The food and agribusiness sector plays an important role in feeding Australians and is a fundamental pillar underpinning Australia’s economy. The sector, however, is not meeting its full potential.

This is a result of poor coordination, lack of human and business capability, a historic culture of competition, and an anachronistic view of the dynamics and interconnectedness between the two critical components of the sector – agriculture and food and beverage.

Various studies and estimates – including Food Innovation Australia Limited (FIAL)’s Capturing the Prize – demonstrate that Australia’s Food and Agribusiness sector is not meeting its potential.

Capturing the Prize estimates that the sector could be three times the size by 2030 (that is, $200 billion on a value-add basis) and create an additional 300,000 jobs, if the sector was: better coordinated and collaborative in nature; and where public investment recognised the unique traits of the sector, rather than treating it the same as other priority sectors in the economy.

Opportunities and challenges

The Australian food and agribusiness sector has been under siege on many fronts – with production challenges arising from a rolling catalogue of natural disasters (prolonged drought, Black Summer bushfires and floods), a persistent mice plague in the southeastern states, and the supply chain blockages created by domestic and international border closures during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Rising geopolitical trade tensions in China, and now Ukraine, including ongoing domestic and global travel restrictions, have compounded the challenges facing food supply chains.

Despite these many challenges, the sector has maintained its contribution to the Australian economy – both in terms of gross value added and employment – and, most importantly, feeding Australians.

A perfect storm for change

An important trend has emerged through these disruptions. Consumers worldwide are increasingly focusing on food safety, food security and the origin of the food in their purchase decision.

Understanding the food supply has become front of mind. Never has food, and all it entails, from paddock to plate, had a higher public profile. For Australian agrifood industries, this trend presents a significant opportunity to leverage and build on our already strong, globally renowned reputation as a producer of clean, green food.

Reframing public understanding of food and agribusiness

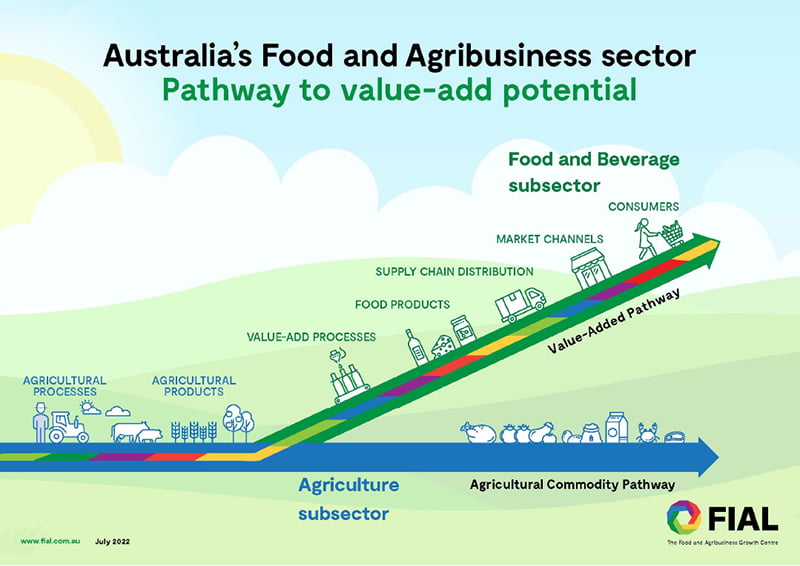

The food and agribusiness sector is made up of two components or sub-sectors – agriculture (pre-farm gate), and food and beverage (or food manufacturing post-farm gate). The agriculture subsector produces the inputs or ingredients for food and beverage manufacture.

To labour the point, the agriculture sub-sector produces raw products (milk, grain, animal carcass) which require varying levels of processing, manufacture or value add, within the food and beverage subsector, to become the food we all recognise and purchase from the supermarket.

Together, the agriculture and food and beverage subsectors form one value chain, one sector, or one ecosystem.

Despite this, the interconnectedness of the two sub-sectors has been overlooked for decades by many policymakers, industry leaders and investors. While both subsectors can exist separately, and largely have, neither will meet their potential by doing so.

Of critical importance now to the industry and national debate: Australia’s competitive advantage and sovereign capability, specifically as they relate to the regions, job creation, and national wealth creation, will not be met unless these two sub-sectors are brought together in one coordinated national policy framework, with targeted investment strategy along the value chain and food ecosystem.

It is for this reason that we commend the government’s decision to bring both ‘sub-sectors’ into the one portfolio, and early reports of developing a national food strategy.

A value chain waiting to be tapped

Today, the Australian food and agribusiness sector plays contributes $69.7 billion to the economy on a value-add basis. The agriculture subsector contributes $40.3 billion value add; and the food and beverage subsector contributes $29.4 billion value add.

