Way back in 2016, the SAP Institute for Digital Government (SIDG) collaborated with the Australian National University (ANU) on the topic of ‘The Digital Nudge in Social Security Administration‘.

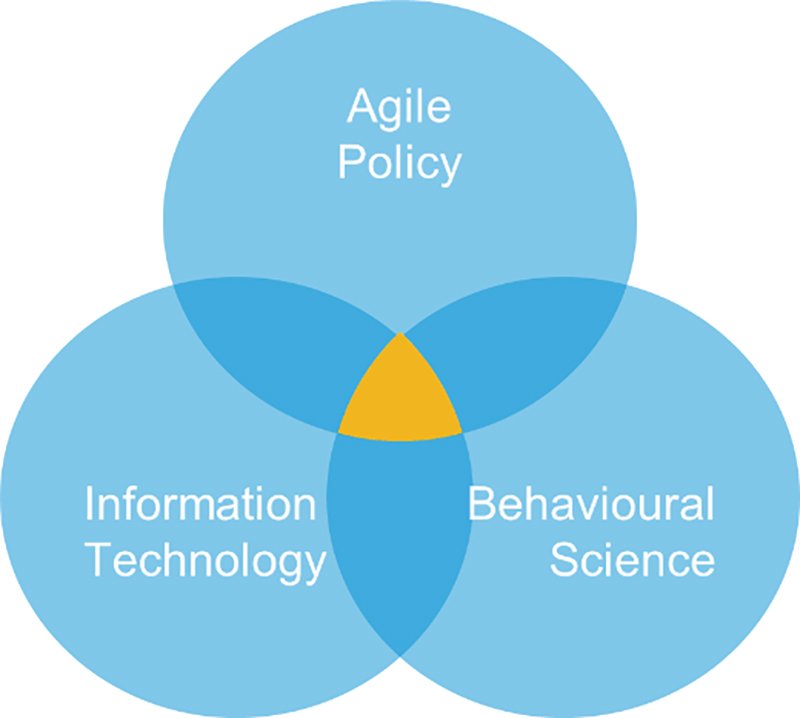

Our research looked at how digital technologies can be applied to behavioural science theory to improve social outcomes through nudging via digital channels. It’s fair to say that at the time we were ahead of the market, but times change – and certainly, times have changed markedly as a result of COVID-19!

It’s therefore worth revisiting this landmark research and considering how digital technologies might enable governments around the world to nudge citizens towards cooperation and coordinated action in containing COVID-19.

Right now, in our communities, we are witnessing the consequences of limited rationality, social preferences and lack of self-control.

In their seminal work ‘Nudge: Improving Decisions on Health, Wealth, and Happiness‘, Professors Richard Thaler (Nobel Laureate) and Cass Sunstein postulated that these human traits systematically affect individual decisions and market outcomes. It’s instructive to explore how these factors might be influencing individual decisions, for example, to stockpile toilet paper:

- Limited rationality: People focus on the narrow impact of individual decisions rather than the overall effect. For example, I’ll buy some extra toilet paper now because I’ve heard that it might be in short supply later. I make this individual decision without realising that I’m inadvertently contributing to the overall effect of supplies running short, which will ultimately impact me – along with everyone else – in the long run.

- Social preferences: People have a social preference for equitable outcomes. For example, I’ll be less accepting of my local supermarket increasing the price of toilet paper in response to a growth in demand than in response to a rise in their cost of supply. Even if the price rise is the same in both cases, my willingness to pay a premium is influenced by my perception of fairness.

- Lack of self-control: People tend to give in to short-term temptation rather than stick to a long-term plan. For example, even though I have more than enough toilet paper at home, I’ll still buy more if I find it somewhere on sale. I know that I don’t have anywhere to store additional rolls of toilet paper, but when presented with the opportunity to purchase such a sought-after item at a discounted price, I won’t be able to resist.

