and with access to short-term project funding through new policy proposals, turned to contractors and consultancies. Increasingly, they have come to rely on them for everyday operations.

As that dependency has grown, the principal-agent problem – how does the principal know that the agent is acting in the best interests of the principal – has become acute.

Typically, government relies on the contract to ensure that the work it outsources is undertaken. But when a range of specialities, including procurement, legal advice, and even contract management, has also been outsourced, the oversight and reins of control become quite loose.

Further, the knowledge associated with problem scoping, design and the shaping of the contract are not retained within the department.

Once work has been agreed, knowledge and expertise asymmetry are often perpetuated. APS staff tasked with managing the contract may lack the technical understanding to properly manage performance and decisions made by the contractor.

They are typically reluctant to challenge the contractor even under the terms of the contract; doing so can be seen as disruptive, and especially where personal relationships have been established between partners and senior APS staff and ministers’ offices.

Government needs to find a way to break out of the vortex of outsourcing and escalating costs. In good part, the APS’s contractor problem is one of people leadership, management, and support, and of how the funding model shapes technology programs.

It is too late, now, to simply return to Gershon: more, and deeper change, is needed.

It may be worth returning to a nation-building ethos within the APS. That was the case for economists in Treasury, many who would then move on to the banks, pilots in the Air Force, who later supported the national carrier amongst others, and currently within cyber security, as they move through training in the Australian Signals Directorate.

That said, it’s also evident that the APS’s more recent efforts to create skill sets in digital and data are wanting – they needed a larger vision and better support.

Nor do those efforts address the lack of understanding of technology and its implications across the APS, from policy to contracting to finance and client support, and especially in decision-making and policy frameworks.

Technology

The APS lacks a concept of technology that is other than utilitarian, a cost centre, or delivery mechanism.

It’s a delivery vehicle, a means of doing things to, or for, others – the community, companies, even individuals. As such, it is primarily transactional – deliver this service, collect this data, interact with that person.

In resourcing terms, it is understood primarily as a capital block that must be purchased for a specific purpose and then depreciated over time.

The human element – people needed to design, build and deliver projects – are treated the same way. Retaining skills and knowledge beyond the life of narrowly defined projects, even as the technology and needs morph and change, is hard.

Yet, even with such a limited approach, gaining Cabinet agreement to technology projects is slow and arduous. It can take a year or two to get through the Budget cycle – in some domains, that’s two to four technology cycles, if not more.

Once agreed, departments may be held to delivery against original intent, often defined in detail. Large projects may revisit Cabinet several times, for separate tranches of funding, generating considerable process and political overhead, uncertainty, and a reluctance to change and adapt.

As departments’ operating budgets erode, funding of even core maintenance, upgrades and sustainment must be attached to ministerially supported, and thus politically attractive, policy proposals to make it through the Budget process.

That adds fragmentation and technical complexity. Each proposal often introduces new systems layered on old, rather than addressing the less politically attractive modernisation needs of government.

Thus, successful proposals tend to favour the big, slow and expensive, such as the overhaul of the welfare payments system, the ‘Global Digital Platform’ visa processing system, or the ongoing efforts to standardise a Commonwealth ERP, GovERP.

Alternatively, they are short, sharp, and shiny, where costs can outweigh the benefits, such as the COVIDSafe app and the Digital Passenger Declaration app.

A Budget process that allows political compromise in the moment offers limited scope for ongoing, post-decision learning, adaptation, and evolution in response to either technological change or user needs. And over the years, a bricolage of architecture, standards, systems, apps, vendors, skills, and capabilities has emerged.

Internally, the work of the APS has been comparatively inured from much of the disruption wrought by technology in other sectors, industries, and professions, but what change that has occurred has not been overwhelmingly beneficial.

For example, clarity over decision-making, accountability, and influence, and compliance with record-keeping requirements, is harder as ministers and their staff use peer-to-peer encrypted apps.

The urgency of government business is exacerbated by social media, lessening patience with more considered analysis.

Security remains a constant, growing and typically underfunded characteristic of government systems, as evidenced by ANAO findings.

And the propensity for organisational amnesia has increased as unwieldly document management systems and reliance on unstructured data substituted for hard copy and records and knowledge management staff.

Given those structural and cultural impediments, it’s not surprising that government finds it hard to conceptualise, design, develop and use technology effectively. But, as mentioned, the picture is not uniformly dark.

