Australian researchers have developed software that can reliably detect a premature baby’s face in an incubator and remotely monitor vital signs without the need to attach adhesive sensors on their fragile skin.

The software designed by University of South Australia researchers, published in the Journal of Imaging, involves a computer vision system that can automatically detect a tiny baby’s face in a hospital bed and remotely monitor its heart and breathing rates from a digital camera with the same accuracy as an electrocardiogram (ECG) machine.

Vital sign readings matched those of an ECG and, in some cases, appeared to even outperform the conventional electrodes, the university said.

The advancement is a first step in using non-contact monitoring in neonatal wards, avoiding skin tearing and potential infections from adhesive pads.

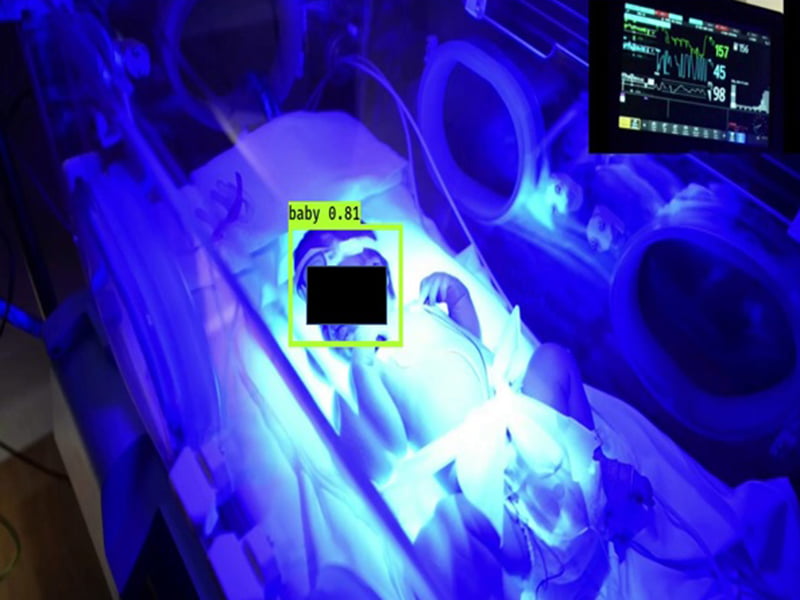

Using artificial intelligence-based software to detect human faces is now common with adults, but the University of South Australia said this is the first time that researchers have developed software to reliably detect a premature baby’s face and skin when covered in tubes, clothing, and undergoing phototherapy – whereby a bright light is shone on them, making it challenging for computer vision systems.

As part of the research, seven infants in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) at Flinders Medical Centre in Adelaide had their heart and respiratory rates remotely monitored using a digital camera while engineering researchers and a neonatal critical care specialist from the University of South Australia monitored the results.

Infants were filmed with high-resolution cameras at close range and vital physiological data extracted using advanced signal processing techniques that can detect subtle colour changes from heartbeats and body movements not visible to the human eye.

“Babies in neonatal intensive care can be extra difficult for computers to recognise because their faces and bodies are obscured by tubes and other medical equipment,” Professor Javaan Chahl, one of the lead University of South Australia researchers, said.

“Many premature babies are being treated with phototherapy for jaundice, so they are under bright blue lights, which also makes it challenging for computer vision systems.”

The “baby detector” component of the system was developed using a dataset of videos of babies in NICU to reliably detect their skin tone and faces.

Neonatal critical care specialist Kim Gibson said using neural networks to detect the faces of babies is a significant breakthrough for non-contact monitoring.

“In the NICU setting, it is very challenging to record clear videos of premature babies. There are many obstructions, and the lighting can also vary, so getting accurate results can be difficult. However, the detection model has performed beyond our expectations,” Ms Gibson said.

“Worldwide, more than 10 per cent of babies are born prematurely and due to their vulnerability, their vital signs need to be monitored continuously. Traditionally, this has been done with adhesive electrodes placed on the skin that can be problematic, and we believe non-contact monitoring is the way forward.”

Professor Chahl said the results are particularly relevant given the COVID-19 pandemic and need for physical distancing.

The study is part of an ongoing project to replace contact-based electrical sensors with non-contact video cameras.

It follows the University of South Australia team developing technology in 2020 that measures adults’ vital signs to screen for symptoms of COVID-19, which is now used in commercial products sold by North American company Draganfly.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.