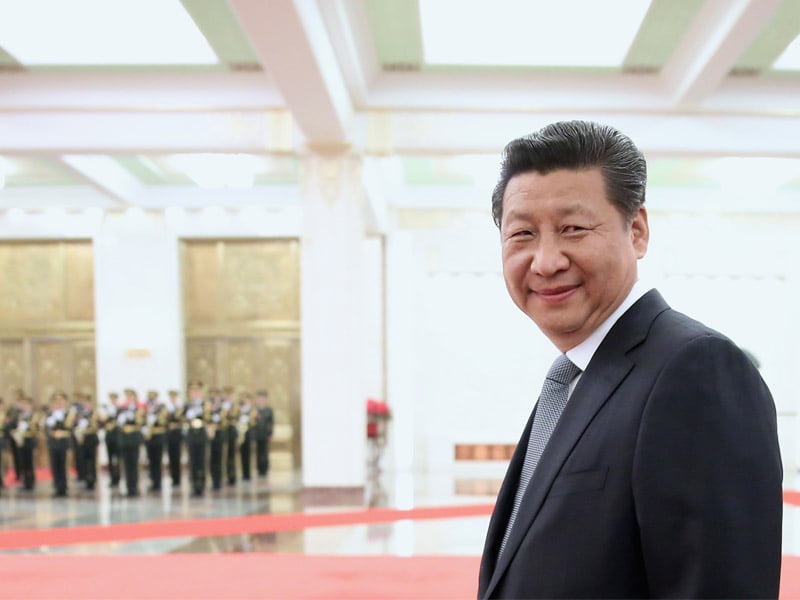

The latest phase of China’s so-called ‘going out’ program, a classic corporate-state strategy of targeting industries and specific companies, has now locked-in on innovation.

China’s top leadership are desperate to wean the economy off its reliance on infrastructure, property and manufacturing toward domestic consumption, services and technology.

Innovation has become the latest buzzword as they promote the rebalancing of the nation’s economy. But China’s climb up the innovation value chain is proving slower than its leaders anticipated.

China is pumping money into technology both domestically and internationally, with the United States as its premier destination. Chinese capital is seeking quick returns in the technology sector and many companies aim to bulk up, and in most cases transform, their businesses.

Forbes magazine recently calculated that China has invested US$2.3 billion in US technology companies since 2012.

China’s R&D spending as a percentage of GPD has blossomed from less than 1 per cent in the 1980s rising steadily to 2.5 per cent in 2013. Against a backdrop of decades’ of extraordinary economic growth, this R&D spending trajectory has been incredible.

In global R&D comparison terms, China has the most of just about everything. The number of engineers in the workforce grow by a mind-bending one million or so every year. Many Chinese universities have stepped up investment in research papers and patents, where they now lead the world.

The official line is now that China is a hotbed of innovation. But others argue that the tight restrictions on education in China, and its system of rote learning during children’s formative years has been a handicap, obstructing the ability to think laterally and innovatively.

China is keen to replicate Japan, South Korea and Taiwan’s path to technology powerhouse success.

All three countries kicked off their remarkable economic modernisations by copying Western garments and consumables. Each then finally moved into the technology sector and subsequently into domestic innovation – modelling themselves on successful US technology businesses.

Gone are the cheap knock off companies, Toyota and Kia, Sony and Samsung have become popular and trusted brands across the globe.

This end game of industrial development is referred to as technology take off and its cycle has become shorter as new countries embark on the strategy.

Two weeks ago, Trade Minister Andrew Robb inked the long-talked about Australia China Free Trade Agreement. Yet technology, which is at the very centre of just about any international business or corporate strategy or forward-thinking product remained at the periphery of the document.

This is a lost opportunity. Right now there is little Chinese money earmarked for technology and innovation coming Australia’s way.

There are serious roadblocks to attracting these dollars, many of them at the very heart of public policy. No Australian government has ever fully accepted and acted upon the ongoing technology revolution.

Successive governments have been consistently late to the party on business models, industry structures, consumer behaviours and even the operations of government.

Australia’s leadership has flip-flopped establishing divisions and departments devoted to innovation. Information Technology was added to the Department of Communications in1996. A year later the National Office of the Information Economy was created to nil effect.

Since then, policy bits and pieces have been shunted back and forth between the Communications, Industry and Finance departments like bright but difficult children, the kids that their parents don’t understand.

A great deal of significant technological innovation seeps into the secular world via the military and government laboratories. In Australia, this means organisations like the CSIRO and the Defence Science and Technology Organisation (DSTO), and even the Australian Signals Directorate (formerly DSD). Research in these groups have had their funding run down by the Abbott government.

Australia is a long way behind in the global race to overhaul their economies and government policy to cope with that change. Technology insiders will universally tell you that the top layer of public servants in Australia has a far better grasp of this than private enterprise.

This particular failure has many fathers, to invert the aphorism. The leadership of government – in terms of creating and sustaining a national technology and innovation conversation – is certainly critical, but in Australia has been patchy at best.

There was some early groping in the dark during the Howard years on internet-based innovation policy (the creation on NICTA, for example), spurred by the initial privatisation of Telstra. The technology dotcom boom was something even Canberra couldn’t ignore.

But after the dotcom bust, of course, the latest greatest mining boom began. The mining boom brought with it the notion that we didn’t, after all, have to think about the technology revolution. We could survive without it, right?

Yet the mining companies continue to succeed globally because of their continuous embrace of new, cost-saving and efficiency-driving technology. Our miners are among the most innovative in the world.

The other major piece of public policy infrastructure that needs addressing is competition policy – another political mine field that seems so far beyond the comprehension of Canberra’s current crop that it barley gets mentioned.

The benefit of highly competitive markets is innovation. This is actually more fundamental than driving down prices, as innovation is often designed to increase efficiency conditions for structural price reductions.

Until an Australian Government decides to grapple with the enormity of technological disruption and drag Australia kicking and screaming into the 21st century, China will give Australia barely a passing glance as it invests in innovation at home and abroad.

China, that authoritarian, repressive, developing world nation with an education and political system that actively discourages open debate is talking about these issues. It is spending big to try and address challenges to which Australia pays – at best – slightly puzzled lip service.

Without a conversation about these technology and innovation challenges, followed by action, Australia runs the risk – to paraphrase the late Lee Kwan Yew – of becoming the tech white trash of Asia.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.