This week’s appointment of Wayne Swan’s former chief of staff Chris Barrett to head the Productivity Commission puts the annual Trade and Assistance Review it released this month under a more searching spotlight than usual.

Remarkably, the Commission used the review to target one of the key policies on which the Albanese government was elected. With Chalmers signalling plans for a “new focus”, it might turn out to have been one of the last chances for the “old” Productivity Commission to say (again) what it thinks.

The Commission doesn’t like (and has never liked) industrial policy – the idea of governments supporting industries in order to help them grow, and where possible to participate in global markets and value chains.

Its Trade and Assistance Review suggests it regards the government’s approach to tackling climate change and the energy transition as an industrial policy in all but name. It wants it subject to its gold standard scrutiny for any misallocation of resources.

Climate change and energy sticking points

How disappointing it must have been to have nothing as ambitious to scrutinise under the previous government. Except of course for the $7.9 billion a year diesel fuel tax rebate, primarily for mining companies, which the Commission’s review studiously omits to treat as support.

The Commission takes particular issue with the government’s intention to promote battery manufacturing in Australia, an idea with merit given Australia produces 50% of the world’s lithium, has abundant energy to process it, exports almost all of it, and captures as little as 0.53% of its final value.

The thinking is that Australian industry might for once move up the value chain and begin the task of diversifying our narrow trade and industrial structure, based as it is on the export of unprocessed raw materials.

In a world where the biggest gains from trade are in knowledge-driven goods and services, a resources dependent industrial structure lacks the economic complexity to achieve these gains, and is increasingly vulnerable to supply chain shocks.

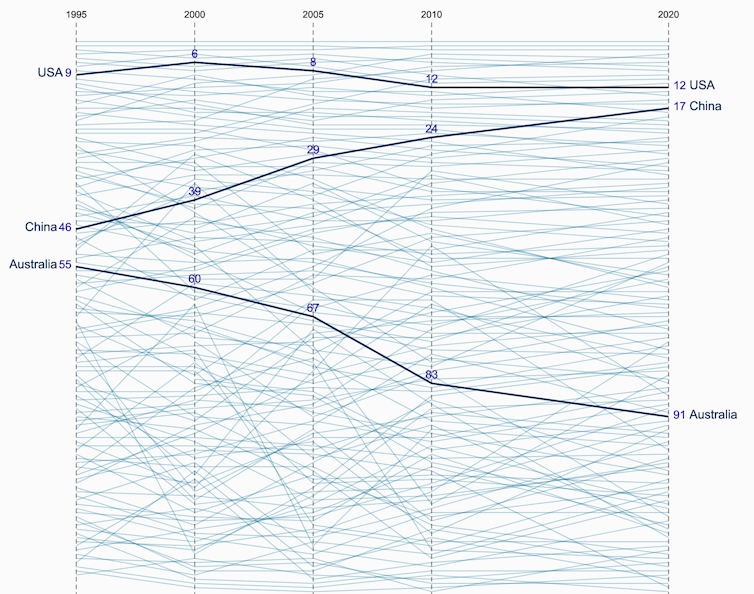

Australia has fallen to 91 out of 133 countries in the Harvard economic complexity ranking, which measures the diversity and research intensity of a nation’s export mix, just ahead of Namibia.

Australia’s economic complexity is sinking

Ranking out of 133 countries

Source: Harvard Economic Complexity Index

The problem is that while successive commodity booms made Australians richer through appreciation of the dollar, the higher dollar also made a good deal of Australian manufacturing uncompetitive, both domestically and globally.

This is what’s known as “Dutch disease”, a term coined to represent the impact of North Sea gas on Dutch manufacturing in the 1970s, and later, the impact of the UK’s discovery of North Sea oil.

Australia’s de-industrialisation is not as much a case of “market failure”, a possibility the Productivity Commission occasionally acknowledges, as one of abject policy failure.

Norway did things differently

In contrast, Norway took a public stake in its North Sea oil and gas, imposed a 76% resource rent tax and created the world’s biggest sovereign wealth fund.

Norway is now able to take part in global manufacturing supply chains in a way Australia is not, and is able to build a net zero emissions economy using world-leading research and innovation.

Such an idea is heresy in the parallel universe of the Productivity Commission, which appears to believe Australia should double down on its status as the world’s most efficient quarry and repudiate efforts to add value, as they would supposedly cost more than the benefits they produced.

The remarkable feature of this Productivity Commission approach is that it appears not to be based on evidence.

Battery manuafcture is worth investing in

In the case of batteries, experts have calculated that domestic manufacturing would boost gross domestic product by $55 billion a year, for a total investment of $35 billion through to 2035, and produce a tax take over two years of $30 billion.

Batteries are an example of how to turn a comparative advantage based on natural endowments into a “competitive advantage”, based on knowledge and ingenuity.

The fundamental problem with the Commission’s approach comes back to reliance on a “static equilibrium” model of the economy, where the assumptions themselves give rise to predictable winners and losers.

The fact productivity growth has stalled in Australia for two decades, and is now accompanied by wage stagnation, might not be due to governments ignoring the Commission’s recommendations, as some like to argue, but rather due to it implementing them.

Meanwhile, industrial policy elsewhere around the world is devised as part of a dynamic model of growth and innovation, preparing nations for the industries and technologies of the future.

As it is, the Productivity Commission is ill-equipped for the challenges Australia is about to face. Barrett’s task is a formidable one.![]()

Roy Green, Emeritus Professor & UTS innovation adviser, University of Technology Sydney This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.