As a former Director of R&D for major multinationals in Australia and in Holland, and founder of a successful technology startup in Australia, I can claim a unique perspective on the effectiveness of the R&D Tax Incentive, and how it can be substantially improved to benefit the R&D ecosystem in Australia.

The Dutch WBSO and the Australian R&D Tax Incentive are both designed to encourage R&D activities, but the WBSO appears to have been more effective in stimulating an enviable innovation ecosystem in the Netherlands.

WBSO granted €1.2 billion (A$2.16b) in tax credits to companies in 2019, while the Australian R&D Tax Incentive granted A$2.8 billion in tax offsets in the same year. Yet Holland is ranked 5th in world rankings for innovation ecosystem, whereas Australia is 23rd.

It is not the amount of money that is the problem. There are key differences in how the R&D tax is administered that appears to be more effective in the Netherlands than in Australia.

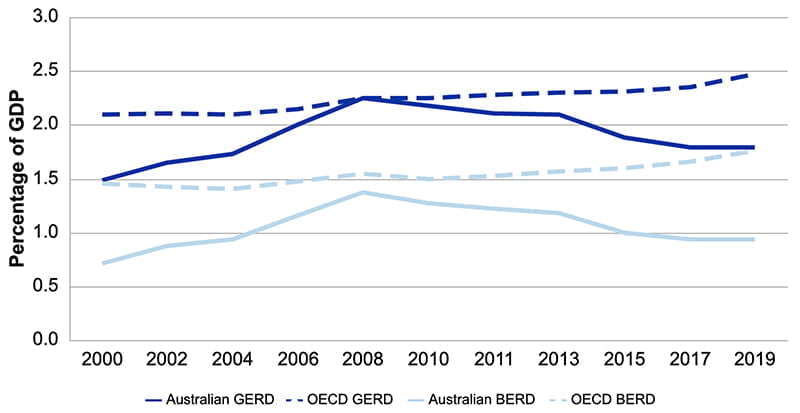

What is particularly concerning from an innovation perspective is that large companies appear to be exiting from the research ecosystem in Australia and locating their R&D centres in places like the US, Netherlands and Singapore.

According to a recent report by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO), the number of large companies claiming the R&D tax incentive has declined by 14 per cent since 2013-14. In addition, the report found that large companies are claiming a smaller proportion of the total R&D tax incentive benefits each year.

Interestingly, it may not be because Australian incentives are not generous enough. In many measures they are comparable. But the way the incentives are administered is not effective in encouraging additional R&D.

In the Netherlands, the WBSO provides a tax credit to companies who enter the scheme, which can be directly credited into their P&L account. This allows companies to spend the credit on further R&D activities. (They are actually encouraged to do this).

In contrast, the Australian R&D Tax Incentive provides a tax offset, which can only be claimed after the company’s tax return has been audited. This does not provide the same direct and immediate incentive for companies to increase their R&D expenditure as it cannot be integrated into the budgeting process for R&D spend. In large companies balance sheet (treasury) is managed separately to P&L (operating business).

My lived experience reinforces this. As R&D director of Mars in the Netherlands the email from the tax office confirming the tax rebate arrived in the middle of the financial year, unpredictable both in timing and amount – impossible to budget for in other words. And it was in the form of a cheque that got paid into the Profit and Loss (P&L) account. This created a budgetary problem to be solved, because if it wasn’t spent then it would be result in unplanned windfall profit and extra tax paid.

In addition, the WBSO required that the money should be spent on R&D. Of course what happened was that the ecosystem in Holland responded with universities and technical consultants working to create programmes that could use the money.

This created positive feedback to the innovation ecosystem, providing funds year after year that went to the universities, and technology and innovation agencies, building national capability and making the Netherlands one of the most innovative and prosperous economies in Europe.

In Australia, when I became R&D Director for Masterfoods, the business received more R&D incentive dollars than in Holland, on paper. But in practise the treasury function received a notice from the ATO that the tax bill would be a few million dollars lower as a result of the R&D efforts of the company.

Treasury was a part of the finance function reporting into regional treasury, and they would thank R&D for the tax reduction. But there was no mechanism for taking that money and putting it back into R&D. So R&D was pared down to the minimum to keep the business going with H1 innovation, and risky, more innovative work was not pursued in Australia.

If the same money had come in the form of a cash rebate, with some strings attached to spend it on R&D, then most of the money would have gone to CSIRO, universities and more speculative internal projects. It would have fuelled the ecosystem.

When I became R&D Director at Pepsico, the situation was identical, but this time the treasury function was in Hong Kong and it consolidated tax for the whole region. Austalia’s $3m RD tax contribution was too small to even feature in the tax report back to New York. And yet it would have been more than 10 times my Research budget as R&D director.

Recently I founded a plant-based meat startup, v2food that benefited from the R&D tax system. As long as v2food fails to deliver a profit, the R+D tax system is hugely beneficial and v2 has pushed hard to develop technology and research. But Australia’s problem isn’t startups, it’s the larger, profitable scaleable companies who are doing their research elsewhere.

I have consulted widely among multinationals and they echo my experience. Most have already downsized their R&D centres or relocated to Europe, US or Singapore. Universities do not have money from corporations directly, perhaps through CRC grants which have their own problems with respect to driving true impact.

A change in the way the tax incentive is awarded, without increasing the total would have a fundamental positive effect on large business R&D in Australia and that is important to the ecosystem.

Startups are important and well served by the current system because they are small and unprofitable. But it is large companies that have the resources to do major projects and take them global. And they recruit graduates and partner with SMEs and startups.

Innovation ecosystems without large companies participating are unhealthy. The R&D tax change should incentivise them to do significant R&D in Australia.

Nick Hazell has worked in Netherlands and Australia as R&D director at Mars and Pepsico. He has taught innovation at the University of Technology, Sydney and founded Australia’s leading plant-based meat company, v2food. He is now engaged in an algae biotech startup algenie.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.