Australia’s digitally branded budget is being breathlessly marketed to drive Australia towards becoming a leading digital economy by 2030. Except that the plan is twenty years too late, and the ground underneath it is already cracking.

Australia had a reasonable digital start in the early 2000s. But Australia squandered the early advances made and slid into a complacency that 20 years later, has the nation at a significant capability deficit.

And worse, this national capability deficit will take decades to remediate. And that was the situation before COVID.

In comparison, the strategy of ‘informatization’ that was being embarked upon by China in the early 2000s was gargantuan. ‘Informatization’: the transformation of the entire Chinese economy and society through the deployment of information and communication technologies in business, social, community, government and military functions.

Hundreds of thousands of public officials in the national government were required to undertake, and pass, multi-year “informatization” programs. These were not some light-touch executive familiarisation awareness raising sessions. China delegates at APEC, UN and other international forums spoke in detail about the extensive national efforts that were underway.

This in large part explains China’s emergence as an AI superpower.

Australia’s ambition to be a leading 2030 digital economy requires more than a pick list of ‘digital’ and systems projects – many of which are re-do’s from previous attempts.

But it is the underpinning capability and culture of the Commonwealth administration that will be the critical success factor into the future: not the expenditure on consultants.

Across many years, the APS State of the Service Reports have painted a picture of the APS as increasingly homogeneous: older, less diverse, less mobility and fewer people with disability.

Digging deeper, not only is the APS getting older (as would be expected), but between 2018 and 2019 the numbers in the younger demographics (20-29 years) fell. This paints an extremely worrying trend: this younger cohort are the stewards in the decades ahead.

Of great concern, in the 2019 State of the Service Report more than 70 per cent of respondents identified capability gaps in the areas of data, leadership and technology. And 73 per cent identified agency barriers in the use of data.

Astonishingly, only 1 per cent respondents self-identify as working in “digital” roles. In an era when everything is digital and digital impacts all policy domains, a paradigm of what is and is not digital shows the enormity of the challenge confronting Australia.

I wonder how many people in Apple would identify as ‘digital’. Mindset matters.

Given this capability deficit, one wonders how the APS as an institution actually formulated the digital budget and comprehended the inescapable risks.

However, it would appear that risks may not have even been identified given the silence on the “urgent” ICT capability audit, which was to be undertaken before further reform is undertaken.

But instead we have a digital budget, with hundreds of millions of dollars or more, in revisited and failed programs.

The more than $400 million to transfer existing business registers to a modernised platform to allow the creation of a single, accessible and trusted source of business data – is really the re-prosecution or at least the remediation of the year 2000 ABN/ABR program and the implementation of the unique identifier for business.

The 2014 ANAO Report into the Administration of the ABR paints a picture across government of agencies implementing their own business numbers. I have seen this first-hand with agencies devising various “provider numbers”, with program managers, system designers and architects not understanding the role of the ABR and the ABN.

I ask, what will be different this time?

Similarly, the ‘Apprenticeships Data Management System’ gets another go with more than $90 million. This is after the previous $24 million project was dumped in 2018, with the departmental secretary saying that NEC had “initially underestimated the complexity” of the system. Governance and project management weaknesses were identified.

The significant capability deficit across the APS necessary for strong governance and the management of large vendors and systems integrators, and particularly with intelligence and identity systems, is already problematic.

Over at the Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission (ACIC), an audit of the national biometrics database project found that project administration was deficient in “almost every single respect” causing the estimated cost to blow out to $94 million. This project also involving NEC was terminated by ACIC with NEC subsequently suing.

And in this same digital budget that pushes ahead with an additional $90 million for the high risk and contentious digital identity program, Facebook-like MyGov redo, and transformation initiatives – the DTA loses more than 30 staff.

In any capability audit, this would have been identified as an extreme risk.

Of course, there is no explanation as to why the ANAO has received less funding for audits at the very time when APS data and digital capability is extraordinarily deficient and cyber risks so extreme.

So significant is the lack of appreciation of the depth of governance required to deliver outcomes over the longer term, that the DTA see the ASL cap as a factor to be managed with its contingent workforce. And of course, a workforce augmented by major consulting firms.

Capability development requires far more than workforce augmentation. The Chinese figured this out more than twenty years ago when launching the forward looking “informatization” program. Deep capability in people is necessary in order to drive transformation.

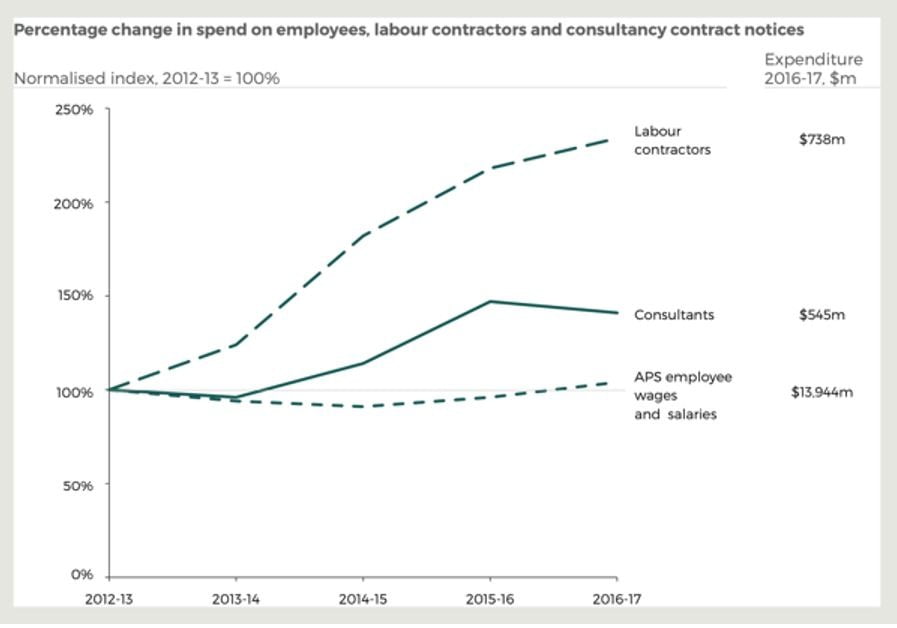

This was one of the most interesting reveals of the Thodey Report: the mapping of the trend of expenditure on APS employees and consultancies (page 186).

And during this same period, there have been multiple and major program failures.

The Thodey Report’s unequivocal call to action was:

“…the APS needs a service-wide transformation. It needs short term change and long term reform…”

COVID has now accelerated the urgency and exacerbated the risks.

We need to build deep Australian sovereign and public sector capability. We need to go beyond “training programs”, to a mobilisation footing – with the APS massively scaling its graduate and traineeship intake 10X in collaboration with Australian universities.

To generate a massive injection of capability in the APS, not consultants, to give the transformation momentum and stewardship.

But instead, what we really have is a digital repair budget that revisits, remediates and re-does programs from the past 20 years. This is a recipe for a fractured digital future.

In my opinion, half of this is not only not necessary, but not achievable due to the risks that are ignored and the under-investment in people which will take a decade to correct.

If we don’t change the parameters, why should we expect a different result?

Marie Johnson was the Chief Technology Architect of the Health and Human Services Access Card program; formerly Microsoft World Wide Executive Director Public Services and eGovernment; and former Head of the NDIS Technology Authority. Marie is an inaugural member of the ANU Cyber Institute Advisory Board.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.