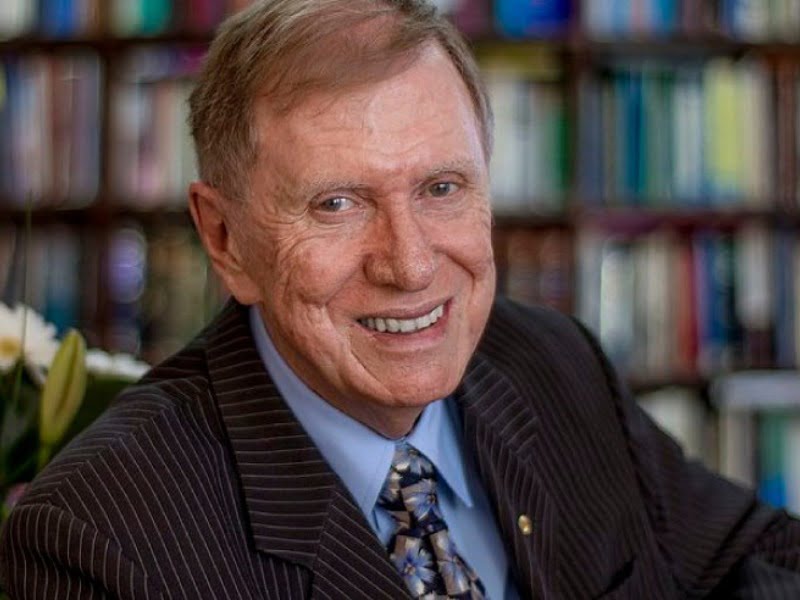

Former High Court Justice Michael Kirby recalls the one privacy principle he helped develop at the OECD in the late 1970s that was made redundant when Google emerged in 1998.

Speaking at the launch of the Australian Society for Computers & Law, the society’s high profile patron Justice Kirby laid out why Australia and the world needs to fight for citizens’ privacy rights and ensure governments of today and the future keep pace with advances in technology.

Unfortunately, according to Justice Kirby, Australia has failed to update its privacy laws to suit today’s technology and is sorely lagging behind today’s gold standard in the field — Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation, which came into force in May 2018.

It’s a shame, given Australia’s and Justice Kirby’s role in shaping privacy principles that would become law in multiple democratic nations.

In 1978 to 1980, as then chairman of the Australian Law Reform Commission, Justice Kirby was sent to Paris to chair an OECD expert group that was tasked with developing guidelines on privacy protection in the context of trans-border data flows. It was an early attempt at regulating computers before the Internet would go mainstream.

In 1980 — five years before Microsoft released Windows 1.0, nine years before Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web, and nearly two decades before Google — the Council of the OECD adopted the expert group’s privacy principles.

“Those guidelines have proved very influential, not only in Australia where they formed the foundation of the Australian Privacy Principles in the Privacy Act of 1988, but also in many other countries with different legal systems,” said Justice Kirby.

“The OECD privacy guidelines were extremely influential in the basic conceptual principles that would guide the international community at the outset of trying to devise … principles that would govern the regulation of computers and the protection of basic human rights, including the right to privacy.”

Despite the success of the OECD’s privacy guidelines, Justice Kirby said there was a “fundamental problem” with one of the core principles.

“That was a principle that governed the control by the individual or by society in the use that would be made of data that would be collected,” he said.

The expert group determined that data collected should only be used for the purposes for which they’d been collected, known to and approved by the data subject or as provided by law.

“The problem with that principle, which was fair enough at the time that it was adopted by the expert group, was that along came the search engines — Google, Yahoo and others — and those engines could use data and search data most efficiently for purposes other than that the data subject had consented to and knew about, or other than those that had been specifically provided by law,” he said.

“And therefore, one of the core principles of the OECD guidelines was not really appropriate to the technology as it developed.”

Technology from Google and other tech giants flummoxed the community of scholars and officials at the time. They also failed to devise new principles in response to emerging technology.

“Unfortunately, in the meetings that were held in the OECD and outside it became very difficult to agree on any change to the guidelines of 1980,” recalled Justice Kirby.

Today, privacy laws are being upended once again by artificial intelligence and, in particular, facial recognition technology developed by commercial outfits and used by law enforcement and government agencies for mass surveillance.

According to Justice Kirby, advances in technology that threaten individual rights to privacy and fundamental human rights are precisely why the Australian Society of Computers and Law is necessary.

“The technology continues to change and that technology requires the best minds to address the social issues and to lay out the principles that will guide democratic legislatures and the executive governments. The Australian Society of Community and Law will provide a voice for the international community and for Australia on these issues,” he said.

Justice Kirby highlighted the dangers of technology, surveillance and capitalism by contrasting what’s happened in democratic nations since 2000 to North Korean citizens’ lack of access to the Internet. He was chair of a 2014 United Nations report into human rights abuses carried out by the North Korean regime.

“I found in my work on North Korea that there is one country where citizens, except those in the elite, cannot get access to the Internet, and you realize in such a country the limitations that that imposes,” he said.

“But, on the other hand, the developments since the year 2000 have illustrated the way in which surveillance, technology and marketing have come together to have an enormous impact upon the freedoms of the individual.

“That has required a response by society to take away the capacity of capitalism to predict the decisions of individuals and propensities of individuals so as to trap them in a course that may not be in their interest and that they may not want if they were informed.”

The COVID-19 pandemic and the Australian Government’s COVIDSafe smartphone app to assist contact tracers offered a lesson closer to home as to why critical voices are a necessary counterbalance to new technology and hastily implemented policies and law.

“In Australia, the COVID Safe app was developed and was released two weeks before a piece of legislation was enacted within a space of two days by the Australian Parliament on the 14th of May 2020,” he said.

Within days of the app’s release, it had been installed by over 5 million Australian citizens or about a quarter of the population.

Yet, as Justice Kirby pointed out, in the space of one month only one extra case was revealed by the technology.

“Looking back, it does seem that the hopes or expectations that there would be an enormous value in the technology have not really been borne out,” he said.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.