Some of the modernisation efforts in departments, often funded through broader policy initiatives, have yielded positive outcomes.

Other initiatives, such as the Employment/Education Shared Services model, have gained traction through persistence and adaptation, while the ATO is applying systemic design precepts as a means of grappling with the complexity of its task.

Task

There is no unifying vision of technology across government, or of how government itself can evolve to best harness the digital revolution underway. Because resourcing is project-based, supporting targeted initiatives, the task assigned technology focusses on program delivery, efficiencies and transactions.

Consequently, the APS has adopted a pragmatic, small target approach to technology, as illustrated above: bundling funding into larger initiatives, relying on outsourced ‘on call’, albeit expensive, human capability, and leveraging existing technology stacks, and outsourcing short-term initiatives to preserve core functionality.

Despite the parsimonious view of technology as a cost centre, there remains an inherent assumption that government business can be reduced to data, algorithms and systems, and importantly, undertaken more cheaply.

That has two consequences. First, the natural, social and economic world need to be made, in James C Scott’s term in ‘Seeing Like a State’, ‘legible’2 – arranged in ways to make the task of governing simplified, standardised, and able to be reduced to manageable data sets.

That project is already well underway within government in the systems run by Human Services, Home Affairs, and the Australian Taxation Office, and on platforms such as Google, Facebook, and many others, less prominent.

Second, a government reduced to software is, in theory, highly malleable and manipulable – that is the nature and power of software. The question then arises as to how such a government operates in and supports democracy.

As Scott illustrates, too often those imposing legibility do so for the purpose of control, with highly injurious consequences. And as anyone who works in cyber knows, it exposes government even more to the vast range of vulnerabilities inherent in digital systems.

As argued elsewhere, the task of government involves three roles: stewardship, sense-making and shaping. Reducing technology programs to primarily goals of service delivery and efficiency overlooks these roles.

Indeed, often the elements of stewardship – transparency, accountability, and governance – are considered detrimental to speed and efficiency.

Much transparency around government processes, ICT expenditure and project outcomes has been lost in the years since Gershon, making it difficult to draw verifiable conclusions around the efficacy and value of government decisions and the allocation of taxpayer resources.

Considerable work is needed by government to retain trust in a world of disruption and disinformation, and to inform debate and generate more robust outcomes for the public and in national interest.

Increased transparency and accountability are necessary steps – technology can assist through providing access and analytical tools for the public and researchers.

Time and resources, too, are needed for informed, responsive consultation, the sort that underpins substantive, sustainable policies rather than ephemeral quick fixes.

Technology can help, but not supplant, the human-to-human interaction and repeat effort needed to call on, listen and engage with small business, individuals, community groups and not simply the large corporations accustomed to dealing with government.

That work assists with sense-making. In a world of rapid change in the technological environment, the Australian Government needs a better understanding of digital and emerging technologies, how they may affect the needs of its citizens and the opportunities presented by new economic models and the challenges posed by increasing geopolitical competition.

At the wavefront of all technological evolution, much is learnt by doing. That’s especially powerful with digital technologies, because of the cheapness and fungibility of software – much easier, faster and cheaper to simulate in a digital system than to build and test the physical analogue.

Importantly, digital technologies are general purpose technologies – they underpin or support many, if not all other, areas of technological development. Being good at digital technologies and their use helps support other areas of technological development.

Outsourcing the ‘smarts’ to external vendors and contractors does little to build capability and knowledge within the Australian government and limits the government’s own nation building capacity. In short, to undertake its task, it needs a better sense-making capability, much of which resides in knowledgeable and capable people, but that can leverage digital systems.

Last, the shaping task of government is much more than the simple transactions associated with collection of taxes, distribution of welfare, and monitoring of both populations and individuals.

Government policies, activities, regulations directly impinge on people’s lives; given its coercive nature, government has a responsibility and duty of care above and beyond that of the technology platforms.

Adopting Estonia’s near inviolability of the individual’s right to their own data, for example, would drive a rather different approach to the application of digital technologies.

Better stewardship – including the strategic thinking around how best to leverage limited government resources – and the sense-making associated with understanding technology would improve government’s shape-making, the development and implementation of policy and programs.

How can we do better?

So how can we realise a better approach to government technology – and by extension, improved democratic government?

First, more of the same – structurally, personnel policies, mindset, purpose – will most likely only reinforce deep systemic issues. Nor would it build the necessary intellectual, policy, program and technical muscle needed within the federal government.

