COLUMN: Just a month and a half after this columnist raised the question of the future of Australia’s energy exports, the poor prospects for Australia’s coal industry have just become worse. On top of the climate change commitments from China and Japan, any hope that coal exports could be diverted to developing economies building new coal plants took a beating.

In May, US climate envoy John Kerry told the House Foreign Affairs Committee talks with China grew “very heated” over China’s continued insistence on financing coal-fired power plants around the world. Last week, Chinese President Xi pledged to the UN General Assembly to end the financing of new coal power plants overseas. This follows the decision in May by the EU and G7 (which includes Japan) to stop financing coal projects.

Sri Lanka is now the latest country to announce it will cease building coal-fired power plants.

The mainstream media has now noticed the need to fill the export void, with The Sydney Morning Herald reporting “It’s a $50b-a-year export industry. How long until coal’s rivers of gold run dry?“. The Australian carried an exclusive report that the PM is “preparing an integrated climate change plan to more swiftly transition Australia’s energy exports from fossil fuels towards new low emissions technologies” to avoid the nation being left behind.

These comments followed rapidly behind a misreported speech by Treasurer Josh Frydenberg, which did not so much address the need for a net zero goal as the need to factor in financial risk from climate change. Commentators must remember that even the aspirational Paris goal of 1.5 degrees warming entails further actual climate change. Net zero, therefore, doesn’t remove the risk; it just reduces it.

The Prime Minister’s newfound climate ambitions had their first outing in Washington after the Quad leaders meeting. As reported here, the Australian government has agreed to map the supply chains of critical technologies and materials, including semiconductors, as part of an agreement with fellow Quad nations on technology development, governance and use.

In his remarks after the meeting, Morrison said:

More broadly when it comes to climate. Today, there was a real sense of resolve and not just about the if question, of course, is the answer to that question, but the how and how we could support the particular developing countries within the Indo-Pacific to get access to the clean energy technology that enables them to transition their economies, just like Australia is seeking to transition our economy. An important initiative for a clean energy supply chain summit to be held next year in Australia to put together a road map over the next 12 months that could see how we can combine the best scientific knowledge, industry knowledge and academics coming together to ensure we can transfer our energy technology, clean energy technology, supply chains that support it to transform the economies of our region.

He added specific comments in relation to what he called “critical minerals”:

On critical minerals, Australia is one of the biggest producers, but we believe we can play a bigger role in a critical supply chain that is supporting the technologies of the future and further initiatives there today being led by Australia, but connecting up with the manufacturing and processing capabilities and end users in the United States and India and in Japan, as well…

There was a deep appreciation from all the Quad leaders today about the role that Australia can play in providing critical minerals into the region, because that is a necessary supply for the many industries and processing works that they operate themselves, whether it’s in the defence industry. Lots of discussions today about semiconductors and their role in the future. And this is an ecosystem we want to create and we want to do that as like mindeds in the region. And we want to create that so we can provide those supplies throughout the Indo-Pacific because remember, the Quad is all about positively contributing to the economic development, the prosperity and the stability of the region and very practical discussion on those items. We’re really good at digging stuff up in Australia and making sure it can fuel the rest of the world when it comes to the new energy economy.

The Prime Minister’s new buddies might want to look at his recent record on partnerships, and this is not a reference to the French and submarines. For example, in 2020, the government told researchers at two of Australia’s leading universities it would break a commitment to fund the Australian-German Energy Transition Hub. This partnership had been announced in 2017 by then prime minister Malcolm Turnbull and German chancellor Angela Merkel as a collaboration that would “help the technical, economic and social transition to new energy systems and a low emissions economy.”

The comments about critical minerals covered semiconductors. There are many compounds that can be used as the base, but the main base critical elements are silicon, germanium and gallium arsenide. Depending on the base, many other elements are used for doping. Austrade two years ago mapped the supply chain for critical minerals used in the US.

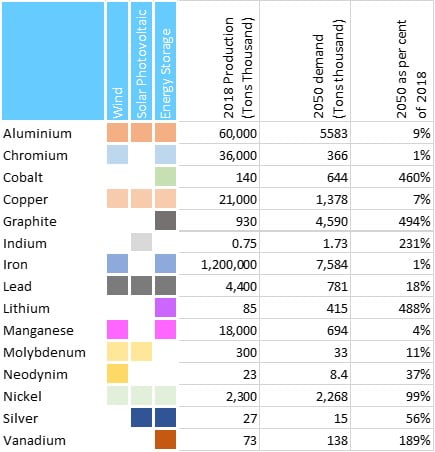

This column focuses on the critical elements for the clean energy transition. Conveniently, in 2020, the World Bank Group report Minerals for Climate Action: The Mineral Intensity of the Clean Energy Transition identified 17 minerals required across what they classed as low-carbon technologies. These minerals and the technologies they are necessary for is shown below.