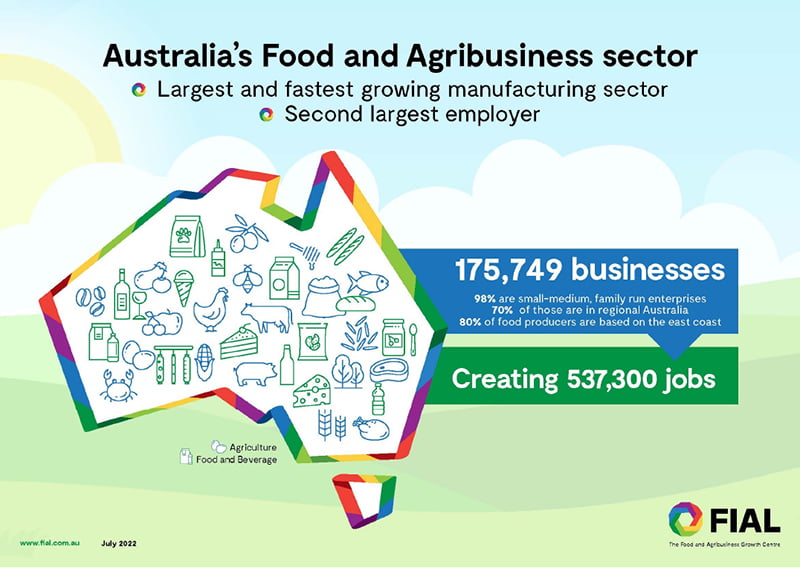

It employs 537,300 people directly, and is powered by 175,749 businesses,1 98 per cent being SMEs and 70 per cent located in regional Australia (Figure 1).

Historically, these sub-sectors have been dealt with separately by policy makers (Figure 2). This is particularly evident in the $500 million investment (from farmer levies and Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry) in the well-defined agriculture innovation ecosystem delivered through the 15 rural research and development corporations (RDCs).

In contrast, the food and beverage (or food manufacturing) subsector receives a fraction of this industry infrastructure and investment. This has resulted in missed opportunities to leverage each sub-sector’s success for innovation and building capacity and capability, including trade and market access.

The inherent dependencies and interconnecting relationships of participants in the value and supply chains, including the supporting regulatory frameworks that underpin this food system, provide the opportunity to correct this imbalance in investment.

This would enable the sector to not only meet its domestic potential but be a significant player on the global food stage meeting the growing demand for what Australia produces and manufactures.

The need for one organisation with a national perspective that oversees the food system (agriculture and food manufacturing) in Australia has never been more important than it is today.

The way forward

1. Investment focus on capability build, not just infrastructure build

Gap – 98 per cent of businesses within the sector are small and medium enterprises (SMEs), most not having the internal capability to compete or participate in many of the past or current programs (like the Modern Manufacturing Strategy or the National Reconstruction Fund) designed to grow businesses across the economy.

Further, many of these programs provide only for hard infrastructure, when soft infrastructure is just as critical to success. Lower levels of investment in research and development (R&D) among SMEs, together with the need to build capacity and capability for scale, hampers their ability to compete globally at their full potential.

Solution – Businesses within the sector range in their capacity and capability to ‘compete’. Working across the value chain, FIAL has mapped this variation of business needs on the basis of Business as Usual; Business Readiness; Innovation Readiness, and Market Readiness.

Government and industry programs, policies, and investment need to reflect the variation in size, need, and capability, rather than adopt a ‘one size fits all’ approach.

2. Criticality of collaboration

Gap – Recently, there has been a renewed focus and public investment in different programs focused on improved collaboration to support businesses in the sector. Whether these programs are called precincts, hubs, or clusters, invariably they acknowledge the need for SMEs to collaborate and coordinate efforts to achieve economies of scale to innovate and drive profitability and growth. Countless programs exist at both national and state level, across nearly every portfolio, providing uncoordinated programs, resulting in a duplication of resources and lack of impact.

Solution – A nationally coordinated, agency agnostic approach should be adopted to support SMEs across all sectors build capability, scale and unlock their potential. Pooling resources or at least targeting efforts to build the capacity and business argument for collaboration could have a transformational impact on our national business and innovation landscape.

In a small way, FIAL has been piloting such an approach by chairing the national organisation (TCI Oceania) to build the capacity and ecosystem for collaboration across multiple sectors, including food and agribusiness.

3. Whole-of-sector leadership

Gap – The food and beverage sub-sector has an uncoordinated and inadequate ecosystem, receiving a fraction of public and private support for innovation, industry infrastructure and coordination, compared to the agriculture sub-sector. This not only impedes the potential of the food and beverage sub-sector, but also for the value-add potential of agriculture.

Solution – A serious barrier to scale is the absence of sector-wide coordination in a number of critical areas, including policy, investment in soft and hard infrastructure, R&D and innovation, and human and business capacity and capability building.

Taking a whole of value chain approach, a whole-of sector leadership would work across all jurisdictions, work with businesses regardless of size or type, and better enable the sector to meet its $200 billion potential by 2030.

The confluence of the MMS and FIAL’s Capturing the Prize – indicating the potential of a $200billion sector by 2030 – provides fertile ground for sector growth. With demand for what we grow, produce and manufacture increasing, the sector’s future is positive.

However, to meet this potential, we need the right policy measures.

Dr Mirjana Prica is the Managing Director of Food Innovation Australia Limited (FIAL), one of six Industry Growth Centres established by the Australian Government to drive innovation and business growth for the 180,000 firms operating in the food and agribusiness sector. Dr Prica sits on boards and advisory groups for clusters, cooperative research centres, universities, research and industry organisations and businesses in Australia and overseas, where she leverages her 30 years of research and commercial experience in food, agribusiness, advanced materials and minerals.

Footnotes

- Agriculture is composed of 160,465 businesses who employ 282,350 people directly. Food & Beverage (or food manufacturing) is composed of 15,284 businesses that employ 254,950 people directly.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.