There are hidden wisdoms in the old-fashioned Separation of Powers Doctrine (‘SOP Doctrine’) that could help us cleanse modern politics of its low-level corruption. The wisdom of the SOP Doctrine is that it tempers the problems of democracy with a very clever splash of meritocracy.

We need it. There is disturbing evidence of the use of public funds for the wrong purposes. The Grattan Institute has documented political patronage in the use of grants. The sleaze of grant making is an open secret.

Moreover, there is evidence of political appointments for easy jobs located in attractive foreign climes. Recent evidence from the appointment process of NSW trade positions is salient.

Finally, there is real concern that complex capital projects are now driven by political preferences rather than expertise. In Victoria, at the last election, the direction of the underground rail depended on who won the election rather than rational expert judgement.

The SOP Doctrine separates arms of government into areas which provides checks and balances, suits their skills and diminishes the stress of conflicting roles and uncertainty.

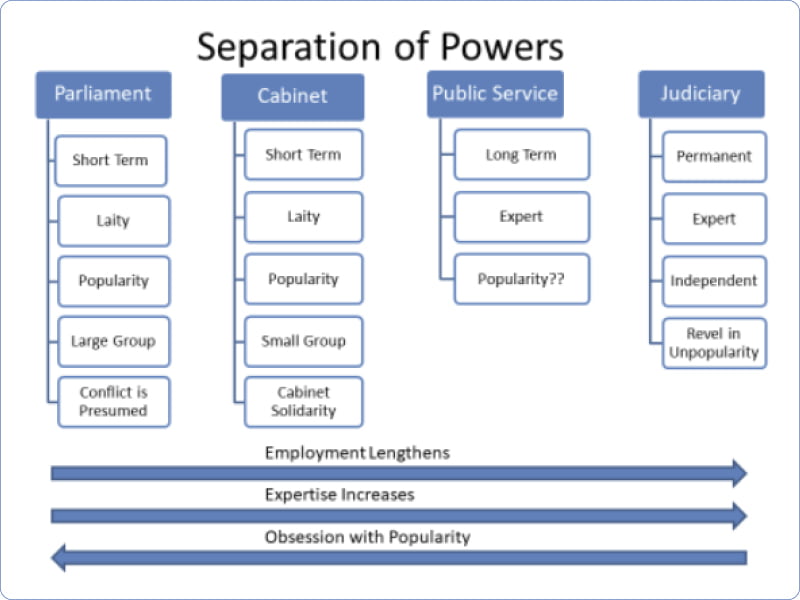

The three arms of government, the legislature, the executive (in turn divided into two as Cabinet and the Public Service) and the Judiciary are divided.

In a pure system, the three arms are prevented from trampling on each other’s patches. The balance between democracy and meritocracy happens thus.

The democratic values are represented in parliament and Cabinet. These are populated by people from the laity.

Generally, these appointments of the laity are short term so that they are particularly governed by the popular will. Repugnant decisions by short term lay representatives can be quickly solved at the ballot box.

The meritocratic values are represented in the Judiciary and public service. These are populated by trained experts.

Generally, these appointments are longer term so that decisions are made by experts who are in turn protected from retribution for unpopular but defensible decisions. Judges have permanent employment so they can resist the public will if meritocratic factors suggest.

The classic example is the lynch mob. If parliamentarians determined judicial outcomes, justice would be corrupted by prejudice and bile.

We don’t like to admit that we need to constrain democracy, but it is embedded in our systems. And for the better. Our suggestion is that there needs to be more fetters on democratically elected bodies.

Here is a depiction of the SOP Doctrine in its purest form. It balances four questions,

- laity versus expertise

- appointment by election or selection

- appointment length – the longer the appointment, the more resistant to popularity pressures

- Group size – the larger groups like a parliament give wider representation of views and consequently have more differences of views leading ferocious conflicts. Smaller groups like Cabinet suppress conflict of views in the cause of efficiency and confidentiality

If you accept that this scheme has power and integrity, then now is the time to apply this wisdom more widely. We have problems with three things: grants, politically compromised senior appointments and infrastructure decisions.

Let’s extend the SOP Doctrine more formally to these types of decisions. It is suggested then by legislative fiat; the following decisions must be removed from democratic powers or at least the democratic organisations have their powers tempered.

- All grants must be only determined by departmental committees. Ministers and their officers should be banned from interfering. No more lists doing the rounds of ministerial offices

- Appointments for important positions similarly should be subject to processes which exclude political interference. There will be exceptions to this rule but these must be strictly defined. Departmental heads must be appointed by ministers, but we ought to mandate some commitment to merit-based appointment devoid of partisan favouritism. Let’s entrench the tradition of a politically neutral public service

- All infrastructure must pass muster with the federal or state infrastructure body or both. We suggest both as all significant investment requires state and federal funding. For example, the biggest infrastructure suggestion of the day, the Victorian Suburban Rail Loop is yet to fully pass such scrutiny and is now a political football. This is the wrong outcome for such massive expenditure. No politician has the expertise to make an informed decision

There are many other wise attributes of the SOP Doctrine. We only have to look at the social chaos in the US now caused by the infection of the Judiciary in the Supreme Court by the Executive arm.

There are strong arguments in the three issues above where we need to rediscover the SOP Doctrine and use it to cleanse our polity of its current malaise where inefficient corruption is seen as normal.

Dick Gross is a lawyer, company director and former Mayor of the City of Port Phillip. He is deputy chair of Keep Australia Beautiful Victoria and is a Fellow at the University of Melbourne.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.