As has been demonstrated across the globe, government assurances, pleas, and directives have failed to prevent emotional shoppers from emptying shelves in anticipation of future shortages. Now similar assurances, pleas, and directives are being made in relation to the much more serious issues of self-isolation, social distancing, and personal hygiene.

Will citizens heed government rules and regulations now when they haven’t in the past? Certainly, the Chinese government has had great success in curbing the spread of COVID-19, but most Democratic governments don’t have the same controls available to them as in Communist China. What then is to be done?

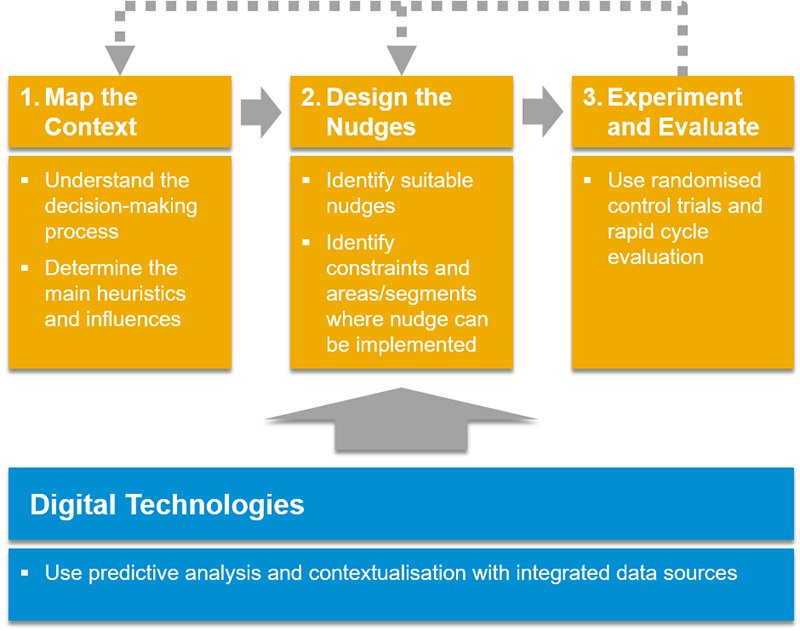

In our aforementioned research, the SIDG and the ANU described how digital nudging might be used by governments to drive behavioural change for social good.

Empirical evidence told us that certain human actions result in better social outcomes, and digital technology is enabling us to reliably predict those outcomes based on observed behaviours.

This caused us to ask: how might we leverage default human nature to positively influence social outcomes, and could we apply technology to influence individual decisions at scale?

Where Thaler and Sunstein (2008) defined a nudge as: “Any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behaviour, in a predictable way, without forbidding any options, or significantly changing their economic consequences.” We defined a digital nudge as: “Individually targeted processes, facilitated by information technology, to achieve social policy outcomes” (Gregor & Lee-Archer, 2016).

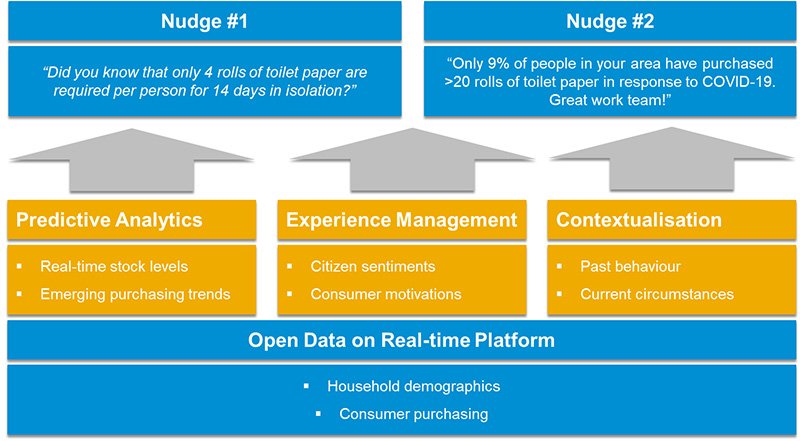

Moreover, we proposed that predictive analytics and contextualisation capabilities can improve the effectiveness of traditional nudging by enabling the shift from reactive to proactive interventions and by making nudges more targeted to individual circumstances.