The World Bank Report also included data on 2018 production and the amount of the additional output expected to be required by 2050 to meet the needs of the clean energy transition (except for Zinc for some reason).

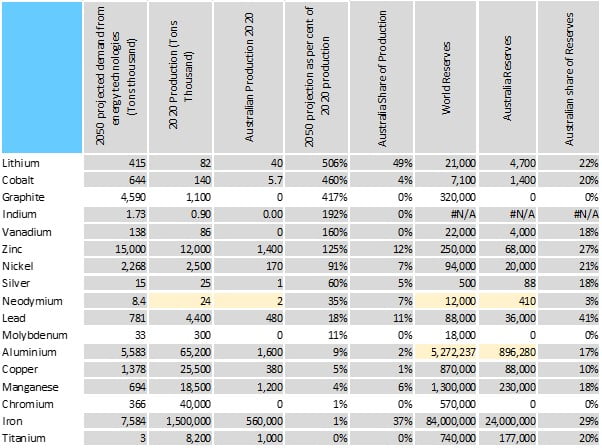

The US Geological Survey provides data on all the minerals we extract. The Mineral Commodity Summaries provide detail on global production and reserves of all minerals. The chart below shows in the first column the WorldBank 2050 projection; the remaining data comes from the USGS. The minerals are sorted in (decreasing) order of the ratio of the extra demand from clean technologies in 2050 to current (2020) world production. (Cells in yellow rely on calculations, see footnote). Reserves are known reserves; in some cases, the USGS also lists known resources. In almost all cases, there are many known resources, but the cost of extraction is often much higher than for the known reserves. Rows in white are minerals which Australia does not produce and for which we have no known reserves.

Clearly, the mineral with the greatest increase in demand in which Australia has a significant current market share and reserves is lithium. Australia’s share of Cobalt reserves is much greater than our share of current production and represents an expansion opportunity, and a similar story applies to vanadium.

Rare earths get discussed a lot because of how much production occurs in China (140,000 tonnes out of global output of 240,000, or 58 per cent). Australian reserves are relatively large and are certainly worth developing. Most of the remaining minerals are already widely used and produced in Australia, and expansion is within expected growth. In the table above, the only rare earth element is neodymium. It is used mainly in strong magnets (and hence required in the generators of wind turbines). The other rare earth elements found in the primary ores (bastnaesite, monazite, and xenotime) are cerium, lanthanum, scandium, praseodymium, samarium, europium, gadolinium, terbium, dysprosium, holmium, erbium, thulium, yttrium, ytterbium and lutetium.

The real question to be faced by a workshop on mapping the supply chains of the critical minerals is how these ores get turned into metal. Data from our old friends at the Observatory of Economic Complexity show that the major market for most of our metals and ores is China. The most notable of all is lithium, which is mainly exported as spodumene delivered to China. Recent analysis in Resources and Energy Quarterly shows a ramping up of Australian refining capabilities.

This article has focussed on the critical minerals for the clean energy transition while the Quad’s interest extends to semiconductors. The additional elements identified by Austrade that have uses, including in semi-conductors or consumer electronics, are beryllium, rhenium, scandium, tantalum, tungsten and tttrium. More broadly than the narrow Australia-US analysis, the major doping elements used for silicon semi-conductors are boron, aluminium, gallium, indium, phosphorus, arsenic, antimony, bismuth and lithium. Different doping elements are used for different bases.

The conclusion is that there is a great opportunity for Australia in critical minerals. But there is potentially a disconnect between the intent of the Quad to map the supply chains and our Prime Minister’s description of our country as being “really good at digging stuff up”.

Despite the PM’s description, there appears to be signs that the government does have its eyes beyond simple extraction to value-adding, as reported in the announcement of $2 billion in funding for the Critical Minerals Facility. The media release said: “This investment in critical minerals will make Australia a world-leader in the mining and downstream processing of in-demand resources”. Minister for Trade, Tourism and Investment Dan Teehan was quoted in the release as saying there is “an incredible opportunity for Australia to utilise its natural resources and world-leading mining know how to become a leader in the extraction, processing and supply of critical minerals”.

Strategically, what we need is the supply chain not to be dependent on China, both as a destination of our resources and a source of finished goods. Economically, we need to be adding value to the ores we extract through processing and refining. Unfortunately, the government’s record in getting money out the door on these kinds of arrangements is not good.

David Havyatt is a former adviser to federal ministers and a longtime observer of Australian innovation policy.

(Footnote: The USGS doesn’t list reserves for aluminium, listing only the reserves of bauxite. The reserves for aluminium have been calculated using an estimated recovery rate of aluminium from bauxite. The USGS also has no series on neodymium, instead listing rare earths. Despite the title, these aren’t rare. The neodymium data has been calculated by using the ratio of neodymium production in 2018 from the World Bank data and the USGS then applying that to the rare earth data from the USGS.)

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.