An analysis of industry and government reports on the future of automated vehicles found they promote benefits that may exclude several socioeconomic groups and may entrench traditional gender roles, according to researchers at Monash University.

The paper found that policy and industry reports tend to assume that “automated car dependent future cities will be efficient, safe, sustainable, and equitable”, put by lead author Dr Emma Quilty. However, she says these technologically deterministic assumptions are idealistic and may exclude several socioeconomic groups.

“Policymakers or decision makers need to be more critical about pursuing this future at any cost while neglecting less utopian, but more feasible and inclusive alternatives…that’s the problem with technological determinism, it’s that technology is at the heart of it [rather than people],” Dr Quilty said.

An automated and electric future is seen as an inevitability in reports published by consultancies and the government, according to the analysis.

The paper, titled ‘Automated Decision Making in Transport Mobilities: Review of Industry Trends and Visions for the Future’, was published online on Monday by researchers at the Emerging Technologies Research Lab at Monash University and the ARC Centre of Excellence for Automated Decision-Making and Society at RMIT University.

Dr Quilty builds on the definition of technological determinism developed by Evgeny Morozov and considered its pervasiveness in her analysis. The ideology reduces complex social and political issues, such as transport, to “neatly defined problems with definite and computable solutions, or as transparent and self-evident processes that can all be easily optimised if only the right algorithms were in place”, according to Dr Quilty.

She says solutions based on technological determinism tended to be individualised, which “sidestep systemic reform and degrade our awareness of the context in which we live”.

The researchers analysed the content of 60 industry and policy reports, published between 2015-2021 to identify key trends and claims about automated decision making (ADM) in vehicles and mobility. Of the reports, 46 were written for Australia specifically, while 14 had an international focus.

Included in the analysis were 11 government reports from the Commonwealth, Victoria, NSW, South Australia, and Northern Territory. There were also three policy papers from the National Transport Commission included.

The paper identifies and encourages caution on five key claims commonly repeated about autonomous vehicles. These are improved safety, congestion mitigation, increased accessibility, environmental sustainability and resilient communities, and improved convenience. It then visualises “three speculative cases” based on the “dominant industry visions”.

The first archetype is known as Pod Man, a professional, able-bodied, and often male, passenger who rides alone in an autonomous electric vehicle unburdened by complications of gender, ethnicity, class, (dis)ability or familial responsibilities.

Building automated vehicles around the Pod Man leads to autonomous vehicle design that “turns your commute wasted time into profitable, new working time, and turning it into a second office”, Dr Quilty said.

“Designers, engineers, and town planners design transport and travel for cars around employment, whereas the kind of travel women tend to do tends to be around unpaid care responsibilities. Men will more likely take a direct commute…whereas women are more likely to do multiple short trips, and they’re also more likely to walk or take public transport to do that.”

She adds that if future cities and autonomous vehicles continue to be designed around employment the journeys taken by women are “going to be longer, it’s going to be harder, and it’s going to be less safe”.

Family Man is the second archetype visualised in the report. He sits at the front of the automated vehicle, liaising with his digital voice assistant to direct internet of things appliances in the vehicle and at home, while his wife is depicted as the primary care giver.

The report says this highlights the issues of traditional family and gender roles, data privacy risks and hyper-individualisation, in future transport automation. It notes that Family Man and his wife are physically separated as well as by the activities they are involved in as the digital assistant serves as a second ‘smart wife’. It also expresses concern that digital assistant data could be mined by insurance companies to influence people’s lives.

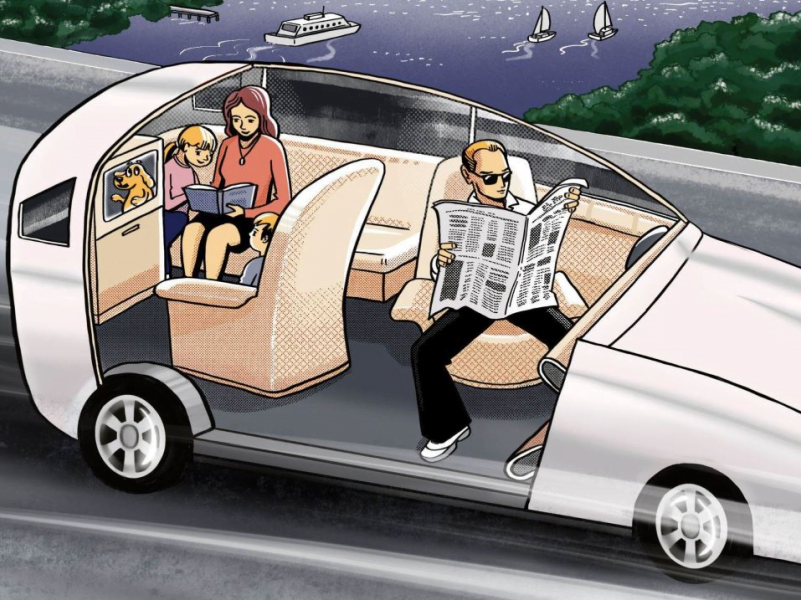

Student Man is the final archetype depicted. Young and digitally literate, with access to subsidised travel through shared mobility apps, the Student Man is considered the ideal ‘mobility as a service’ consumer. This depiction considers the student to already have high levels of digital and financial literacy prior to attending university.

Highlighting the relatively high cost of ride sharing services, such as Uber, in the image draws attention to the potential to punish people who have no choice but to use less efficient forms of transport due to access issues such as disability or geographic location.

The paper’s analysis found that industry and government papers do not include considerations on how to involve historically disadvantaged groups, particularly as early adopters of automated vehicles are expected to be an ‘urban elite’ with high levels of income, education, and mobility, according to the paper.

The overcrowded image is also meant to demonstrate the issue of overchoice, the idea that increasing the number of choices for people can make people feel anxious and less satisfied.

Given the similarities in the language used by consultants, government, peak industry bodies, there is a need for more diverse voices in the transport sector, Dr Quilty said.

“We need more women, more gender diversity, more differently abled folk in leadership positions, not just figurehead positions, but we need them to bring their perspectives and experiences into the planning, designing and decision-making processes,” Dr Quilty said.

“We need greater collaboration with them during all of this policymaking and better analysis of the kinds of different gender needs within cities because when we talk about transport, we’re also talking about city design, it’s hard to detangle those from each other.”

Above all, Dr Quilty wants to avoid “that academic trap of always being kind of the naysayers and super critical”. She believes that hope and optimism are incredibly important, and said they lie at the heart of what the ARC Centre of Excellence for Automated Decision-Making and Society does.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.