- Predictive analytics is a specific field of data mining in which large stores of data are analysed to detect patterns and to predict future outcomes and trends. While predictive algorithms have been used for many years, they have typically been restricted to operating on pre-existing data. Real-time computing platforms have changed this by allowing data to be analysed as it’s created. This means that analytical discoveries can be applied to adjust government action dynamically, thereby influencing trends as they emerge.

- Contextualisation is the next evolution of personalisation: blending together information about past interactions and anticipated behaviours with present motivations and intent. Where personalisation attempts to anticipate future behaviours based on past activities, it lacks the in-the-moment context of the citizen’s current circumstance. This is important because it’s precisely that current context that’s most relevant and useful for predicting future behaviour.

Of course, our thinking has evolved since 2016, and so we would now add experience management into the mix.

- Experience management brings together operational data (O-data) about what is happening, with experience data (X-data) that tells us why it’s happening. This fusing of X+O data can enable governments to better understand citizen sentiments and motivations, and thereby take effective action. Importantly, since sentiments and motivations are constantly changing, governments need to embed feedback and analysis throughout their business processes and at every point of citizen interaction.

With this in mind, let’s return to our example of stockpiling toilet paper and see how governments might apply digital nudging to curb this behaviour…

An online Toilet Paper Calculator suggests that to last 14 days in isolation, each person requires only four rolls of toilet paper. So, the average American household (2.6 people) should be able to get by with just a single pack (10 rolls). Most likely, very few consumers did this calculation prior to purchasing, so a simple SMS informing citizens about how much toilet paper they actually need could be quite effective. It might even be possible to target the digital nudge by advising the required number of rolls for a given household.

Another approach would be to leverage the behavioural science influencer of social norms. An online poll of over 6,000 Australians indicated that only 9% had purchased more than 20 rolls of toilet paper due to COVID-19.

This sort of statistic could be promoted via digital channels, especially in geographic areas where a small percentage of people have been observed to be buying in bulk. To further improve effectiveness, the poll could be extended to understand what’s motivating consumer purchasing decisions (e.g., Why did you decide to purchase X rolls of toilet paper?).

These same capabilities could be applied by governments to nudge citizens towards cooperation with rules and regulations relating to self-isolation, social distancing, and personal hygiene. The Behavioural Insights Team’s MINDSPACE checklist provides nine of the most robust (non-coercive) influences on human behaviour, including:

- Messenger: We are heavily influenced by who communicates information. A recent Forbes article suggests that “Scientists and physicians are the most trusted authorities [on COVID-19], along with officials from the World Health Organisation and the U.S. Centre for Disease Control.”

- Norms: We are strongly influenced by what others do. Governments, researchers, public health authorities, and the general public are seeking to emulate successful responses to COVID-19 and to avoid repeating the missteps of others.

- Affect: Our emotional associations can powerfully shape our actions. The CDC has dedicated a page to managing anxiety and stress related to COVID-19.

Finally, it’s important to be mindful of the iterative nature of our digital nudge framework. Under normal circumstances, nudges are tested with focus groups in randomised controlled trials. While there’s a need to change certain behaviours relating to COVID-19 immediately, the potential for unintended consequences is heightened as a result of panic, so it’s important not to skip this important step. Rapid cycle evaluation approaches can assist in expediting the test-and-improve cycle, both prior to disseminating the initial nudge and to inform adaptation of the nudge as circumstances change.

While digital nudging is not a silver bullet for containing COVID-19, it is part of the overall toolkit available to governments today. As we’ve shown by way of examples, digital technologies can be used to both scale and personalise traditional nudges to improve outcomes for mass cohorts.

Specifically, the combination of predictive analytics, experience management, and contextualisation capabilities can enable governments to predict social outcomes, understand what’s motivating those outcomes, and take effective action to avoid today’s emerging trends from becoming tomorrow’s next crisis.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.