A disruption to current thinking and approaches is needed. It’s clear, too, that any solution, to warrant likely success, must address structure, technology, people and task.

Last, because of the pace of change, and the nature of digital technologies, a solution is not ‘fire and forget’. It is ongoing, requiring heavy lifting and constant engagement – a journey, not a destination.

It must have the means to adjust and evolve in response to the drivers of digital change: accessibility, availability, affordability and speed.

That means that government needs to develop and apply a more sophisticated understanding of its role, purpose and functioning in a digitally enabled democracy, one that moves beyond simply the delivery and efficiency paradigms that currently dominate its approach.

A compass direction – purpose and values – is as important as a sense of the map, not least as the terrain will shift and change.

Thus, we propose a new entity, one that encapsulates the digital environment both within government, but also across society and the economy, and answers the question of what it means to be a digital democracy.

It must be a central agency with its own Cabinet minister and remit, and a funding mechanism that reaches across and shapes ICT in portfolios.

Such an entity does not currently exist. Nor, by definition, does it reside in any of the current departments or bodies.

Moreover, its functionality, conceptual approach and mindset do not currently exist, independently or inside current departments and agencies.

Even departments and agencies that aspire to a whole-of-government approach come with the conceptual and cultural baggage of their founding ethos.

Home Affairs, for example, sees itself fundamentally as a national security agency. Finance is interested primarily in expenditure and efficiencies. The Digital Transformation Agency has been crippled by a lack of both vision, limited to looking inwards, and remit.

Aside from the stewardship, sense-making and shaping of a digital democracy at the national level, another role for such a new entity would be strategic management of government ICT.

Government ICT needs a whole-of-government strategy, architecture, and standards, to enable change, flexibility, and responsiveness.

Lessons could be taken from the wholesale/retail model of platform and applications being implemented in agriculture, for example—there is scope to learn from those doing the technology now.

Control over funding, and better financial models, will be critical to the success of a new entity. We’ve illustrated above and elsewhere how funding mechanisms shape outcomes in technology design, choice and implementation. Funding will be key to rebalance contractor dependency.

Technologists are attracted by opportunity and innovation, and the chance to build new and better systems and applications. The new entity should have an innovation lab and sandpit, and one that is testing what works not for government, but for democracy.

A fascination with technology will only get a new entity so far: good leadership and management matter.

And because of the pace of change, and the expanding wavefront of new and emerging technologies, the new entity will need adequate, and dedicated, funding and support for education and training, and a flow of talent between the public service and other sectors in the economy and society.

Outreach, and supporting community groups researchers and think tanks, is another role – both digital democracy and government ICT are civil society issues, and fundamental to building democratic resilience in a technologically competitive world beset by authoritarian powers.

Such sustained engagement and interaction adds value, and allows the stress testing, including for security, of government systems, thereby supporting openness and trustworthiness on all sides.

It would help build the people and skills capability Australia needs around digital technologies, and their intersection with policy, society, the economy and national security.

Last, such an entity needs to take responsibility for the civilian side of cyber defence and capacity. Over the last 30 years, considerable weight has been given, deservedly so, to the national security aspects of cyber.

There needs to be a balance, and for the sake of democracy, a civilian capability focussing on norms, individual rights, economic outcomes, strategic thinking, and institutional and national resilience.

Conclusion

The government has the opportunity to learn from the past; doing so will better prepare it and Australia to adapt and, as best possible in a rapidly shifting, disrupted world, anticipate the needs of the future. That necessarily entails a step change to break from the current systemic pathologies.

Space, structure, determination, capability, and sustained effort are needed to realise Australia as a successful and resilient digital democracy.

And Commonwealth government ICT is core to that ambition. The government needs to understand and realise the use of ICT and digital technologies for more than just delivery.

Dr Lesley Seebeck is an Honorary Professor at the Australian National University. She has extensive experience in strategy, policy, management, budget, information technology and research roles in the Australian Public Service, industry and academia. Dr Seebeck has worked in the departments of Finance, Defence, and the Prime Minister and Cabinet, and in the Office of National Assessments, as well as in IT and management consultant in private industry, and universities.

Footnotes

- Gershon, Sir Peter (2008). Review of the Australian Government’s Use of Information and Communication Technology, August 2008, Commonwealth of Australia.

- Scott, James C (1998). Seeing like a State, Yale University Press.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.