We are now familiar with artificial intelligence as meaning intelligence demonstrated by machines as opposed to that demonstrated by animals, especially humans. The adjective ‘artificial’ however includes ‘fake’ among its synonyms.

We pose the proposition that the Coalition government’s commitment to artificial intelligence in its digital economy strategy is a demonstration of its fake intelligence.

Your humble columnist has written in the past on the topic of the Morrison government’s 2021 Digital Economy Strategy. In that column I laid out the wasted years of digital economy progress under Abbott-Turnbull-Morrison.

The ultimate failure of a decade of digital economy strategising was noted by comparing the objectives of the Coalition strategy in 2021 (For Australia to be a leading digital economy and society by 2030) with Labor’s 2011 goal (that by 2020 Australia will be among the world’s leading digital economies.)

The intervening decade was marked by there being no Minister for the Digital Economy under Abbott, a squib of a document in 2016, and a slightly more solid attempt as Australia’s Tech Future in 2018.

For the 2022 election the Liberal Party has released what they call Our Plan for Growing the Data and Digital Economy. The policy states:

“We have already invested over $3.5 billion in digital initiatives since 2020, from building the digital and cyber workforce to enhancing Australia’s capabilities in artificial intelligence and quantum technologies.”

This claim is also made in the 2022 update to its Digital Economy Strategy, which includes a break-up of the amounts as:

- $1.2 billion for the Digital Economy Strategy in the 2021–22 Budget to ‘unlock the value of data, drive investment and uptake of emerging technologies, build the skills required for a modern economy, and enhance government service delivery’

- $800 million previously announced Digital Business Plan included in the 2021-22 Budget.

- a further $347 million added added in 21-22 MYEFO to bolster the government’s digital economy investment.

- $1.1 billion in the 2022-23 budget to support the development of Australia’s leading digital economy.

This reveals a common error in the way the Coalition speaks about its strategies and plans. They regularly confuse commitments to forward expenditure with the idea that they have already invested these funds.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is one component of the strategy, and the government separately detailed it as Australia’s Artificial Intelligence Action Plan. This reiterated the AI spending commitments the Digital Economy Strategy:

- $53.8m – Establishing a National AI Centre and AI and Digital Capability Centres

- $33.7m – AI-based solutions to solve national challenges grants

- $12m – Catalysing AI in our regions grants

- $24.7m – Next Generation AI Graduates Program

- $0m – Artificial Intelligence (AI) Action Plan

The National Artificial Intelligence Centre has already opened. Its website links to a CSIRO post that claims:

“Australia, like many other advanced economies around the world, is currently facing economic growth challenges related to an ageing population and low growth in productivity.

“By creating the potential for industry to make better products, and deliver better services that are faster, cheaper and more safe, AI represents a significant opportunity to mitigate these challenges by boosting productivity in Australia, enhancing our national economy, and unlocking new societal and environmental value.”

The Coalition’s commitment to AI is so significant that the AI Action Plan was a core element of The Action Plan for Critical Technologies released in November last year. Not to be left out the ALP has announced a $1 billion Critical Technologies Fund to be set up within its $15 billion National Reconstruction Fund.

As reported here Labor says “the application of technology like AI improves the way that businesses operate and is supercharging whole economies. It is why other countries had developed their own national AI investment strategies while Australia had lagged behind.” It is unspecified how much of Labor’s $1 billion will go to AI.

Labor is right to note that other countries are investing in AI strategies. That is the topic of a new paper by two QUT academics and their colleagues, Interpreting national artificial intelligence plans: A screening approach for aspirations and reality.

The study aims to determine the difference between the aspirations and reality of AI implementation among the countries that have released national AI plans. They use the screening component of signaling theory. The signals the study uses are the resources required to successfully execute an AI strategy.

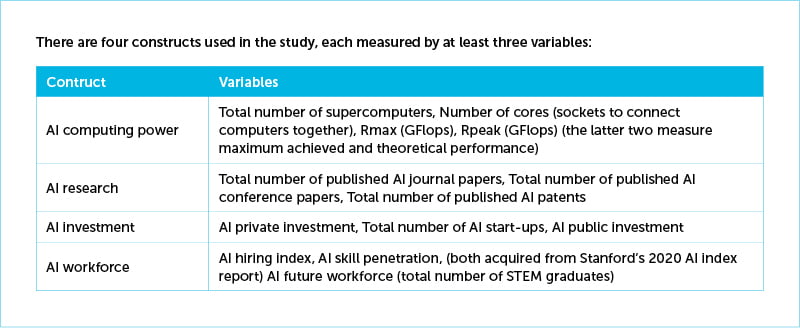

There are four constructs used in the study, each measured by at least three variables:

