Remember the optimism around the Open Banking revolution and Australia’s new digital data economy opportunity a few years back? It was enthusiastic but fleeting, having bubbled-up somewhere after the Turnbull government’s Ideas Boom and before the Morrison government’s Robodebt bust.

It was all about leveraging the Consumer Data Right (CDR), a national government legislated policy and data standards framework for a secure online data sharing system that puts consumers’ data rights in the driving seat for trusted, competitive online commerce and services.

Australia’s multi-sector approach to CDR’s planned phased rollout and implementation was a rare world first for the country.

It was planned since 2018 under the Coalition government and enacted in 2019, first for banking and then energy (Oct 2022). Telecommunications, superannuation, and insurance were to follow before CDR-enabled digital infrastructure was to ultimately go economy wide.

For consumers that gave their consent, the CDR legislation represented a new era of choice and value for products and services built upon providers’ really knowing their needs and caring enough to compete to fulfill them in sophisticated, but not creepy ways.

“Consumers can use their data to switch service providers, take out a loan, apply for a new mortgage or use budgeting apps to help manage their finances. Using CDR saves time and effort and makes it easy to manage financial and other significant life decisions,” boasts the Treasury website.

The economic and innovation spillovers were predicted to be great. The country’s fledgling and much-hyped Fintech startup sector was set to thrive under the new secure data sharing rules; and big data holders – the banks, telcos, energy, and insurance companies – by nature resistant to any new competition, saw new pathways to partnership and profit beyond their increasingly commoditised offerings.

Back in 2018, ANZ chief executive Shayne Elliot for instance, appeared a believer in the new era of CDR-enabled competition and was ready to prime his bank into action.

He told Finance Asia at the time: “If you think the way you win is by holding on to data and building walls around it, you will ultimately lose.”

Now, nearly five years on, Mr Elliott and other banking sector CEOs are baulking at high compliance costs estimated to be $1 billion and more. And under a Labor federal government, CDR is near strangled in the cradle, risking the outright loss of a strategic technology infrastructure for the country. (More on the latter below)

Even those closest to CDR implementation and adoption in banking and energy struggle to point to any substantial change to the competitive landscape or to customer-centric services.

“It’s not officially dead and no one dares to flick the kill-switch. But (deliberate) inertia is slowly strangling it to death,” said Barry Thomas, who until last September spent five intense years working on the industry side of CDR with the Australian Banking Association (ABA), and then as General Manager of the Data Standards Body.

The CDR rollout to the telecommunications, superannuation and insurance sectors has been paused until a “reassessment” at year’s end; consumer adoption is lacklustre – primarily due to a lack of education and promotion; the once-bullish growth prospects of the Fintech startup sector is stalled as players quietly try to work out how to pivot back to the old world of screen scraping for access to customer data; and the vested interests of Australia’s big data holders, critical to successful rollout of the CDR-enabled data economy system, remain very much intact.

Mr Thomas quit due to burn out. Late last year he penned a Substack post detailing the many complex machinations holding the CDR-enabled data economy opportunity back.

He – and others – told Realpolitech it was another tragic case study in missed opportunity for the country because of how government policy is implemented.

It has been another case in a long list where lack of technological foresight, commitment, and follow-through derails highly strategic and high-economic impact technology projects in Australia.

“A really good idea takes years to get support, more years to develop and implement and then, when there are no more announceables and it becomes a bit boring, the lobbyists for the entrenched interests come out and strangle the initiative to ensure they don’t face increased competition.”

He cites technical complexity, an unclear priority focus easily manipulated by powerful vested interests in no rush for change or competitive realignment, lack of treasury and ministerial leadership and a legal minefield only armies of lawyers on the clock could love, as just some of the bottlenecks that have put the CDR on Australia’s endangered digital transformation initiative list.

An inadequate governance structure was the original sin, said Mr Thomas.

The CDR initiative has four distinct entities represented – Treasury, which is the lead agency; the ACCC, the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) and the Data Standards Chair – but no one in charge, he says.

“Despite endless requests from stakeholders, the CDR has no operating entity, just a wishful hope that enforcing rules backed by standards will be enough.”

Real authority for CDR under the Labor government resides with the Assistant Treasurer and Minister for Financial Services, Stephen Jones.

Another failing has been a lack of representation by consumer groups, which initially engaged well with the initiative, but dropped out after years of volunteer contribution at great cost of their limited time and budgets.

The CDR digital infrastructure initiative was always going to be a complex beast and a massive undertaking in design, implementation, and compliance.

But in an oligopoly-structured and competition-constrained domestic market like Australia, its goals were noble and the longer-term prize economically strategic: to promote competition and innovation; to empower consumers to use data held about them for their own benefit; and to seed and promote a robust and trustworthy data economy.

The CDR’s early advocates and designers included an economically and technologically savvy collection of people across government, technology, consumer, and data standards bodies.

