Opinion: The announcement of the AUKUS security partnership by leaders of the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia has triggered a flood of op-eds about the implications of the Morrison Government’s decision to reboot its submarine acquisition program for a third time using US nuclear-powered technology.

However, as a tech geek it was the passing reference to trilateral co-operation on cyber capabilities and emerging technologies in the announcement that piqued my interest.

Australia, the US, and the UK already work closely together on operational cyber security matters within the Five Eyes intelligence network. This co-operation and information sharing is overwhelmingly in our national interest and anything we can do to deepen it is warmly welcomed.

The implications of the co-operation on emerging technologies flagged in the announcement are less clear. So far, details are scant.

It’s easy to use references to emerging technologies like artificial intelligence and quantum computing as buzzwords, adding a “visionary” or “thought-leading” flavour to an announcement. It’s harder to deliver substantive action.

Behind the government marketing hype, Australia’s once pioneering quantum computing industry is drifting and we are falling behind.

When Professor Michelle Simmons visited Parliament House in 2018 to spruik her work in quantum computing as the Australian of the Year, we were ranked sixth among the nine largest economies actively investing in quantum technology.

Today, we’re last.

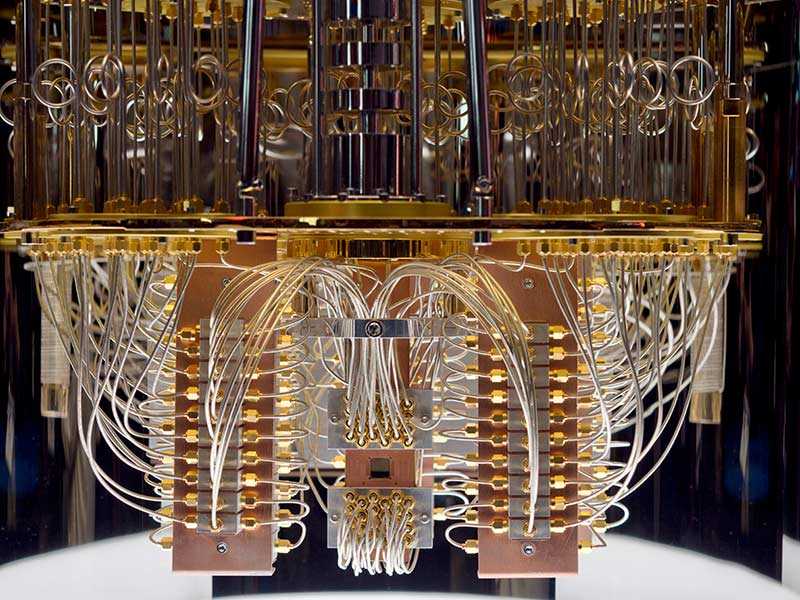

Quantum computing is undoubtedly a tantalising technology. While it’s infamously difficult to describe how it works, as an enabling technology a thriving quantum computing industry could be a productivity boon across the Australian economy.

Australian industries as diverse as battery manufacturing, urban management, green steel production, and biomedical science could all become more productive with help from quantum computing.

A recent CSIRO report conservatively estimated quantum computing could create 16,000 new jobs and be worth $4 billion dollars to the Australian economy by 2040, comparable to current estimates of Australia’s wool and wheat industries.

Despite the hopes of public relations managers around the world however, technology industries are not built on buzzwords in media statements and press conferences alone.

In the wake of COVID-19 we’ve seen a slew of governments make multibillion-dollar investments in their domestic quantum computing sectors as part of their economic reconstruction plans; Germany announced a $3.2 billion investment in quantum computing, France a $2.9 billion investment, and China plans to spend $14 billion.

Just this year, both the Australian Strategic Policy Institute and the Australian Information Industry Association released major reports outlining the opportunity and warning that government inaction risks letting it slip through our fingers once again.

According to ASPI, investment in the sector by China, the US, France, Germany, the EU, India, and Russia now exceed Australian investment in quantum by factors of up to 100:1.

When quantum computing researchers meet with Australian politicians today, they tell the story of a national brain drain as Australian quantum talent decamps to more accommodating nations. To countries with governments that have a vision for their quantum computing industries and an investment plan to match it.

Quantum computing risks becoming the latest in a long line of stories where Australian smarts make early breakthroughs in an emerging technology, only to see the commercial returns and the associated jobs realised overseas.

Australia lacks even a national strategy for developing its domestic quantum industry, let alone an investment roadmap to match that of other countries competing for our talent.

The US and the UK are not so complacent. Both nations have significant quantum computing strategies and investment commitments.

The United States will invest around $US 1 billion in quantum computing in 2021. In the UK, investment in the National Quantum Technologies Programme surpassed £1 billion ($A1.8b) in 2019.

Leaders in the UK have already begun to discuss how AUKUS nations could share emerging technology platforms, rather than incurring the costs of duplication. This has potentially significant implications in quantum computing.

But we need a national strategy to guide decisions about which platforms we are happy to use in the US and UK, and which platforms we need to invest in to host ourselves so that we can realise broader benefits for the development of our domestic quantum computing industry.

We won’t find the answers to these questions in consultations with the UK and the US. We need to determine them ourselves based on our own ambitions. If we want to realise the benefits of emerging technologies like quantum computing, we can’t just talk about them with our international partners, we need the government to act.

Sharing in the benefits of these investments as users of this technology is all well and good. But surely we can aspire to more for ourselves.

We must ask ourselves whether, in this rapidly evolving geostrategic environment, we are content to be technology takers, with our fate determined by the investment and design decisions of governments and companies beyond our shores.

Or, whether we should aspire to become technology makers, shaping our own future.

If we aspire for more, we need to ask more of our government.

Tim Watts is the shadow assistant minister for communications and cyber security and federal member for Gellibrand.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.