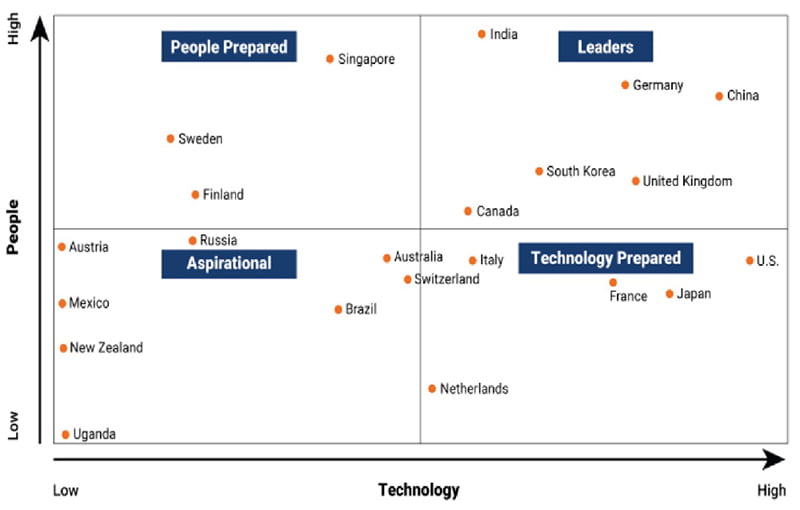

After converting these into two measures of People and Technology, the 50 countries with AI strategies could be mapped on a two-dimensional map. The four quadrants were given titles of Leaders, People Prepared, Technology Prepared and Aspirational. A subset of the countries is shown in the chart below.

The subset includes all the countries in the People Prepared and Leaders categories, five of the 14 countries rated as Technology Prepared, and only seven of the 27 countries rated aspirational.

Source: Fatima, S, Desouza, KC, Dawson, GS & Denford, JS 2022, ‘Interpreting national artificial intelligence plans: A screening approach for aspirations and reality’, Economic Analysis and Policy (in press).

Australia, unsurprisingly, fell into the Aspirational group. It is not all bad news though since it falls into the upper right corner of that quadrant.

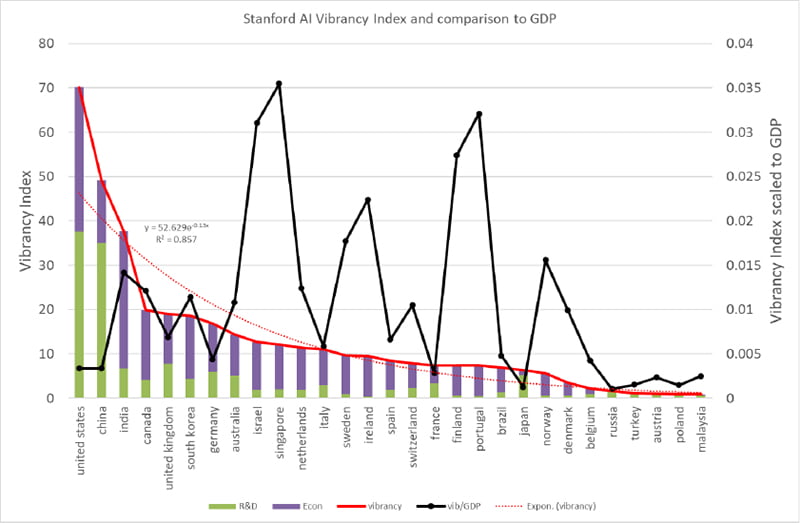

It is worth also noting the results of the Stanford AI Index which is referred to in the table as the source of two variables used in the screening analysis.

The Stanford approach reports an AI Vibrancy Ranking for only 29 countries, which is composed of two measures, R&D and Economy, that are presented graphically as two columns and ranked on the sum of the two (see note).

The six countries ranked Leaders in the screening approach plus the US wind up being ranked above Australia. The bad news is we are eighth in a list that declines exponentially at about 13 per cent per rank, which is shown in the trend line.

The larger the economy the more likely it is that a nation will be producing academic articles, patents and having new AI investments, so we shouldn’t be surprised about the leadership positions of the US and China. To get a better sense the AI Vibrancy index was divided by GDP in $US in 2020 (using World Bank data).

This takes away the leadership position and suggests that Australia’s modest commitment puts us into a new middle ranking position in an order which is led by Singapore, Israel, Portugal, Finland, Ireland and Sweden.

Both sets of data and both ways of looking at the data indicate that Australia does have a realistic ambition for leadership in AI, but that more is required. We only have a few days before an election will provide us with clarity about our immediate future.

Whatever the outcome we will have a government with a level of commitment to AI, but whichever it is has more to do to convert a favourable starting position into a truly leading one.

Note: The Stanford Vibrancy Index is actually the average of the measures of R&D and Economy, so for the chart we plotted half of these components so they would add to the index.

David Havyatt is a former telco executive, former adviser to Federal Labor Ministers and advocate on behalf of energy consumers. He is a long term observer of Australian innovation policy.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.