They included the CSIRO’s Data61 under then chief executive Adrian Turner, former IBM Australia chief executive Andrew Stevens, who is also head of Innovation Industry and Science Australia (IISA) and is the CDR Data Standards chair, and Mr Thomas.

What these early champions of the CDR initiative saw in parallel with the rise of the global digital data economy was a world that is moving from companies operating within discrete industries – siloed and largely separate from customer needs – to one of ‘domains’.

But customers don’t live and think in terms of industries. A domain approach serves customers’ end-to-end needs in areas such as home, health and life, mobility, energy, education, secure supply chain and professional and financial services.

It’s a massive shift which is enabled by secure digital and data infrastructure.

The mismatch between a company’s industry-based mindset and a customer’s domain-based need often results in fragmented customer experience, with the company solving for only parts of the domain need and the customer having to integrate and add to the fragmented pieces.

While the domain approach is already manifest in the success and multi-sector ambitions of Big Tech platform companies from Amazon to Apple to Shopify, it requires a big mindset change for companies and government agencies.

At home in Australia, people in NSW have already experienced more than a glimpse of the power and benefit of the domain driven approach in the reform of Service NSW. That successful reform was led by then NSW Liberal Minister for Customer Service and Digital Government, Victor Dominello, and by Ian Oppermann, NSW’s chief data scientist working within the Department of Customer Service.

The success of the Service NSW rebuild prompted Bill Shorten, the federal Minister for Government Services, to tap Mr Dominello to chair the current advisory group for a top level overhaul of the tortured Services Australia and MyGov digital service platform. The appointment was widely applauded.

Mr Dominello exhibits the kind of leadership for collaborative problem-solving enabled by real-time and secure data. He is genuinely passionate that the digital and data age must be better leveraged for citizens and consumers and to restore trust in government’s delivery of services.

“It’s structural change – in business, industry and government – that’s needed to solve a litany of modern-era problems,” Mr Dominello said. “The tools to do it are either already there, or fast coming on-stream. It’s critical that we have the foresight, the pragmatism and the technical expertise to properly assess and implement them.”

For businesses, the prize of reorienting toward domain services is well worth the effort and costs, especially with AI-enabled Big Tech giants hungry to swipe share of the legacy companies’ customers and markets in key industries.

A recent MIT survey identified domain-oriented firms were top performers with a huge premium on revenue growth and net profit margin.

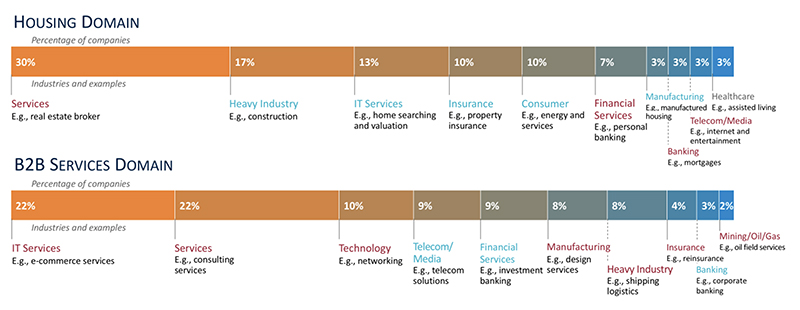

Industry Composition of Two Domains

This trend globally is picking up steam – and with AI – it will only accelerate.

But with the future rollout of CDR-enabled infrastructure implementation stalled, and consumer adoption tepid, Australia risks falling further behind.

Despite all this, Mr Thomas is still passionate about CDR’s growth and innovation-enabling potential.

“The Consumer Data Right is a wonderful and rare example of Australia leading the way with something genuinely cool and transformative. Adding in some Artificial Intelligence will take the potential opportunities, and the risks, to the next level,” he says.

“In the not-at-all-distant future, one might simply say, “Hey (AI), find me a better home loan,” and the AI will be able to make all the necessary API calls and perform the data analysis to fulfill your request on the fly.

“For this to work, Treasury will need to get its act together to make some rule changes, but at a technical level, this is probably doable now. No banks, no data intermediaries, no mortgage brokers, no personal data leaking into poorly managed databases…just you, your AI, and the right home loan for your needs.”

It’s a nice dream. But for now, the Labor government only has eyes for the Green Energy Superpower ambition.

Last week’s Realpolitech column highlighting the challenges other more industrially advanced economies are having with the net zero mandates and renewable energy insecurity, earned plentiful feedback.

Much of it went like this: “Yes, we know there are huge challenges to pulling this off, but it’s all we’ve got, (to rally and reinvigorate industry) so let’s forge ahead.”

Realpolitech baulks at that reductive mindset. It’s not all we’ve got. If only we could learn to walk and chew gum at the same time, we might be able to pursue several innovation-driven missions in parallel, because they all feed and fuel on one another.

Enabling a secure and robust digital economy should be a priority in the mix.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.